For many British Columbians, the start of the 2010s was nothing but blue skies, red mittens, and gold medals.

The Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics put the city and region in the global spotlight, at a price tag in the billions, and many Vancouverites took to the streets to revel in national pride and enjoy the unseasonably warm weather.

From there, a series of bigger — and in some cases, darker — issues commanded our attention. Real estate, opioids, and organized crime dominated public conversations. As the decade wore on, links connecting many of those topics began to emerge.

As the 2010s come to a close, here is a look back at the some at the biggest stories of the last 10 years.

Real estate

No story affected British Columbians more than the surge in housing prices. From dinner party conversations to policy discussions in Victoria and Ottawa, everyone seemed to be talking about B.C.’s white-hot real estate market during the 2010s.

After house prices took a hit from the Great Recession, they began picking up steam in earnest in the early 2010s and have only recently begun to level off — a phenomenon most keenly felt in Metro Vancouver.

That region saw prices peak in 2016 and 2017, when the median price of a detached home topped out at about $1.8 million. Condo prices took a little longer to catch up but have also hit historic highs.

But it wasn’t just Metro Vancouver. As prices there climbed, British Columbians began to drive a real estate boom in many other B.C. regions.

Concern over skyrocketing prices prompted investigations into the role of foreign buyers, money laundering, and unethical real estate practices, along with a slew of government initiatives including a foreign buyers’ tax, provincial speculation tax, Vancouver empty homes tax and a federal mortgage stress test designed to cool the market down.

Those initiatives have seen prices level off somewhat (the median price of a detached home in Metro Vancouver now lies at “just” $1.57 million), but analysts predict the market will begin to pick up again in 2020 and 2021.

WATCH: Coverage of B.C. real estate boom on Globalnews.ca

Opioid crisis

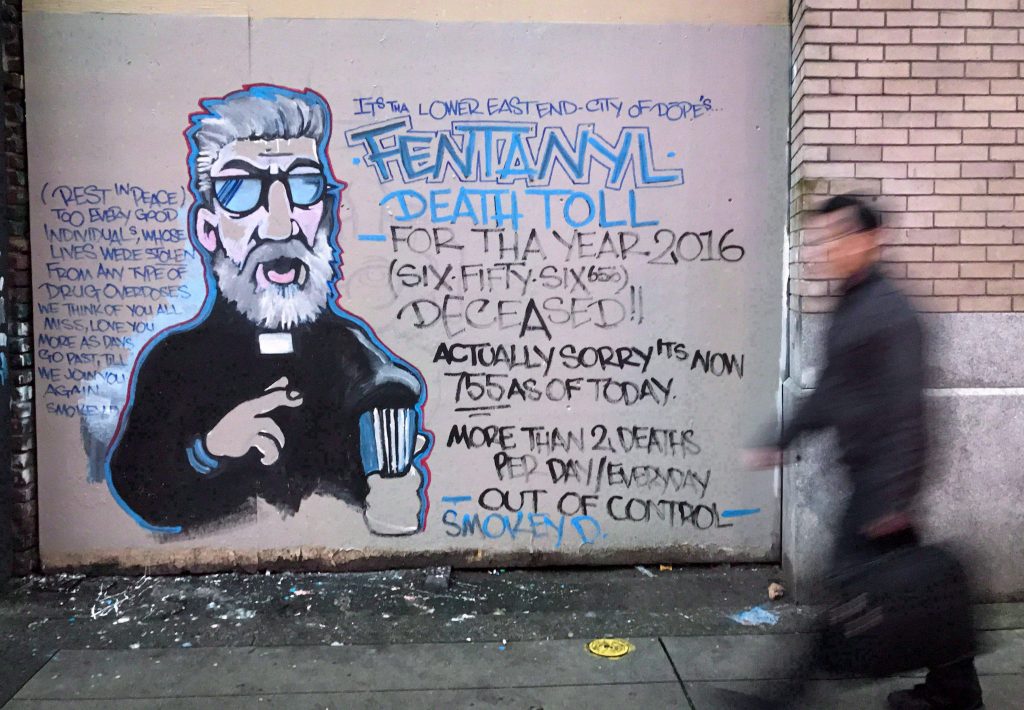

Looking back at the decade, the numbers are staggering. According to the BC Coroners Service, 6,856 people died of a drug overdose between January 2010 and October 2019. Tens of thousands more managed to survive an overdose, and many of those have survived multiple close calls from using illicit drugs.

With the rise of fentanyl and carfentanil in street-level drug supplies, health officials and advocates tried to take action in the first half of the decade: opening supervised drug sites, attempting safe drug supplies, and promoting cannabis as an addiction treatment.

