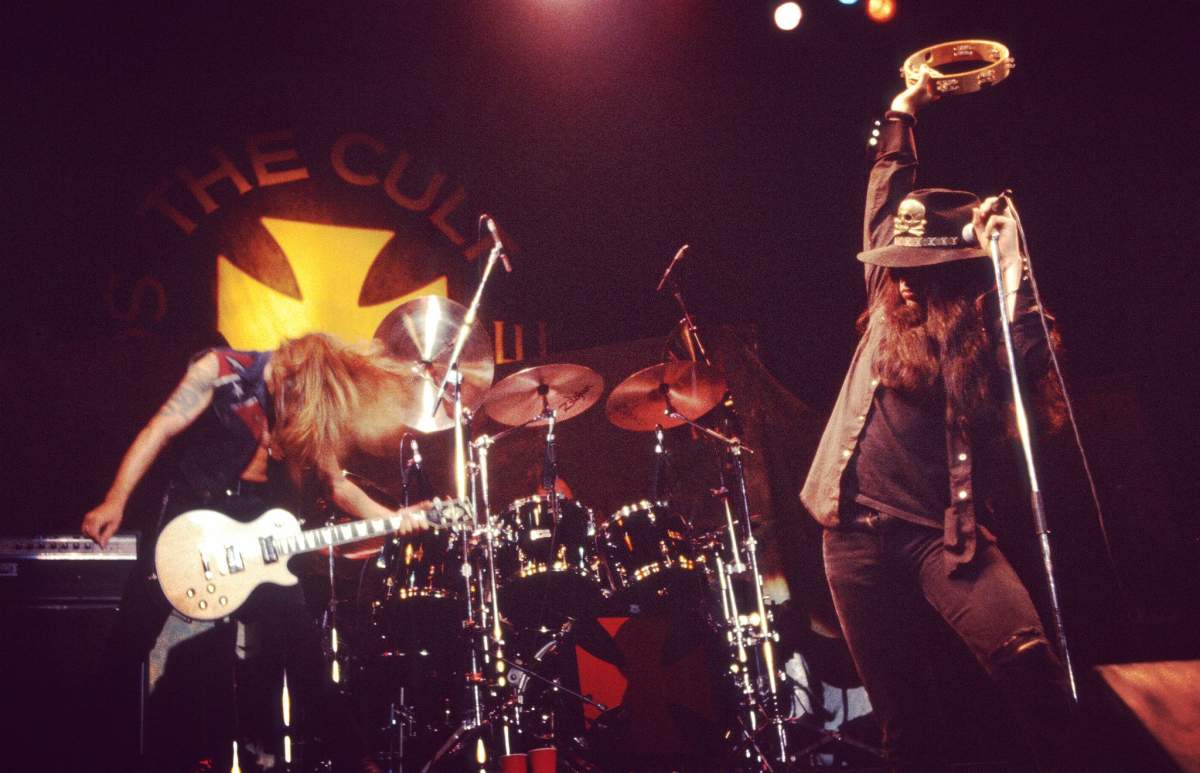

Ian Astbury is best known as frontman of the legendary hard rock/post-punk outfit The Cult, a band responsible for 1980 hits like She Sells Sanctuary, Love Removal Machine and Fire Woman.

The Yorkshire native is also the band’s primary songwriter, alongside co-founder and lead guitarist Billy Duffy.

The two formed the group under the moniker Death Cult and, since 1983, have been a driving force in shaping the modern rock and alternative scene, even after the band’s breakup and a second hiatus.

Although he was born in the U.K. to a Scottish mother and an English father, Astbury, 57, spent a majority of his childhood living in Hamilton, Ont., where he discovered the cultures and backgrounds of various tribes of Indigenous Peoples in southern Ontario — a topic consistently present in The Cult’s lyrics.

WATCH: ‘Fire Woman,’ the lead single from The Cult’s smash-hit 1989 record, ‘Sonic Temple’

Besides shaking the foundations of industry with The Cult, Astbury has pursued a solo career and made a guest appearance on a variety of musicians’ albums, including Debbie Harry of Blondie, Slash, Nine Inch Nails and Black Sabbath‘s Tony Iommi.

