As Canadians reflect on the meaning of truth and reconciliation, one Nova Scotia Mi’kmaw woman says there’s opportunity through the history of hockey.

Cheryl Maloney, along with her sister, April, explored the connection of their Mi’kmaq ancestors to hockey, before it became Canada’s most popular sport.

They discovered there were Mi’kmaq words s for hockey-related terms before contact with Europeans. Their documentary The Game of Hockey – A Mi’kmaw Story includes pieces of history that were little-known or forgotten, including Mi’kmaq craftsmen making hockey sticks in the 1800s — sticks that were widely used in the early days of the National Hockey League.

“We had no clue when we started this that it would become such an amazing story,” says Cheryl Maloney. “And to, today, reflect on that, how that story was lost to not just my family, but to Canadians.”

She suggests reclaiming pride through history is one way to define the elusive concept of reconciliation.

“I think the game of hockey is such an amazing integral part of Canada and Canadians. And that if our children grow up knowing the Mi’kmaq had this amazing role in sharing this, can you imagine what that does for reconciliation?”

Some definitions of the term are pretty straightforward. According to the Oxford dictionary, it means “the restoration of friendly relations.” But an effort to develop a “reconciliation barometer” — to define and measure progress — is still incomplete as researchers consider a wide range of indicators.

Get breaking National news

Katherine Starzyk is leading the project at the University of Manitoba’s Social Justice Laboratory in Winnipeg. She says a total of 13 indicators are being considered for inclusion in the barometer.

“Understanding what’s happened, the connection between the past and the present, current inequalities and strengths within communities,” Starzyk said.

Team members include Aleah Fontaine, who has Anishinaabe family members who survived residential schools.

“By looking at these different indicators, we can get a better sense of what are we doing well, where are we not doing well, and where do we then need to focus our efforts,” Fontaine said.

They plan to complete their “reconciliation barometer” later this year, after six years of planning.

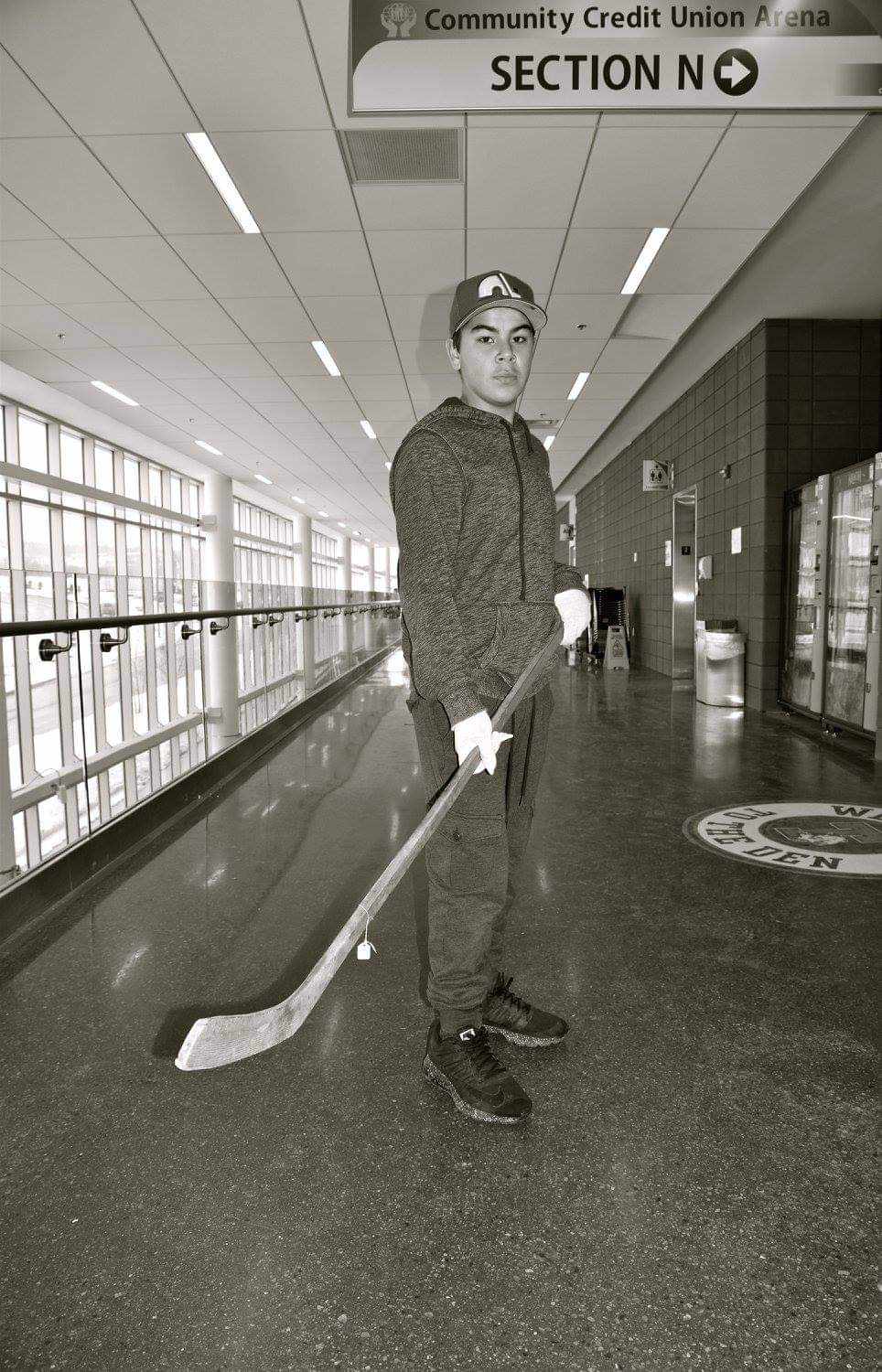

Back in Nova Scotia, Cheryl Maloney has found another point of pride: her son Chase posed with a stick from 1917, after they discovered it was handmade by his great, great grandfather, Alexander Cope.

However, Maloney says her research is not about debunking other claims about where the game of hockey began.

“We’re just trying to acknowledge, you know, the roots of this game and the role of the Mi’kmaq people. And I think that’s something great for Canadians that we can celebrate.”

Comments