On Jan. 30, 1961, acting on information uncovered by the RCMP, Britain’s MI-5 security service examined the penis of a man who purported to be a Canadian named Gordon Lonsdale and confirmed he was a KGB spy.

It was the turning point of a key Cold War counter-espionage operation that outed Konon Trofimovich Molody as a Russian “illegal” — a deep-cover Soviet agent who had taken over Lonsdale’s identity.

Stealing the identities of Canadians is a common Russian spy stunt, but choosing Molody to double as Lonsdale was a fatal oversight by the KGB, and one the RCMP helped expose.

The RCMP played a “crucial role,” says Trevor Barnes, the author of a new book on what became known as the Portland Spy Ring, in an interview with Global News.

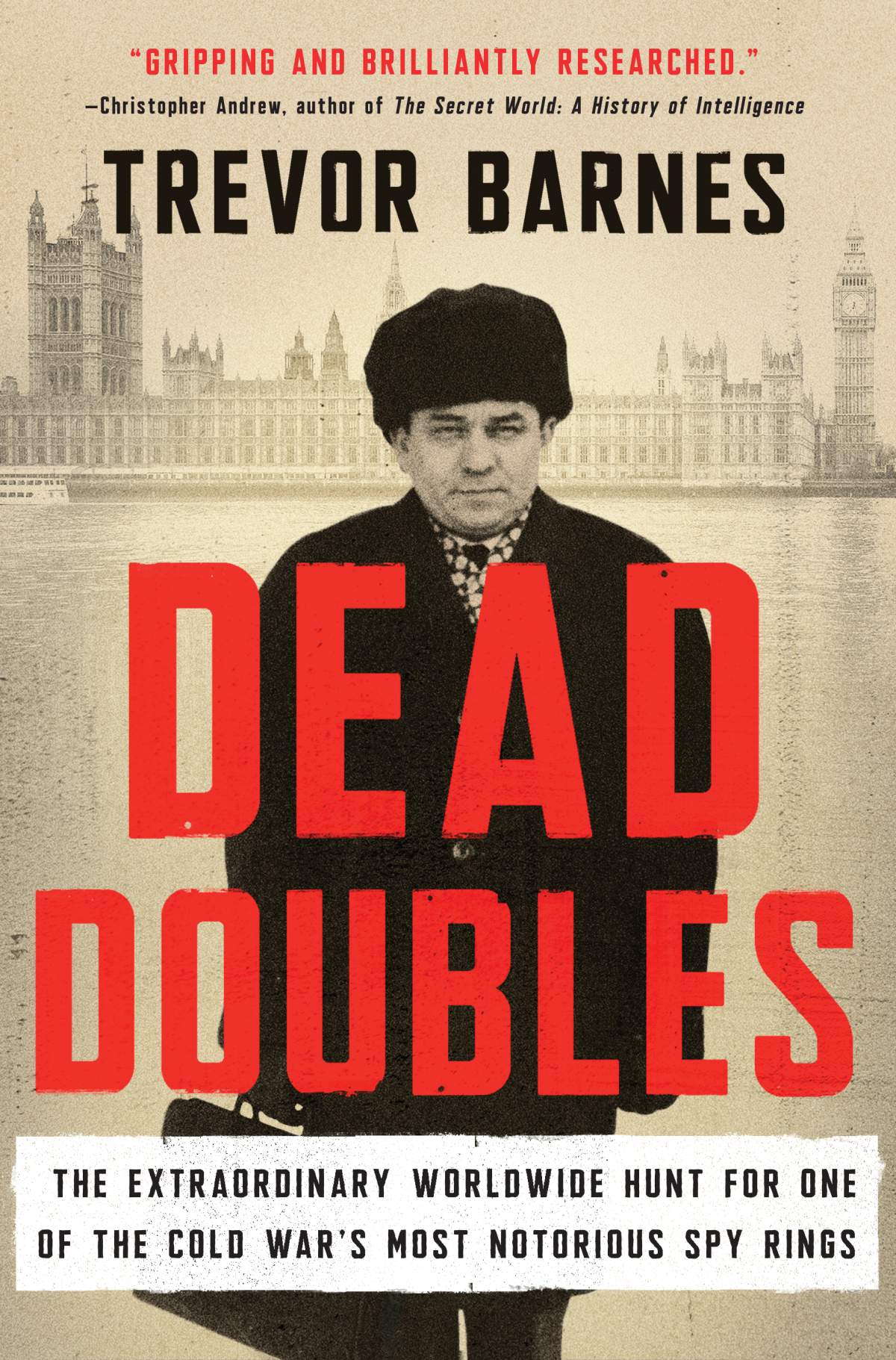

In Dead Doubles, Barnes mines newly declassified MI-5 case files to unravel the story of what the British call one of their “most significant post-war counter-espionage cases.”