Still, the numbers continued to climb. In April 2016 — when the death toll was already closing in on 2,500 — the province declared a public health emergency for the first time in B.C. history.

While more resources poured into prevention measures and research, hundreds kept dying each year, reaching a peak in 2018 with roughly 1,500 deaths. Advocates in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside said drug suppliers were finding new strains of fentanyl faster than they could be caught. And in small communities, the percentage of drug deaths compared to the population was among the highest in the country.

Researchers and health officials say the next step is to reduce the stigma of drug addiction through decriminalization, pointing out a majority of deaths happen alone and in residences. Municipalities have warmed to the idea, even though the prime minister has held firm that he won’t make that move.

With 2019 finally appearing to see a decrease in the death toll, solutions appear to be working. But the next decade will show whether the crisis is ever truly solved.

WATCH: Coverage of the opioid crisis on Globalnews.ca

Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympic Games

If there is a single moment of the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics that has stuck in the minds of Canadians over the last 10 years, it is likely the sight of Sidney Crosby taking a pass from Jarome Iginla and slipping the puck between the legs of U.S. goaltender Ryan Miller to give Canada a men’s hockey gold medal on home soil.

“It’s hard to write a better script than that,” former Vancouver Canucks and Team Canada goaltender Roberto Luongo said of Canada’s 3-2 overtime win.

The moment, which remains the most-watched televised event in Canadian history, capped a Games that many Vancouverites now view with nostalgia.

The Games started with tragedy with the death of Georgian luger Nodar Kumaritashvili. The Guardian UK wasted no time in saying the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics were shaping up to be “the worst Games ever.”

The city eventually let loose and revelled in Canada’s 14 gold medals.

A decade later, the legacy of the Games is still a subject of debate. One estimate had the Games costing $7.7 billion, although VANOC CEO John Furlong argued that number was inflated and actual cost was closer to $4 billion.

Even Vancouverites who preferred going to yoga to watching Crosby’s golden goal felt the impact of the Games. Large-scale projects linked to the Games — like Olympic Village, Vancouver Convention Centre, Richmond Oval, Canada Line, Hillcrest Community Centre and the improved Sea-To-Sky Highway — have left an indelible mark on the region.

A 2014 study from the University of British Columbia, however, found the Games did little to boost tourism but did note that the Games provided an added boost of national pride.

Nearly 10 years later, the legacy of the Games remains hard to measure. For many, that sense of national pride has transformed into nostalgia for a two-week period where the city celebrated in the streets and changed the narrative around its reputation as “No Fun City.”

WATCH: Coverage of the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics on Globalnews.ca

Stanley Cup riot

The good feelings and sense of community from the Winter Olympics appeared to spill over to 2011 as huge crowds gathered in the downtown core to take in the Vancouver Canucks’ run to the Stanley Cup final.

After several post-season failures, the Canucks, led by Daniel and Henrik Sedin, appeared to be a team of destiny. Defeating longtime rivals the Chicago Blackhawks in the first round, then Nashville Predators and San Jose Sharks, the Canucks advanced to the Stanley Cup finals for just the third time in franchise history.

With each win, crowds in downtown continued to grow to watch the game on a massive screen not far from Rogers Arena. On June 15, 2011, the largest crowd of all watched the series-deciding Game 7, which saw the Canucks lose 4-0 to the Boston Bruins.

The five-hour riot that followed was devastating.

Businesses and civilians suffered losses estimated at $2.7 million and $540,000, respectively, while the cost to the City of Vancouver, B.C. Ambulance Service and St. Paul’s Hospital was $525,000.

According to a B.C. government report, 112 businesses and 122 vehicles were damaged, and 52 assaults were reported against civilians, police, and emergency personnel.

- Three B.C. men fined, banned from hunting after killing pregnant deer

- B.C. child-killer’s attempt to keep new identity secret draws widespread outrage

- Inquest hears B.C. hostage was lying on her captor before fatal shooting

- ‘We’ve had to make a 180’: What Oregonians say they got wrong with decriminalization

The riot seemed like an eerie replay of the mayhem following the Canucks’ last Game 7 loss at the Stanley Cup Finals. What differed from the 1994 riot is that people held up their cellphones to record the mayhem. As rioters wreaked havoc, bystanders captured it all, sharing footage on social media.

Much of that cellphone footage became evidence.

The provincial report said 912 charges were laid against 300 alleged rioters: 264 adults and 54 youths. Of the accused, 284 pleaded guilty, 10 chose to go to trial (nine were convicted), and the Crown entered a stay of proceedings against six. Persecutions connected to the riot lasted five years and cost nearly $5 million.

Just as the Olympics had given the region an injection of civic pride, the Stanley Cup riots left the city with a black eye.