READ MORE: Liam Gallagher debuts new song ‘Shockwave’ live in London

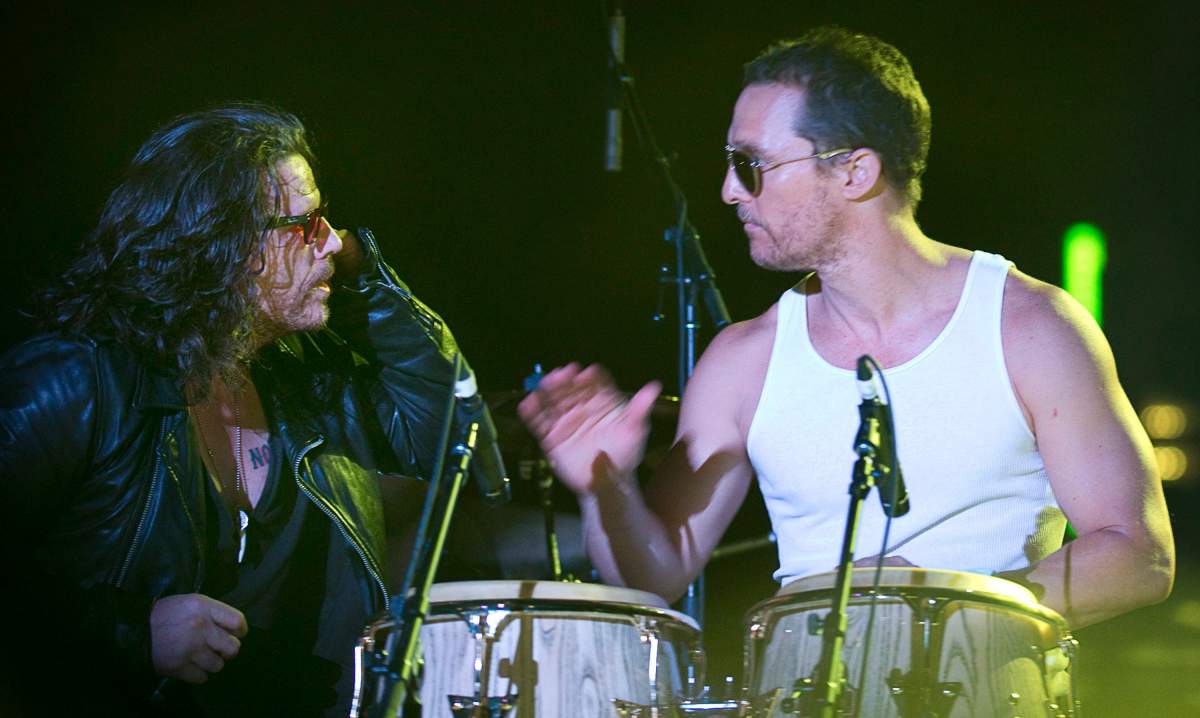

After completing the Canadian leg of the critically acclaimed A Sonic Temple tour last week — which celebrates the 30th anniversary of The Cult’s most commercially successful album, Sonic Temple (1989) — Astbury took the time to sit down with Global News.

From the history of struggles within The Cult to the commercial impact of Sonic Temple and how a visit to the Six Nations of the Grand River reserve became a formative moment in his childhood, Astbury didn’t hold back on sharing some insight into his life.

He also hinted that fans of The Cult may hear new music sooner than they think.

Global News: Not a lot of people know this, but you spent some years growing up in Hamilton, Ont., right?

Ian Astbury: Absolutely, yeah, that’s right.

So what was it like growing up in Canada for you?

I think it was the first time I felt like an outsider. Well… It wasn’t the first time because I experienced being an outsider in the U.K., too. My mother was Scottish and my father was English so we’d moved from Merseyside area to Glasgow and then, suddenly, I was labelled English. Because of that, I was ostracized; I was different. Then we went back from Scotland to England, and I was considered Scottish because of my slight Scottish accent so they always picked on me for that. I always found myself with the outsider kids: the kids with other cultural or racial backgrounds.

When I came to Canada, it didn’t matter. Kids were like, “You’re just an immigrant.” That was it. So all my mates were from Turkey, Jamaica, Pakistan, et cetera. There were some kids in our group that were the only Indigenous kids in our school, too, so that’s who I ran with. I remember being in a class one day, and this one Indigenous kid got up and walked out the class. I was blown away. He didn’t like what the teacher was teaching, and the teacher was like, “Come back!” His name was Lance. He just walked out of class, and I was like, “Wow, you can do that?” I was just tripping. This kid was totally cool about it; it just wasn’t a big deal to him…

I thought that was so cool, so I started hanging out with him and his brother. Then I found out that these guys had a completely different experience being raised in this anglicized culture so I really wanted to know more about their background. I quickly became fascinated with their culture, and that’s when I started to read up on it.

- Michael Jackson accused of child sex trafficking by 4 siblings in new lawsuit

- Robert De Niro recites Abraham Lincoln’s warning call for ‘civility’ at Carnegie Hall

- Cher’s son, Elijah Blue Allman, arrested for 2nd time in 3 days

- Justin Timberlake sues to block unseen bodycam footage from 2024 DWI arrest

READ MORE: Full lineup revealed for Canada Rocks with The Rolling Stones

Various Indigenous cultures have been a theme consistent in The Cult’s back catalogue. Was this your introduction to Indigenous cultures?

