While the world seeks unity to fight COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, China and the U.S. have become involved in an ugly slagging match over the illness.

Beijing announced on Tuesday that it is expelling all China- and Hong Kong-based journalists from the New York Times, Washington Post and Wall Street Journal. It further demanded that those newspapers, as well as Voice of America and Time magazine, provide “detailed information ” about their work in China.

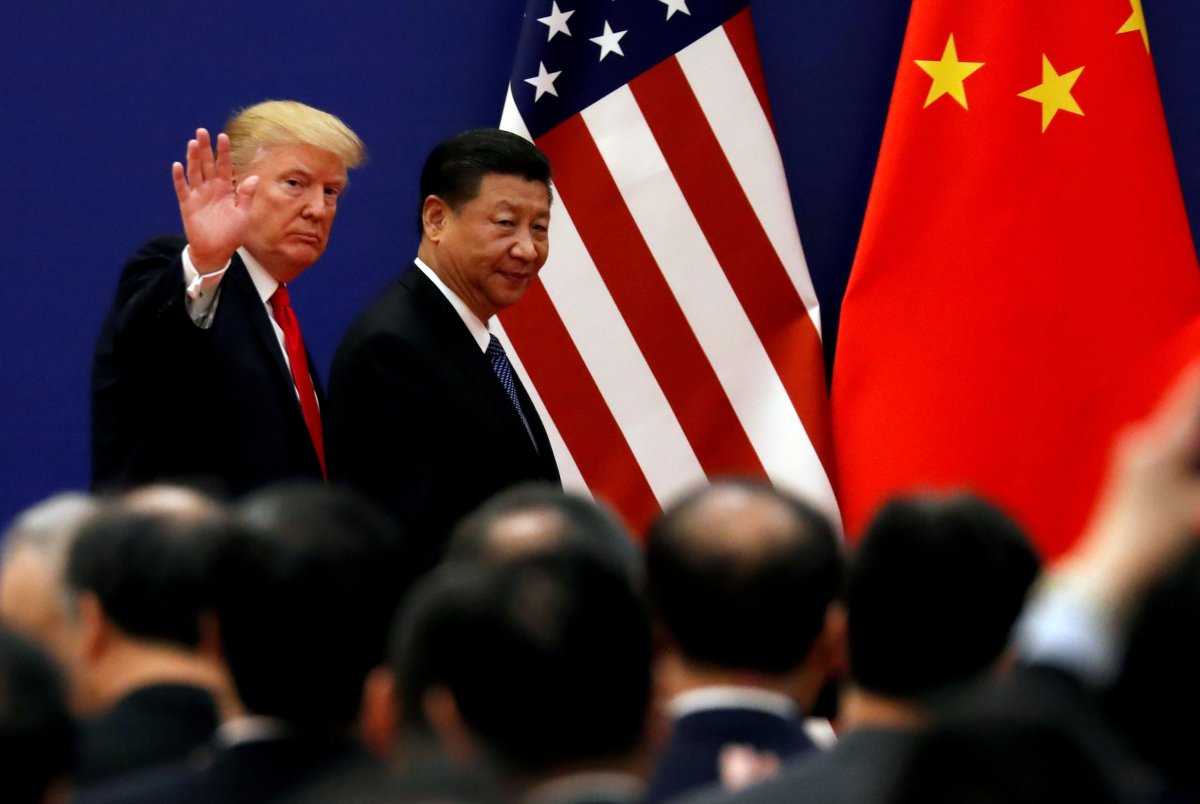

The deportation order came just hours after China denounced U.S. President Donald Trump for referring to COVID-19 as “the Chinese virus” in a tweet that a Communist Party newspaper immediately called “racist.” In what Foreign Policy magazine cited as an example of COVID-19 becoming a “geopolitical football,” Trump’s secretary of state, Mike Pompeo, publicly referred to it two weeks ago as “the Wuhan virus.”

Though it is hard to see a direct link between the deportation of journalists and the disease that the World Health Organization finally decided to call COVID-19, a Chinese academic was quoted Tuesday in official media as saying the tweet from the White House “appeared to be a tit-for-tat move in response to a decision earlier this month by U.S. President Donald Trump that five Chinese state media companies reduce to 100 the number of Chinese citizens they employ in the U.S.”

