The sense of alienation in Western Canada is nothing new, but it is changing.

It has narrowed geographically to Alberta and Saskatchewan, but in those two provinces it has also intensified. On an issue as critical to the country as national unity — it is good that the sentiment is not more widespread. But it is not good that this essential piece of the Canadian fabric feels less connected to the rest of the country after Monday’s election.

It’s fair to say that rural parts of British Columbia and Manitoba were of similar mind in their voting patterns, but those two provinces are an expression of multi-hued political diversity compared with the almost uniformly blue maps painted in Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Conservatives won two Saskatchewan ridings with more than 80 per cent of the vote. Similar routs were even more frequent in Alberta, where Conservatives won some races by more than 40,000 votes.

In the riding of Battle River-Crowfoot, Conservative Damien Kurek received more than 85 per cent support, the New Democrat got 5 per cent, the Liberal 4 per cent. It’s stunning compared with the rest of the country, where our multi-party elections send the vast majority of MPs to Ottawa with far less than 50 per cent support from their own constituents.

It helps explain the strong reaction to the Liberals’ victory that we saw from Alberta Premier Jason Kenney and Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe. It’s easier to reflect your constituents’ wishes when their wishes are so one-sided.

So how is it that Western Canada’s grievances have changed, both narrowing geographically and becoming more intense where it does exist?

Darrell Bricker of Ipsos has been studying political trends in Canada for years. Whether it was in oil and gas or in agriculture, he says the feeling among many western Canadians is that larger political interests have redirected the benefits of western wealth towards the east.

“There’s always been a sense regardless of what the industry is in places like Saskatchewan and Alberta that Central Canada somehow works against them,” says Bricker.

Forty years ago, by the time Pierre Trudeau had been in power for a decade, the disenchantment with Liberal governments in the West spanned from Manitoba to Vancouver Island. This was the period when oil prices spiked and the National Energy Program sought to give Ottawa greater control over the oil industry. In the 1979 election, the Liberals won a total of three seats across the four western provinces. In 1980, they won two, and that was in a majority Trudeau government. And in ’84, many will remember, the Liberals hung onto one seat in Winnipeg with Lloyd Axworthy, and one seat in Vancouver, that of their beleaguered leader, John Turner.

READ MORE: With the Liberals’ new minority, Trudeau’s greatest challenge is healing divide with Western Canada

Get breaking National news

What followed were successive Progressive Conservative majority governments under Brian Mulroney. But even that did not satisfy the western desire to have a louder voice in Ottawa. And so for a time, westerners got behind an unabashed western movement, the Reform Party. It was then that Ipsos began sampling westerners’ views about their place in Canada and in Confederation.