Pretty much, yeah. I remember going to the Six Nations of the Grand River reserve, and that’s where I had my first epiphanic experience. I got pretty bored with our tour guide so I wandered off on my own and came across all these Indigenous kids playing lacrosse. I was so mesmerized by them all running around. They weren’t at school, but we were. They were just running around playing, shirts off, having an amazing time. Another kid went by on a horse with no saddle, too. It was amazing. Then there was an old man sitting on a step. I immediately went and sat beside him. He was really cool with me. He was smiling at me, smoking a pipe, and I thought: “I feel really comfortable here. I really feel like I belong here.”

It was a really important experience to me, because that’s when I became immersed in Indigenous philosophy and the core of the culture. I really think that’s the key to everything.

Culture?

Exactly, yes. I truly think culture and learning is key to everything and I owe that mindset to the Indigenous Peoples. I honestly think they have a special knowledge and relationship about the Earth that those of us brought up in industrial lives or in society don’t even consider. We are part of the environment. Nature isn’t separate; we are part of all of it. That’s always been a belief of mine, and I’ve always tried to weave that into the narrative of the band.

Get breaking National news

In Indigenous culture and tradition, they acknowledge that so I’ve always thought we don’t need to be spending billions of dollars. The key is to actually sit down, listen and ask the Indigenous Peoples for help. It’s as simple as just saying: “We’re uneducated. Please educate us” or “Show us the right way.”

READ MORE: Brian Wilson postpones tour, says he feels ‘mentally insecure’

Sonic Temple seems to be one of The Cult’s most culturally inspired albums overall. What, exactly, inspired the artwork?

To me, in many ways, the guitar player, Billy, represents the masculine element, whereas the singer, me, represents a feminine element. When the two co-exist, there’s a harmony. There’s always the good “guitar hero,” which is why I’m in the background. I didn’t want to be front and centre because I was objectified so much by the way I looked. I didn’t want that. I prefer people experience the essence of what I was trying to do so it took on this mystique.

There’s some symbolism there that really works for me, too. Every time I look at it, I end up in a trance. I get transfixed and transposed into a different consciousness. We thought it had a certain energy to it. The colour palette wasn’t really something we’d seen on other album sleeves so it was very unique for its time. Now, it’s kind of passé, but then it was unique, and I think that’s one of the things that contributed to people wanting to discover what was behind it.

That’s right. Thank you! The word “tour” always conjures up something commercially contrived. In my mind, this is something a little bit more… this is what we’ve been doing for so long, it’s our life. When we go out on the road, it’s more like a nomadic expedition. I never think of it as a tour; I sometimes think of it as deployment. [Laughs]

Is there a reason why you’ve named this run of shows A Sonic Temple rather than just Sonic Temple?

We called it A Sonic Temple because we thought it was a good umbrella to look at the history of The Cult. It’s really all about celebrating the DNA of The Cult, not just Sonic Temple, but from the earlier Death Cult days through to Hidden City (2016).

Our music has oscillated; there have been so many different permutations of the band and a lot of responding to the times and environments that we were in and then reflecting that in our music. That was always the path for The Cult. It wasn’t necessarily to do something contrary to what everyone else was doing but just to do what we were into. We never really fit into a particular genre.

Back in the day, even MTV had trouble putting us in a specific category. They put us in 120 Minutes and Headbangers Ball. “Were they alternative or hard rock?” They really didn’t know where to put us so we straddled all of it. I think maybe it’s helped our longevity, but it’s been detrimental to the band’s potential commercial success. Which was a conscious choice I think I made after Sonic Temple came out.

READ MORE: Slash confirms new Guns N’ Roses music in the works

Commercially, Sonic Temple actually was The Cult’s most successful album, right?

Commercially, yes. It’s difficult to articulate. The label did an amazing job of marketing it as a rock record. But that’s not the way I perceived it. I perceived it as something so much more than that so it ran against convention and it did what it did; it sold. It went multi-platinum around the world. It did resonate with some people — I think maybe on a subconscious level — but I was trying to start a conversation. Then it was a case of, “OK, we tried a different angle,” and I don’t think it was really until we started getting into the last three albums that we picked up that thread. I just wanted to be in a situation where I could do something more artistically driven and less career driven.

When you’re inside of it, you don’t know the external machinations of the industry. You’re not privy to it because your point of contact — usually your manager, A&R guy, producer or friends — start making suggestions, and then when you step outside, you think, “Wow, we should be doing this, this, this and this instead,” and I was always the one that was going outside and saying, “Wait a minute, this isn’t entirely correct.” But I think at that point, there was just such velocity in terms of the band’s success. It was meteoric.