WATCH: Coverage of the Stanley Cup riots on Globalnews.ca

B.C. wildfires

British Columbia dodged a bullet in 2019 on the wildfire front, but the breather came after two consecutive years of intense, record-breaking fires.

In 2017, more than 1,300 fires consumed more than 1.2 million hectares of wildlands, costing the province about $564 million. The fire prompted a record-setting 10-week state of emergency, and at one point forced the evacuation of about 10,000 people from Williams Lake. Over the entire season, an estimated 65,000 people were displaced from their homes.

The following year proved to be another record-setter, as more than 2,050 fires consumed more than 1.3 million hectares, forcing about 5,300 people from their homes and prompting a three-week state of emergency at an estimated cost of $455 million.

At one point, B.C. Wildfire Service crews were fighting more than 50 massive “wildfires of note” at once, many in remote areas.

Both years saw wildfire smoke billow across the province, with the air quality health index topping out over 10 (meaning very hazardous) for days on end in many communities, with near-blackout conditions in Prince George at one point.

Residents were urged to stay indoors and public health officials counselled people to find refuge in malls and swimming pools.

The next worst fire season for territory burned was all the way back in 1958, with 855,000 hectares, while the previous most expensive was $182 million in 2009.

The fires prompted B.C. to review its emergency management practices and wildfire funding, and have raised new concerns about the effects of climate change.

WATCH: Coverage of B.C. wildfires on Globalnews.ca

2017 provincial election

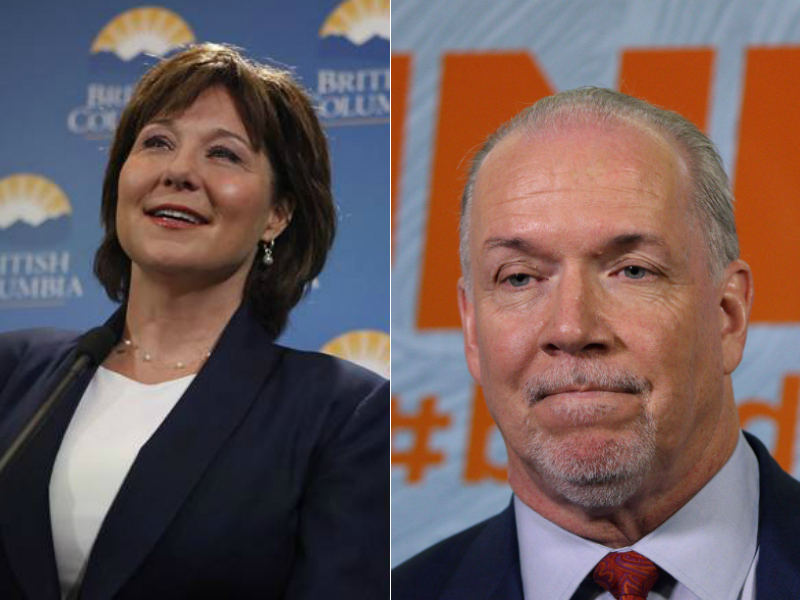

It was a political dynasty spanning nearly two decades — Gordon Campbell was elected as B.C. premier in 2001 and then Christy Clark took the helm starting in 2011.

But in 2017, 16 years of BC Liberal rule in British Columbia came to a dramatic halt. Clark led her party into the election and came out of it with 43 seats, one short of a majority, in the closest election in over a century.

The Liberals’ 43 seats were enough for Clark to form government — but not enough to win a confidence vote.

In June, more than a month after British Columbians voted, the NDP and Greens voted against the government. Their 44 votes were enough for government to be stalled and for Clark to pay a visit to Lieutenant Governor Judith Guichon.

Clark then resigned and asked Guichon to call another election. Instead, Guichon invited NDP leader John Horgan to Government House and asked him to form government with the support of the Greens.

Less than a month later, Horgan was officially sworn in as premier and the Liberal dynasty was over.

WATCH: Coverage of 2017 B.C. election on Globalnews.ca

Trans Mountain pipeline

The decade’s defining environmental debate began in 2013, when Kinder Morgan filed its application to expand the existing Trans Mountain pipeline from the Alberta oilpatch to the Lower Mainland.

After the federal government approved the project in 2016, the fight spilled into the courts and into the streets. Legal challenges were filed by B.C. First Nations and municipalities, arguing they hadn’t been fully consulted. Protesters gathered outside the Kinder Morgan terminal on Burnaby Mountain daily, leading to dozens of arrests.

The fight reached a fever pitch in 2018, after the new B.C. NDP government proposed a restriction on the flow of bitumen into the province until environmental concerns were addressed. That raised the ire of the Alberta government, which boycotted shipments of B.C. wine in protest and introduced legislation threatening to cut off gas supply to their western neighbour.