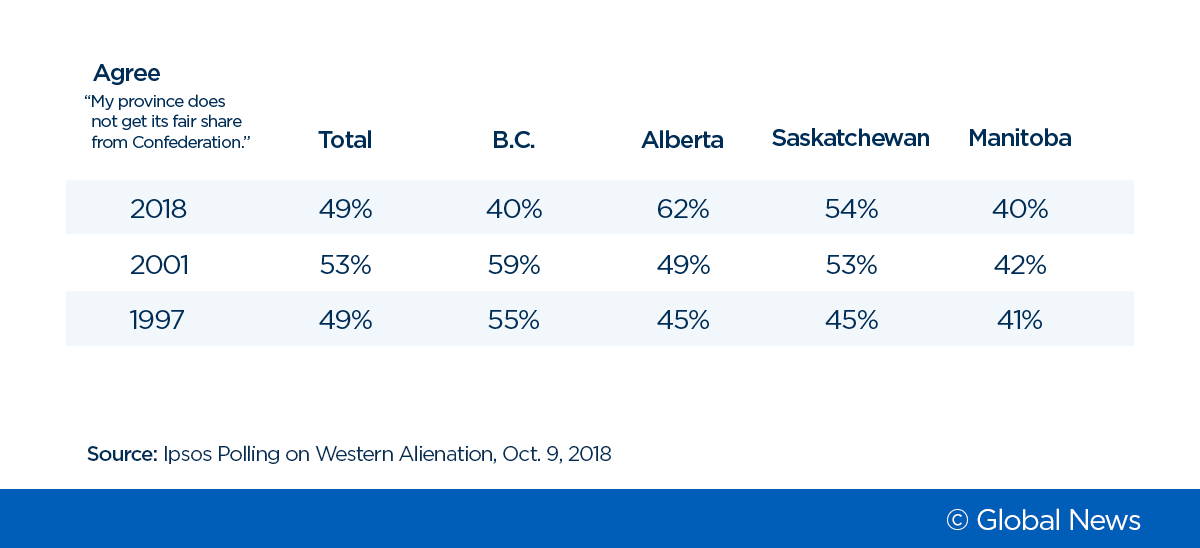

At the time, half (49 per cent) of those surveyed in Western Canada agreed that with the statement, ‘My province does not get its fair share from Confederation’. British Columbia actually led the way at 55 per cent. Alberta and Saskatchewan at 45 per cent each, and Manitoba at 41 per cent. The data shows that Manitoba has always been less strident when it comes to its western identity.

Ipsos asked the question in 1997, then again in 2001 and 2018, just one year ago. Over those 21 years, the numbers moved among the three western-most provinces. Those who felt Saskatchewan doesn’t get a fair shake increased from 45 per cent to 54 per cent. In Alberta, the numbers spiked from 45 per cent to 62 per cent. In the wake of Monday’s election, one could reasonably conclude that Albertans feel even more so this week that they are not getting a fair shake from Confederation.

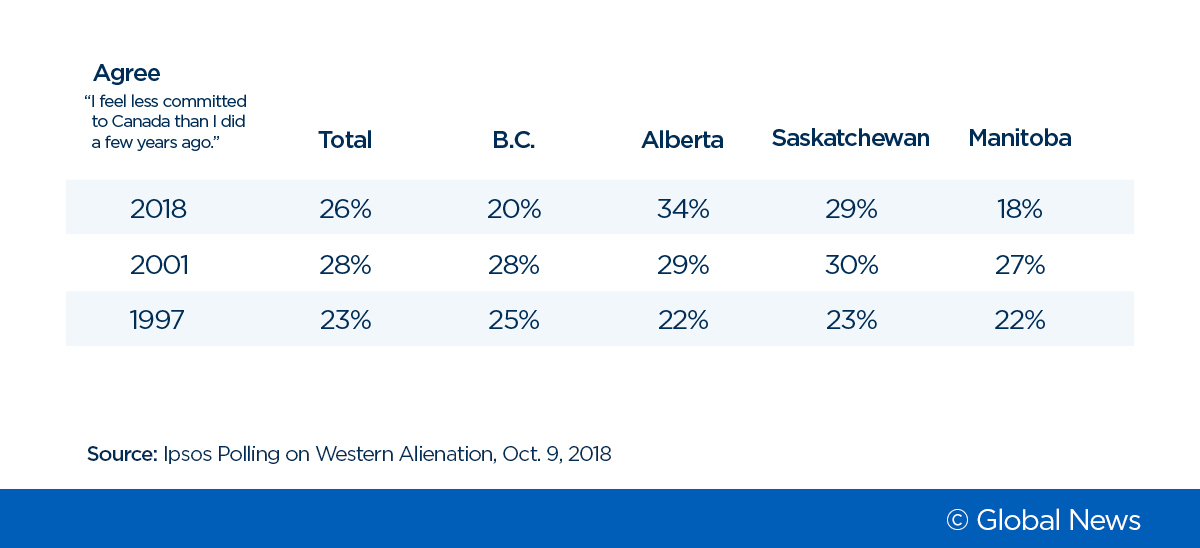

On the statement, ‘I feel less committed to Canada than I did a few years ago’, again the sentiment of less commitment increased over one generation in Saskatchewan from 23 per cent to 29 per cent, while Albertans’ loss of commitment jumped from 22 per cent to 34 per cent.