You haven’t played some of these Sonic Temple songs in a long time. Does playing them bring back any of those memories?

Yeah, Soul Asylum we haven’t played for 30 years, which I always thought was kind of soft and lyrically sophomoric. But then I go back to it and think that there was an emotional intelligence there… that it was quite deep. We last played it in ’89, and now we’re playing it every night. Same with American Horse.

Are you guys changing the set every night of the tour then, or is there a set flow for these shows?

A little bit… more in the encore section. When you build a setlist, there’s a certain chemistry and set narrative. Only certain songs will work in certain positions, and it takes a minute to get that right. But once you get it dialled in, there’s an arc to the set, then you can coordinate your production and all that kind of stuff with it as well. The more spontaneous stuff happens in the encores. We’ll walk out onstage, Billy might go like, “Are we gonna do Saints Are Down tonight?” and I’m like, “No, we’re playing Wild Flower.” The energy of the room might dictate something celebratory, and we never want to take the mood down.

READ MORE: Plug gets pulled on Neil Young at festival, but he keeps on rockin’

Well, when we first met, we were living in his flat in Brixton; I’d sleep on the couch. [Laughs] So yeah, you could say it’s very different. We spent a lot of time together and we were immersed in each other every day. We were always exchanging ideas but now we have very separate lives. We both have different lifestyles so when we do come together, we bring whatever it is that we’ve been musing on outside of that. Then we come into an intensive writing period. It’s a different way of writing as opposed to like a gradual thing when we were younger because as you get older, your life takes over. But we’ve been managed to maintain a relationship over 10 studio albums and three decades so it’s still there; there’s still a chemistry that works.

And before recording Sonic Temple in Vancouver, you and Billy moved to L.A. together, right?

Yeah, that’s right.

Judging from what you’ve said, it sounds like you were never actively seeking mainstream success, even though you had it very early on in the U.K. Was that initial success what drove you guys to the U.S.? Was there a desire to escape?

1987 was an intense year for us, too. We released Electric, we did a nearly sold-out 20-plus-date U.K. tour, came over to the U.S. to open for Billy Idol, played arenas — including Madison Square Garden — then went back to Europe and played with Iggy Pop, did a show with David Bowie, then went back to the States and did a tour with Guns n’ Roses, who opened for us, and then went right across Canada. By the end of those dates, we were absolutely exhausted. But it wasn’t just that year, it was the previous six, too. From like ’81 to ’87, it was just so intense, and there were no days off. Then one day, the management had gone to L.A. for a business trip, and they said: “Why don’t you join us? Come stay in this hotel with us.” So we went to stay for two weeks and we were like, “This is really chilled out,” because London was really intense.

I couldn’t walk down the street anymore. I would get so much hassle because of the way I looked. I had to tie my hair up all the time and I kind of dressed down when I would go out so I used to get a lot of negative attention: cab drivers shouting at you, being confronted in the street. I went out in a full mariachi suit one night. I was walking through Leicester Square and had a couple of skinheads cross me. It was pretty hairy, but I got out of it. It was just like, “This doesn’t feel right. It feels a little bit tense in London.” Because we’d gone out a lot and hit it really hard, but we just needed to put the brakes on for a second. We got to L.A., and all of a sudden, it just changed.

We got soaked up in this mythology of Los Angeles and what it really was. There was such a multicultural feel and diversity to Los Angeles that was really enticing. Sort of like how it was in Canada, too. I was like, “This is really cool.” When it came time for us to go back, we thought, “Let’s stay a little bit longer,” and next thing you know, we’re like, “Let’s move into these short-term apartments.” So we did.

READ MORE: Rolling Stones return ‘Bitter Sweet Symphony’ royalties, rights to Richard Ashcroft of The Verve

It definitely sounds like some of your most formative years were spent living in North America. I mean, you’re still here and writing incredible music, so I must ask, is there new music in the works?

There’s some songs and there’s been a few sessions. We’ve been doing some discovery. The initial period is where you go and see what’s laying around. I have a bad habit of putting everything on my cellphone so my voice memos are just packed with songs — about 250 ideas. That doesn’t mean they’re any good, but that’s just because there’s a lot of repetition.

WATCH: The Cult’s seminal 1985 hard hit, ‘She Sell’s Sanctuary’

—

As of this writing, it’s unclear when the band will release the followup to its 10th studio album, Hidden City. Later this year, the band plans to release a 30th-anniversary remastered edition of Sonic Temple through Beggars Banquet.

For more information on The Cult and A Sonic Temple shows, you can visit the band’s official website.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.