On June 12, Abdulmuti Mohamed Elmi was charged with shoplifting from an Ottawa LCBO store and assaulting a man with a liquor bottle, but the RCMP had more serious concerns about the 24-year-old.

An RCMP constable alleged in a court application that he had reasonable grounds to fear Elmi “may commit a terrorism offence” — namely leaving Canada to participate in a terrorist group.

The RCMP declined to comment on its terrorism concerns and Elmi’s lawyer did not respond to an interview request. But the case is the latest to mix crime and terrorism.

About a quarter of Canadians involved in terrorist activity have criminal histories, according to a declassified Canadian Security Intelligence Service report. They had “engaged in a wide spectrum of illicit activities,” most commonly low-level crimes and assaults.

Criminals are attracted to terrorism because it offers violence, status and adventure, the report said. They may also see it as way to atone or to reframe their actions “in a more positive light,” it added.

But the transition from crime to terrorism was not as prevalent in Canada as in Europe, it said.

As far back as the mid-90s, Al-Qaeda-linked extremists based in Montreal such as Ahmed Ressam, who later attempted to bomb Los Angeles airport, raised cash through petty thefts and frauds.

The criminal-terrorist link surfaced in Alberta as recently as May, when a judge approved the extradition of Abdullahi Ahmed Abdullahi, alleged by the U.S. to have held up an Edmonton jewelry store to bankroll the activities of associates fighting in Syria.

A Quebec teen was sentenced to three years in 2016 for robbing a convenience store at knifepoint to finance his attempt to join the so-called Islamic State. He told police he was allowed to steal from Canadians because they were “at war with Islam.”

Get daily National news

Elmi has not been charged with any terrorism offences. Instead, the RCMP has asked the Ontario court for a peace bond that would impose restrictions on him for up to a year. In similar cases, police have sought limits on the travel and internet use of terror suspects.

- Porter flight from Edmonton loses traction, slides off taxiway at Hamilton airport

- Trump keeps carveout under CUSMA in new 10 per cent global tariff

- Coffee-hockey combo — or breakfast beers? — for bleary-eyed Olympic fans

- Free room and board? 60% of Canadian parents to offer it during post-secondary

Ten days after the RCMP began the process of obtaining the terrorism peace bond, Elmi allegedly robbed an Ottawa convenience store while out on bail and was charged with four counts. He also faces two charges related to the alleged May 14 liquor store incident, two others for allegedly assaulting a man while robbing him on May 28 and one more for causing a disturbance by fighting.

Unlike in Europe, however, where criminals are said to be increasingly moving directly to terrorism, in Canada “the proportion and overall number of criminal mobilizers is not increasing, despite the growing criminal nature of extremist groups abroad and trend lines in European homegrown extremists,” CSIS wrote.

Canadians who had criminal pasts also “tended to mobilize slower than those who did not,” the report said. CSIS analysts said this was because their “criminal activities may distract focus” from their extremist pursuits, and their legal troubles get in the way of their plotting. Criminals may also be more cautious because of police attention.

Also, the “negative realities of criminality (drug addiction, financial hardships) might impact an individual’s capacity to plan or finance an intended mobilization pathway,” CSIS wrote.

