Half a dozen doctors’ diagnoses didn’t do it: In the eyes of Ontario’s Workplace Safety and Insurance Board, Norman Traversy says, his mental trauma’s all in his head.

Traversy spent decades as a firefighter in Mississauga before a series of injuries – to his back, his leg, his mind – sidelined him.

Some of those injuries, he says, have been treated differently than others.

“I was called ‘walking wounded,’ ‘reject.’ …

“Which is why people aren’t getting treatment for it, because once you do this, they get rid of you.”

MENTAL ILLNESS: How do I find treatment, and what happens next?

Three years after a report on workplace PTSD, and almost a year after promising swift action during a provincial conference on the crisis, Ontario has yet to pass or even bring forward a promised bill recognizing the importance of ensuring people get recognition, coverage and treatment for mental illness.

Global News asked the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board about Traversy’s case but a spokesperson declined to comment, citing privacy issues. He has appealed their decision and filed unsuccessful complaints alleging harassment and discrimination on the part of his now-former employer and his union.

Spokesperson Tonya Johnson also declined to comment on proposed changes to the way the WSIB handles PTSD claims.

“It would not be appropriate for the WSIB to comment on legislative matters. The Ministry of Labour would be best positioned to respond to questions about this,” she wrote in an email.

READ MORE: 6 months, 23 first responder suicides

WATCH: Global News coverage of PTSD across Canada

Traversy’s now 60. He’s been diagnosed repeatedly with post-traumatic stress disorder.

But he says the WSIB doesn’t buy it: After being cross-examined on the details of his trauma, he says, he was told he actually suffers from “socioeconomic stress” and isn’t covered.

“I was gobsmacked.”

It’s more than a matter of principle. WSIB recognition is the difference between coverage, benefits, livelihood or a lack thereof.

IN HARM’S WAY: The PTSD crisis among Canada’s first responders

It might be less of an issue if Ontario’s public health coverage were more comprehensive. But psychotherapy is only covered if you get it from a psychiatrist — not psychologists or any other specialists.

“If you want specialized care from a psychologist, that’s not covered under OHIP,” said Donna Ferguson, a psychologist at the Work, Stress and Health program at Toronto’s Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

“When people don’t have access to WSIB, then they’re paying out of pocket.”

