More Albertan youths are suffering from poor mental health and advocates are calling for solutions.

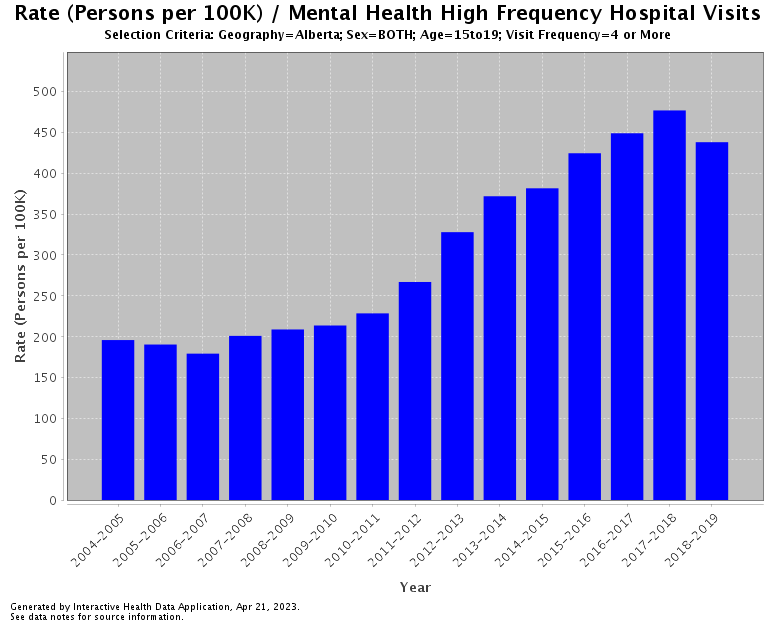

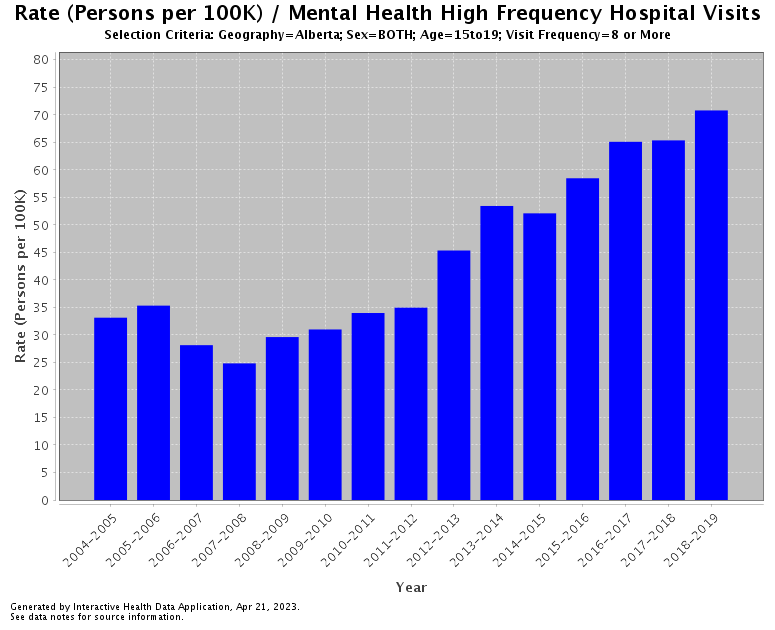

Data from the Alberta government’s Interactive Health Data Application shows more and more youth are visiting the hospital for mental-health-related in high frequencies year over year. The AHS defines high-frequency hospital visits as more than four visits or more than eight visits a year.

The rates are particularly high for those aged 15 to 19.

Data from 2019 to 2022 are not available on the Interactive Health Data Application as of April 26, but a report from the Alberta Medical Association said 77 per cent of parents reported the mental health of their child aged 15 and older is “worse” compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Four-in-ten parents of older teens said their child’s mental health is “much worse” as of June 2022.

Dr. Sam Wong, president of pediatrics for the Alberta Medical Association, said doctors are seeing more patients with anxiety, ADHD and depression.

An increase in screen time during the pandemic has contributed to the worsening mental health in teens and children, according to Wong, and eating disorders skyrocketed during the pandemic.

“You could make an argument that the content is not helpful. When you go onto Instagram, you see this person staying at a really nice hotel in Bali and all these beautiful places, and you look at your life and ask why yours is not the same,” he said.

“Social media is so pervasive now… You can’t escape bullying nowadays if you’re being bullied. You’re being bullied not just in person but on social media as well.

“When someone is making fun of you and bullying you on social media, that has a wider reach than when I was a kid… It’s a different generation and it’s a different environment that kids are growing up in now.”

Wong also said a shortage of mental health-care workers across the country has exacerbated issues throughout the pandemic. When there is a staff shortage nationwide, there isn’t a talent pool to recruit from.

“The pandemic was not helpful and tipped the balance even moreso. The number of health-care workers providing mental health supports was barely sufficient before the pandemic, and post-pandemic it’s certainly not enough to meet the demand,” he said.

“When you’re way short, where do you find people to do it if there’s not enough people coming in that aren’t being trained to do it? We are short on pediatric psychiatrists. We never had sufficient numbers of pediatric psychiatrists in Canada to meet that demand ever. Then you start seeing increased numbers of people needing these services.”

Different approaches needed for racialized youth

Missing from most conversations around youth mental health are the needs of racialized youth, particularly those who identify as Black or Indigenous.

Canada does not collect race-based health data, which means racialized youth are often falling through the cracks in the mental health-care system because of inequitable access to treatment.

Research from University of Alberta nursing professor Bukola Oladunni Salami found that Black youth disproportionately forego treatment and counselling when trying to address their mental health concerns.