The investigation began after the CIA learned from an informant, code-named Sniper, that secrets from a highly-sensitive Royal Navy research facility in Portland, England, were making their way to the Soviets.

MI-5 soon focused on Harry Houghton, a former British naval attaché in Warsaw who fit the profile supplied by Sniper. While under surveillance, Houghton met in London with a man MI-5 identified as a Canadian jukebox salesman, Gordon Lonsdale.

To discern whether Lonsdale might be also a spy, MI-5 had a discreet look in his safe deposit box and discovered “a treasure trove of KGB spy paraphernalia,” Barnes said.

Notably, hidden in a cigarette lighter, MI-5 operatives found cipher pads of the type used by the Soviets to decode incoming radio messages and encode outgoing ones.

The RCMP subsequently began to investigate Lonsdale, but could find little about him, except that he was born in Cobalt, Ont., in 1924 and had obtained a driver’s licence in Vancouver in 1954. In 1955, he had applied for a passport.

Beyond that, the RCMP security service struggled to find any trace of the man. There were scant records or witnesses who recalled him. His life in Canada was “shrouded in darkness,” wrote the MI-5 officer in charge of the investigation.

Get daily National news

“This total absence of documentation is perhaps the most revealing piece of evidence that Lonsdale is an illegal intelligence agent.”

As it turned out, it wasn’t actually the most revealing piece of evidence.

The CIA informant Sniper defected in January 1961, forcing MI-5 to round up its spy ring suspects, including Lonsdale and two others posing as Canadians. But MI-5 needed “irrefutable evidence” that the man who said he was Lonsdale was an imposter, Barnes said.

So the RCMP kept at it, and on Jan. 16, 1961, they reported to MI-5 they had found something: Lonsdale’s father in northern Ontario had given a statement, and he was adamant his son had been circumcised.

“And so they had a pretty immediate and very confidential medical exam of certain private parts of Lonsdale,” Barnes said. He was not circumcised. “So that was a crucial bit of information for MI-5 because they knew that this man was not who he pretended to be.”

Further digging determined that the real Lonsdale had left Canada with his mother as a child. She had separated from her husband and moved to the Soviet Union. Lonsdale had died in his youth, and the opportunistic KGB had helped itself to his Canadian documentation.

Using Lonsdale’s identity, Molody had arrived in Canada in 1953 to establish his “legend.” He lived in Vancouver and Toronto before making his way to the United States and Britain, where he became Houghton’s KGB contact. He was “a very capable spy,” Barnes writes in Dead Doubles, which is to be released in September.

Lonsdale later claimed Houghton had leaked hundreds of documents on anti-submarine equipment and nuclear submarines to Moscow, which MI-5 believed had “helped in the manufacture of a new and more silent generation of Soviet submarines.”

When he was returned to the Soviet Union in a spy swap in exchange for an MI-6 agent, Greville Wynne, Molody was awarded the Honorary Security Officer medal for his “great services to the Motherland.” The Soviets even put him on a stamp.

The other two members of the spy ring posing as Canadians, Lona and Morris Cohen, had long been sought by the FBI. Lona Cohen had been a KGB courier, sent to Canada to collect documents and, on one occasion, a uranium sample, from the atomic research centre at Chalk River.

Even after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia continued sending “illegals” to Canada to assume false identities, often chosen by “tombstoning” — trolling graveyards looking for deceased children whose lives they could exploit.

In 1996, CSIS caught a pair of Russian spies who were living in Toronto as a married couple, Ian and Laurie Lambert. They were using the identities of two Canadians who died as infants.

Another Russian illegal was arrested in 2006 in Montreal, where he was living as Paul William Hampel. Again in 2010, two Russian spies using the names of dead Canadian children, Ann Foley and Don Heathfield, were caught by the FBI.

Barnes recounted meeting in Moscow with “Foley,” whose real name is Elena Vavilova. Her two Canadian-born sons fought Ottawa’s efforts to strip their citizenship. The Supreme Court sided with the spy’s sons in December 2019.

READ MORE: Relieved Canadian son of Russian spies flies to Toronto after citizenship affirmed

“There is this dispute about whether the kids actually knew or not, and she of course, understandably, told me that they didn’t have any idea,” the author said.

Russia has undoubtedly continued to use illegals to supplement its contingent of intelligence officers operating under diplomatic cover at the Canadian embassy in Ottawa.

“It can be very effective,” Barnes said of the use of illegals. “Because clearly if you are successfully established as an illegal, you are hopefully not going to be on the radar screen of the intelligence agencies of the country that you’re trying to penetrate.”

“That’s the real advantage.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.