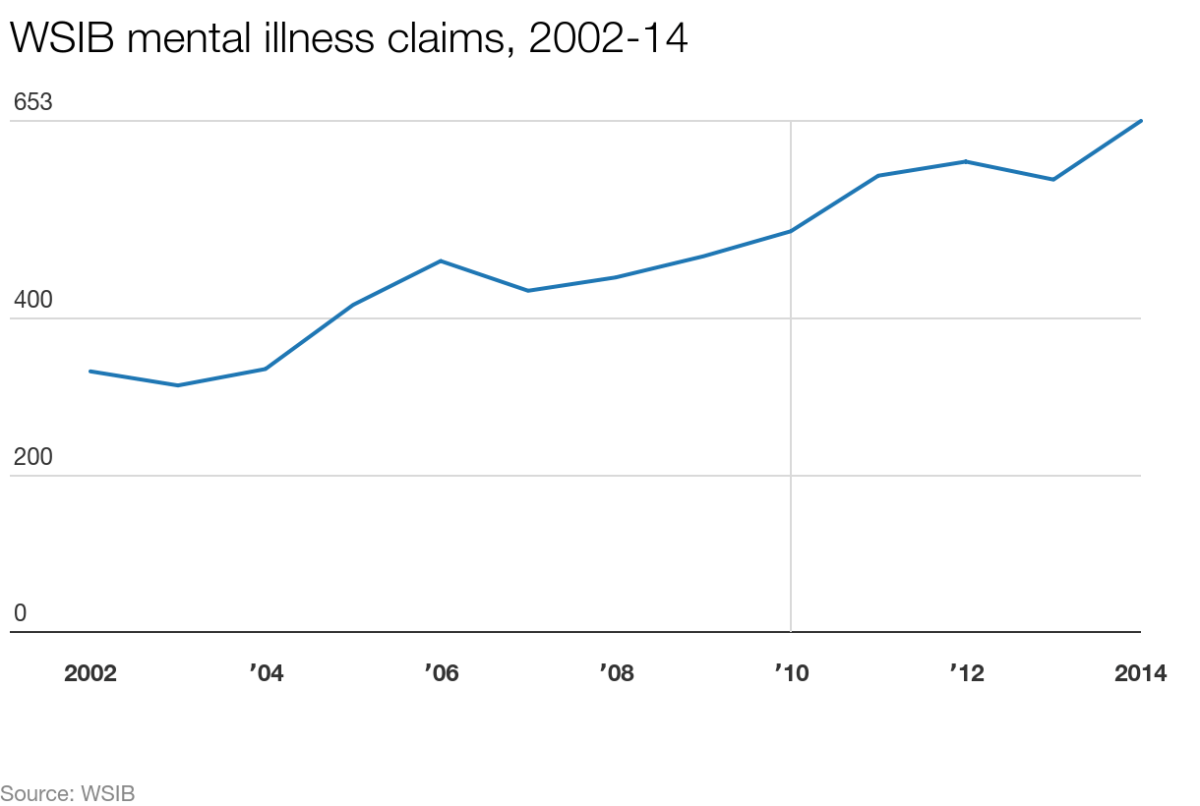

More Ontarians than ever before are filing disability claims for mental illness. Numbers obtained by Global News show that mental illness is one of the only categories of disease whose claims have risen in the past 12 years.

The number of allowed WSIB claims for “mental disorders or syndromes” almost doubled between 2002 and 2014, from 333 to 653.

In the meantime, the total number of injuries dropped by almost 80 per cent, from 95,572 in 2002 to 53,688 in 2014.

- Life in the forest: How Stanley Park’s longest resident survived a changing landscape

- ‘Love at first sight’: Snow leopard at Toronto Zoo pregnant for 1st time

- Buzz kill? Gen Z less interested in coffee than older Canadians, survey shows

- Carbon rebate labelling in bank deposits fuelling confusion, minister says

(The WSIB wouldn’t tell Global News how many claims have been rejected annually, by type of illness or injury. We’re still chasing that information.)

‘I was scared of appearing weak’: First responders speak out on PTSD

The Ontario government knows this is a problem. It’s known for years: NDP MPP Cheri DiNovo has spent years trying to pass a private member’s bill that would make PTSD a presumptive workplace injury for first responders — effectively giving people who’ve been diagnosed with the mental illness the benefit of the doubt in making their case.

Its latest incarnation, Bill 2, is still stalled at second reading.

“There’s literally nothing else I can do at this point,” DiNovo said.

“This is something that should have been dealt with years ago.”

Ontario Labour Minister Kevin Flynn says the government is working on a bill of its own — one that will be more “inclusive” than DiNovo’s and that will include provisions on preventing people from falling ill in the first place.

But his office has been promising action for years.

READ MORE: PTSD report, 24 months in the making, recommends PTSD conference

Last March, in the wake of a conference on PTSD and first responders’ mental illness, Flynn said he is “treating this issue very, very seriously.”

WATCH: (Fri, Feb 27) Two separate conferences in GTA discussing PTSD among first responders

DiNovo says he told her office they’d have something in November. November came and went.

Now, his office is saying early next year.

“We will bring forward steps early in the New Year,” Flynn said during Question Period on Nov. 25.

“In order for Ontario to be a leader in prevention, resiliency training and support for First Responders impacted by PTSD, we must do better than Bill 2.”

A spokesperson for Flynn’s office said “conversations are ongoing” about what exactly the bill will contain. It isn’t clear whether it will be specific to first responders or include more professions.

Every week or two, DiNovo says, her office gets a call from someone desperate and suffering and considering suicide.

It doesn’t have to be that way, she says.

“It’s a devastating illness but, I want to say, it’s something that can be treated. … You can get back to work.”

Global News’s award-nominated series on PTSD among first responders documented the burden on police officers, firefighters, paramedics and other first responders forced to face a debilitating disease alone, with inadequate or nonexistent support and frequently enduring the scorn or ridicule of their colleagues.

“Every delay costs lives,” DiNovo said. “This is unconscionable.”

It makes sense to give first responders the benefit of the doubt when they say their PTSD diagnoses are work-related for multiple reasons, Ferguson said.

“Obviously it would be easier for them if they felt they didn’t always have to go through this investigative process,” she said.

And Ferguson knows from experience how tough it can be to draw definite causal links for something as multifactorial as mental illness.

“There’s always other factors involved. A person is not a silo within the trauma of the workplace.”

That complexity can also make PTSD tougher to prevent. It’s important to include psychoeducation in training for something like policing, firefighting or paramedic work, she said, but “it won’t help everybody.”

Ferguson would like to see legislation like this start with first responders but expand to other professions that also experience repeated trauma.

“Whoever’s experiencing trauma at work should somehow have access to this,” she said. “You’d probably have to take it one profession at a time.”

But first responders are a good place to start, she said.

“The nature of their job is trauma. …

“Anything … that anyone can do to help people access care is a positive thing.”

Traversy knows what it’s like to be at the end of his rope. A coterie of cops were at his house a couple of weeks ago as he struggled with the desire to kill himself.

“I’ve buried three friends — colleagues, firefighters — inside of two years,” Traversy said.

All had killed themselves.

He’d rather not bury more of them.

Comments