- Life in the forest: How Stanley Park’s longest resident survived a changing landscape

- ‘Love at first sight’: Snow leopard at Toronto Zoo pregnant for 1st time

- Carbon rebate labelling in bank deposits fuelling confusion, minister says

- Buzz kill? Gen Z less interested in coffee than older Canadians, survey shows

Only last Friday, the U.S. State Department summoned China’s ambassador to Washington to explain why his foreign ministry’s chief spokesman had publicly demanded an investigation into whether a U.S. military lab had created the new coronavirus and suggestions by other Chinese diplomats that U.S. troops had brought the highly infectious disease to China.

Also tumbling out there in the digital and electronic fog has been a conspiracy theory, perhaps first circulated by a U.S. senator, that the pathogen causing global hysteria got its start at the People’s Liberation Army biochemical weapons lab in Wuhan.

There is a preposterous Canadian angle, too: that the virus might have come from research allegedly stolen by Chinese scientists working at a lab in Winnipeg.

The rift between Beijing and Washington comes at a moment when the stark outlines of the terrible economic effects of this scourge are starting to become known. Production in China was down by about 13 per cent in January and February. Retail spending dropped by one-fifth. And the figures for March and April are unlikely to be any better.

The collapse is a portentous warning of the extreme challenges that lie ahead for Canada and other countries as they digest the economic consequences of the pandemic. Estimates circulated by some Canadian economists that the country’s growth rate will retract by two per cent in June already seem badly out of date.

Going forward, how much other economies will want to continue to depend on Chinese products and, in particular, Chinese parts is unknown.

However, no matter how much positive spin China puts on the strength of its official response to the new coronavirus, exports from China will continue to take a terrible hit. Canada, for one, may finally figure out that it is smarter to diversify trade, rather than be besotted by the trade prospects with only one country.

Spitballing about the economic fallout is easier than divining the truth about the origins of the disease, which is impossible now and probably always will be. But it is clear that at a time of intense international anxiety over COVID-19 — or whatever you choose to call it — relations between China and the U.S. are sour and getting worse. Both sides have begun using the pandemic to take clout each other.

On Tuesday, under the headline “Trump’s racist tweet another attempt to deflect blame,” the Chinese Communist Party’s Global Times denounced Trump’s “temerity” for calling COVID-19 “the Chinese virus” and said this had been done to mask the mistakes he had made in organizing the American fight against the disease.

”Labelling a virus to reference to a country, region or people contradicts long-held principles of the World Health Organization (WHO),” the daily wrote.

“What prompted Trump to utter such reckless words? What are the likely consequences and fallout of his remarks?”

The WHO has badly damaged its credibility by refusing to attach any blame to China for keeping news of the virus secret from its own citizens and the world for as much as five or six weeks after it was first detected in the city of Wuhan in either the last week of November or early December.

Nor has the world’s medical guardian or its parent organization, the UN, mentioned Beijing’s outrageous mistreatment of the small band of doctors and medical researchers in China who bravely tried to alert people to the menace three weeks before the government there did.

During those three weeks, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s government was silent, allowing its people to go about their lives as if there was nothing wrong. As hundreds of millions of Chinese began the annual Lunar New Year trek to their birthplaces, the disease mouldered and grew before pinballing out on a thousand vectors around the world.

On the specific issue of Beijing’s extreme sensitivity to any geographic reference to the novel coronavirus in its official name, that position is bunkum.

Geographic locales where many of the world’s most dangerous pathogens were first detected have often been used as shorthand to describe them.

Among the many examples are three of the four most deadly viruses in the world: the Marburg virus, which was discovered in the German town of Marburg; the Ebola virus, named after a river in Congo near where the fatal fever was first found; and Lassa fever, which was discovered in the Nigerian town of that name.

In fact, on its official website, the WHO has long descriptions of both Ebola and Lassa fever using those names and providing the specific geography of those areas in West Africa.

Rather than blaming each other for a calamity that is already upon us, China and the U.S. should be collaborating on medical and economic solutions to this menace. That getting along with each other, at least for now, has not been an imperative for both countries is irresponsible. It has meant a much harder time of it for everyone.

Matthew Fisher is an international affairs columnist and foreign correspondent who has worked abroad for 35 years. You can follow him on Twitter at @mfisheroverseas.

Comments