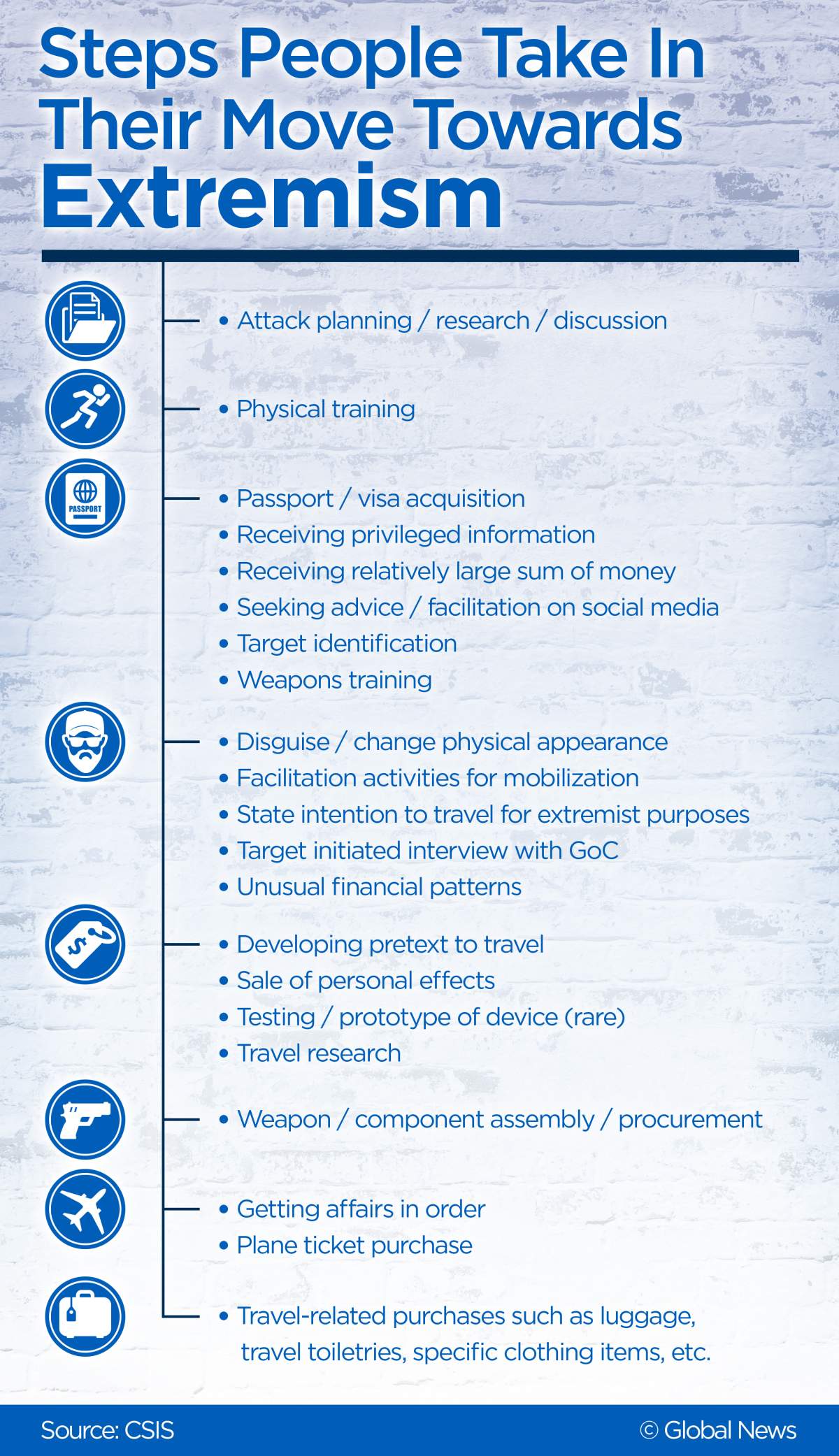

The report was part of a CSIS project that aimed to identify the steps taken by extremists as they “mobilized” either with the intention of conducting a terrorist attack or leaving Canada to join terrorist groups. The project was part of the CSIS response to the October 2014 terrorist attacks that killed two Canadian Forces members in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Que. and Ottawa.

A summary of the findings was posted on the CSIS website in February but documents containing more details about the project were released under the Access to Information Act to terrorism researcher Prof. Amarnath Aramasingam.

The documents provided additional information about how Canadians moved towards terrorism, a process they said took about a year. Only in 10 per cent of cases did extremists mobilize in five days or less, it said.

“The project found that mobilization to violence is rarely sudden or spontaneous. It is a process that requires careful planning and preparation, as well as a logical sequence of activities,” the documents said.

“This finding contradicts anecdotal evidence that mobilization can happen ‘out of the blue’ or ‘all of a sudden,’ or as reported by friends and family members, that there were no warning signs.”

Elmi appeared in court on July 12 on his terrorism peace bond, records show.

The RCMP has been using terrorism peace bonds as a fallback in investigations where they suspect someone has been involved in terrorist activity but they lack the evidence to lay criminal charges.

If the peace bond is approved by a judge, or if Elmi consents to it, the Orleans, Ont. resident would have to abide by a list of conditions that could include surrendering his passport and not communicating with specific extremists and groups.

“Peace bonds assist in managing the threat posed by an individual where the evidence is assessed as insufficient to achieve charge approval,” according to a November 2016 RCMP document obtained by Global News.

“They are a means of establishing some control over individuals short of a charge or conviction.”

But as the August 2016 attempted suicide bombing in Ontario by ISIS supporter Aaron Driver showed, peace bonds are not a guarantee.

“Peace bonds do not fully mitigate the risk posed by an individual,” the RCMP document acknowledged.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.