Many of the Black youth she surveyed considered the lack of cultural safety and inclusion in the mental health-care sector a major concern. The system was designed to serve white people as the standard, Salami said, and the mere thought of potentially being “othered” is enough to deter Black youth from seeking care.

The popular “colour-blind” approach in therapy and counselling was seen as emotionally invalidating, damaging and draining, Salami noted in her research.

“Many of the youths go to a non-Black health-care professional, especially white professionals, and say they’re experiencing mental health and racism, and counsellors don’t understand how to deal with it,” Bukola told QR Calgary.

“They try to brush it off and move to something else because they’ve never experienced it and have not learned how to address the mental health of black youth who are experiencing racism from an anti-racist perspective.”

Indigenous youth face similar barriers.

Cynthia Wesley-Esquimaux, truth and reconciliation chair at Lakehead University, said a lot of Indigenous youth want to feel like they belong in a community.

“For a lot of people across the country, whether you’re Black or Indigenous or Asian, there needs to be a sense of belonging,” Wesley-Esquimaux said. “That’s what’s really missing for a lot of young people. They don’t have that sense of connection. They are sort of cast adrift with technology and they spend a lot of time talking to their friends online or watching things on their screens.”

Wesley-Esquimaux added a lot of youth carry on the trauma from their elders.

Mental health issues in Indigenous communities across Canada are often rooted in colonization. Research published in February 2020 said the historical and systemic colonialism to assimilate all Indigenous people has caused intergenerational harm within communities.

The loss of land, culture and language severely affected Indigenous people for generations. A lot of Indigenous youth do not respond well to traditional counselling methods.

“The Department of Indian Affairs provides access to resources for status Indigenous peoples and 12 sessions with a psychologist or psychiatrist, but it isn’t really accessible if you don’t know how to get to it,” Wesley-Esquimaux said.

“A lot of young people in rural and remote communities don’t want to talk to somebody like that either… There are so many nuances that go into the conversation around mental health and well-being that people don’t understand, especially if they come from outside and they don’t speak the language. But at the same time, they don’t want to tell anybody in their own community because they’re concerned that if I tell you what happened to me, you’re going to tell somebody else, and everybody’s going to know.”

Immigrant youth of colour (IYOC) face language and cultural barriers when trying to access support.

Farwa Naqvi is a researcher at the University of Calgary whose research focuses on the barriers IYOC face when trying to address their mental health concerns. She conducted 13 focus groups in urban and rural communities across Alberta, including places like Brooks and Red Deer.

She found that language barriers and income disparities are the top reasons why IYOC don’t seek mental health care treatment in rural areas. Most of the resources are in English and many of these children and teens aren’t fluent.

Many of these IYOC are also poor. In Brooks, many of the parents were recruited from African countries to work in meat plants in the area.

“A lot of these youth came up to me and asked how to apply for university and how to get into post-secondary. They worry about how they’re going to proceed in the future with their education and they don’t have any support for that,” Naqvi said.

“Their parents are working long hours and there is an income divide because their parents’ aren’t making that much. Not a lot of attention is being put on the kids. These kids try to make the best out of it.”

Stigmatization is also a huge issue within immigrant communities. Naqvi said there is a shared shame among immigrant youth regardless of race.

As a result, they feel much more isolated and lonely because they do not know where to get help.

“A lot of second- or third-generation youth who may be more ‘affluent’ have adapted and have a lot of resources in their community, but there is a shared shame that these youth have regarding their mental illnesses,” Naqvi said. “Parents will also feel the same in the community. The parents will try and go through religious or cultural avenues to kind of remedy their child’s mental health concerns, and that does not help the problem at all but exacerbates it.”

Community-based solutions needed

All four researchers emphasized the need for creative community-based solutions to address the youth mental health crisis.

Wong suggested group counselling sessions rather than private sessions for kids and teens who are struggling with mental illnesses.

“We have to start thinking outside the box… How do we deliver the resources in e cost-effective manner to as many people as possible?” he said.

“How do we develop a new paradigm and what is the most important and how do we do it in a cost-effective manner? That’s something the next government needs to address and something we need to do as the AMA.”

Wesley-Esquimaux said she is trying to get people in her nation to hang cards outside of her house to signal to kids and teens that their house is a safe space for them.

“Kids need somebody that they can go to, that they can trust,” she said. “Generally speaking, they’re not going to trust somebody that’s 10 or 20 years older, but somebody that’s 40 years older like a grandpa and grandma. If you have a fight with your mom or dad or a sibling, you can come to this house and spend an hour or however long you need while things cool off.”

For Salami, she would like to see more mentorship opportunities for Black youth. A lot of Black youth internalize negative stereotypes that are rooted in racism and xenophobia, she said.

“There’s a perception that you cannot achieve much because you’re Black, either from explicit comments or microaggressions,” the researcher said. “Many of the youths talked about the limited information related to Black history or Black role models in the school curriculum.

“A Black youth mentorship program will connect them to Black mentors for the first time… When you see another Black person doing well, it will positively influence the youth and spread positivity about Black history and Black identities.”

But both Wesley-Esquimaux and Salami noted resources for parents are critical as well. BIPOC children and teens are more likely to experience intergenerational trauma compared to their white counterparts.

Addressing the mental health of Black and Indigenous parents is important in solving the youth mental health crisis.

“Mental health is not just constrained within your individual perspective, but it’s also constrained within a family context,” Salami said.

Wesley-Esquimaux said kids will also seek help if they see their parents seek help.

“You can’t help a parent help their kids until they help themselves and they have to acknowledge themselves what happened so that they can actually put that foot down and not carry it forward,” she said.

“We act out everything… Kids hold up a perfect mirror to our behaviours.”

–With files from Kim Smith, Global News.

Comments