On both questions, however, British Columbians have moved in the opposite direction. Concern that they are not getting their fair share from Confederation has dropped 15 points from 55 per cent to 40 per cent. And fewer British Columbians feel less committed to Canada than a few years ago.

Bricker says people in British Columbia might not like the comparison, but B.C., he says, “is increasingly looking like Ontario, where you have a downtown very much more oriented toward the Liberal party, progressive options, the Green Party, the NDP, where suburban and rural British Columbia, smaller towns, looks more blue and is more conservative.”

Ipsos found Manitoba is more like B.C. about its place in Confederation, its commitment to Canada. And in the way it votes — even with the western shift away from the Liberals on election night, the Winnipeg electoral map remains a colourful mix of four red Liberal ridings, two orange NDP districts and two Conservative ridings, surrounded of course by Conservative blue as far as the eye can see in Manitoba farm country.

In short, B.C. and Manitoba are moving away from that sense of western alienation. Today, it is probably more accurate to call it Prairie alienation (and other pockets, perhaps, like northeastern B.C.).

READ MORE: Tory blue wave sweeps Alberta, Saskatchewan, bringing challenges with Liberal minority

And the fact is, Saskatchewan and Alberta are feeling it more than ever. Their anxiety is genuine, and almost certainly revolves around the fossil fuel economy. Oil and gas, and up to now even coal, are all massive parts of the economic foundation of Saskatchewan and Alberta in ways that none of those resources are relied upon in the rest of Canada.

Except, of course, they are relied upon by the rest of Canada. We’re all addicted to oil and gas in our cars, our homes and in our industries.

But the debate isn’t the same squabble we once had over the shared economic benefits of the carbon economy. Now, it is seen as a fight for survival. Alberta and to a lesser extent Saskatchewan are worried that climate change isn’t just another cyclical dip in the industry’s boom-bust rollercoaster, but threatens to permanently bust the oil economy. Large investors needed in the oil sector are beginning to shy away from the oil sands. The fear is real that what has sustained the prairie economy for decades may be slipping away.

A cry went out on Monday night with the vote we saw in Alberta and Saskatchewan. In the aftermath, Scott Moe declared, “We are at a crossroads in this nation. And we are asking (Trudeau) to change course… to respect a new deal with Saskatchewan and the provinces, a deal that would do away with the carbon tax.” But the cry to kill the carbon tax has been met with a louder response from the so-called progressives across Canada: “Do more, not less on climate change, our future depends on it.” If the Conservatives had narrowly won the election and tried to roll back carbon taxes, imagine the outrage we would be witnessing today from the 60+ per cent of Canadians who voted for parties that accept carbon pricing.

So, both sides now see an existential threat. The stakes are that high.

READ MORE: Separatist talk renews in Alberta following Justin Trudeau Liberal victory

Scott Moe must know this. Just as he must know Saskatchewan has four per cent of the population, and with Alberta’s 10 per cent, simply must find other partners to ultimately affect Canada’s climate policy. The political map may show a big blue swath across the prairies, but a map with 338 ridings equally distributed paints a more realistic picture. Even a growing Alberta and Saskatchewan cannot outvote Ontario. (In fact, Ontario elected more Conservatives than Alberta). As Darrell Bricker observed, “You can’t win a national government with the West alone.”

And it is probably true that no future Conservative party can or will come forward with a climate plan that appeals to only 34 per cent of the nation. Because on that issue, the other 65 per cent have a common cause to stop them. Remember, the NDP, the Greens and the BQ got 30 per cent of the national vote, and would go further than the Liberals on climate, ending new pipeline construction.

The irony is that Alberta and Saskatchewan, which gave Justin Trudeau zero MPs, now need Trudeau and his 33 per cent mandate, to help their carbon-based economy evolve, in a world inescapably in the throes of climate change.

.jpg?h=article-hero-560-keepratio&w=article-hero-small-keepratio&crop=1&quality=70&strip=all)

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.