It all got to be too much for Kinder Morgan, which pulled out of the project — forcing the Canadian government to buy it to the tune of $4.5 billion. Taxpayer anger only grew after the courts overturned the project’s approval, forcing the government to go back to First Nations groups for further consulting. The project was approved for a second time in 2019, sparking a new wave of lawsuits.

All throughout, the federal and Alberta governments have reminded people of the positives of the pipeline expansion: more oil to market through a safer method than by rail, creating jobs and high economic returns. But protesters have argued that Canada should be investing more in clean technologies and cutting its ties to oil and gas.

The debate is sure to continue well into the next decade.

WATCH: Coverage of the Trans Mountain pipeline on Globalnews.ca

Gang violence

Several high-profile gang conflicts spilled over from the last decade into this one, with one death after another linked to well-known crime groups like the Bacon brothers and the Red Scorpions.

In 2011, Jonathan Bacon died in a gangland-style shooting in downtown Kelowna. Three people ended up pleading guilty to the shooting.

Much of the ensuing violence was centred south of the Fraser River, with neighbourhoods throughout Surrey, Langley and Abbotsford seeing spikes in targeted shootings, car chases and bodies found in burning vehicles.

In 2015, police in Surrey and Delta dealt with a series of shootings they said were linked to low-level drug trafficking.

But it wasn’t just gangsters and drug dealers being murdered — there were also innocent bystanders.

In 2018, Surrey father and hockey coach Paul Bennett was killed in his driveway in a case of mistaken identity. And in 2018, a 15-year-old Coquitlam boy was shot in the backseat of his parents’ car, caught in the crossfire between known criminals in Vancouver.

That last shooting prompted Vancouver Police Chief Adam Palmer to note a spike in gang violence not seen in 10 years, proving the problem was much more widespread.

Earlier this year, the federal government pledged millions of dollars to combat gang violence in B.C.

Concerns over safety and a lack of police resources later entered municipal politics, with Surrey’s new mayor and majority of council getting voted in on the promise to create a new civic police force. That rollout has gone less than smoothly, and the ensuing debate over how to police a city is proof that crime touches everyone, not just those in the lifestyle.

WATCH: Coverage of gang violence on Globalnews.ca

Northern B.C. murders and manhunt

B.C. was a hotbed for crime reporting in the 2010s, with shocking murder cases appearing annually. But few of those stories caught national and worldwide attention like the slaying of three people in northern B.C., and the ensuing cross-country manhunt for two young suspects.

It began with the discovery of the bodies of American Chynna Deese and her Australian boyfriend Lucas Fowler on the side of the Alaska Highway in July. When Vancouver botany lecturer Leonard Dyck turned up dead four days later — and Bryer Schmegelsky and Kam McLeod were reported missing — the already heightened interest in the case peaked.

The first bombshell in a story full of them dropped days after all three bodies were discovered: Schmegelsky and McLeod were still alive, and were wanted for murder. What followed was an all-hands-on-deck search that brought police, the media and even the military to northern Manitoba to try and find the suspects.

With RCMP across Canada combing through hundreds of tips and reported sightings, neighbourhoods were locked down and residents waited in fear, hoping the two fugitives would be caught. It didn’t turn out that way: Schmegelsky’s and McLeod’s bodies were found 23 days after their first victims were discovered.

As the decade draws to a close, this case sticks out for its randomness and lack of motive. The families of both the victims and families are instead left wondering why, with no suspects left alive to provide an answer.

WATCH: Coverage of the northern B.C. murders on Globalnews.ca

Money laundering

Duffel bags of cash. Luxury cars in shipping containers. Sky-high real estate prices.

They are just a few of the signs of widespread money laundering in B.C.’s housing market, casinos and luxury car market.

For the entire decade there have been red flags of the proceeds of crime being laundered through the province. A Global News investigation detailed shocking links between Chinese gangs, street drugs like fentanyl, B.C. casinos and the province’s high-priced real estate market.

Authorities dubbed the movement of cash and drugs the “Vancouver Model.” For years, the BC Liberals were criticized for turning a blind eye to the flow of cash.

BC NDP Attorney General David Eby called the situation a “crisis” and tasked former RCMP deputy Peter German with investigating the situation.

In the end, the German report found more than $1 billion of money being laundered, a lack of support from the federal government and various loopholes making the province vulnerable. An expert panel looking into money laundering in B.C.’s real estate market found an estimated $5 billion in “dirty money” was laundered through the province’s housing market in 2018.

But the findings didn’t place blame. That will be for the public inquiry, which the provincial government called in 2019 after substantial public pressure.

WATCH: Coverage of money laundering on Globalnews.ca

Comments