Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau has promised to increase the number of family physicians and allocate funding to ensure that “all Canadians have access to a family doctor.”

“Having access to the right doctors and the right treatments can make all the difference,” Trudeau said on Monday during his announcement that a re-elected Liberal government would allocate $6 billion to improve the health care system. The Liberals have yet to release their full platform.

When Trudeau was asked by Global National’s Dawna Friesen on Tuesday whether he was promising more family doctors, he said: “Yes. We are making a commitment that the federal money invested in health care is going to help more Canadians get… help Canadians get family doctors.”

WATCH BELOW: Trudeau asked how he intends to fund $6B medicare investment

However, a new report shows that the number of doctors has been increasing across the country over recent years, even outpacing the rate of growth of the Canadian population. And health experts say that improving access to primary care will require complex and specific strategies not articulated so far by the Liberal proposal, or that of other parties.

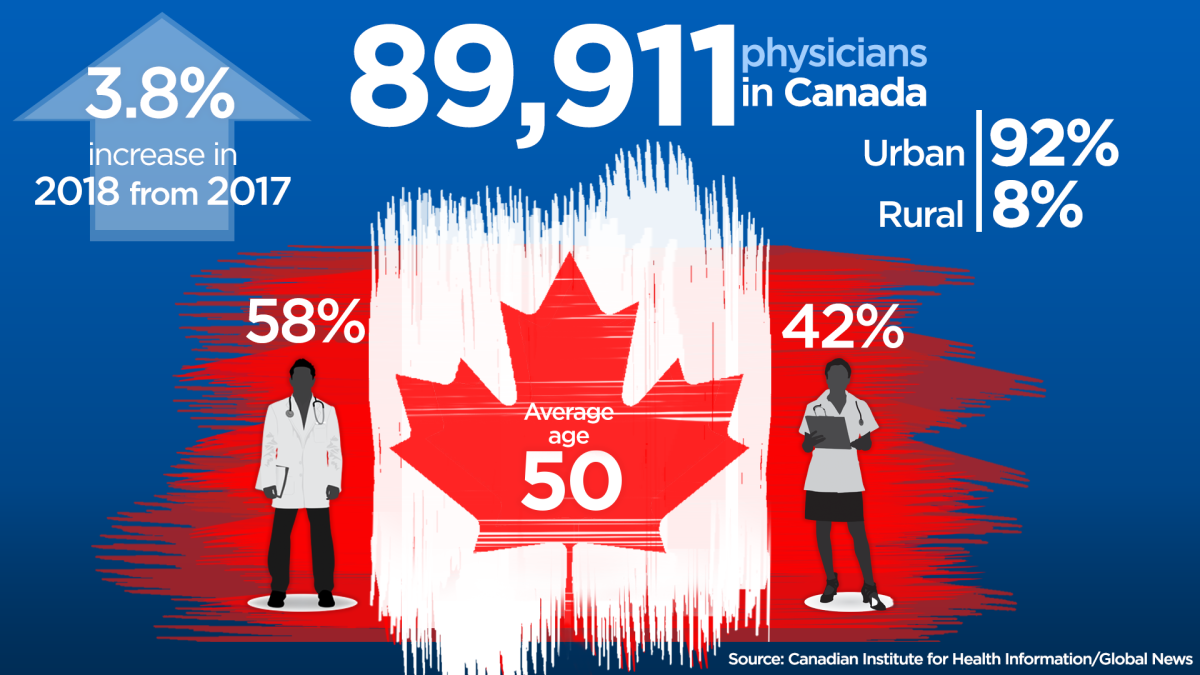

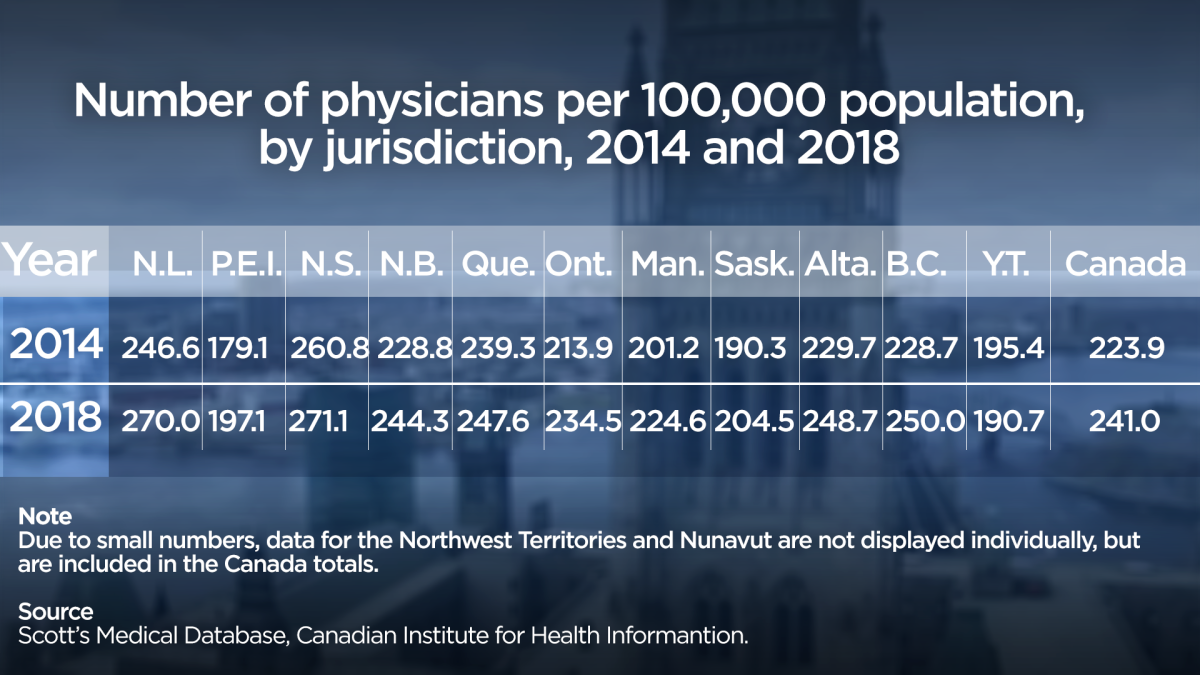

From 2014 to 2018, the population of doctors grew by 12.5 per cent, three times higher than the 4.6 per cent growth of the general Canadian population over the same time period, according to a report released Thursday by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). Half of the number of doctors counted are family doctors.

Still, Statistics Canada has estimated that 4.7 million people in Canada do not have a primary health provider.

The CIHI report shows that in 2018, there were nearly 90,000 doctors in Canada, amounting to 241 physicians per 100,000 population — the highest number per capita ever. It also shows that the vast majority of physicians, 92 per cent, work in urban centres, meaning that only 8 per cent work in rural areas.

READ MORE: Kingston couple sift through red tape in search of family doctor

Get daily National news

“We are seeing this steady growth in the number of doctors in the country. And we’re also seeing that the number of Canadians who are having challenges accessing a doctor hasn’t budged that much,” Geoff Ballinger, manager of physician information at CIHI told Global News. He added that the growth in the number of physicians is expected to continue over the next couple of years at least.

He said that provincial governments, which have jurisdiction over healthcare delivery, can provide a number of incentives to encourage doctors to work in rural areas.

“More work needs to be done to be sure they’re where people need them most,” Ballinger said.

The Green Party platform states that it will “work to ensure that every Canadian has a family doctor and that primary care is centred on the patient and is sensitive to issues of social justice, equity and cultural appropriateness,” but does not provide details.

The NDP is pledging to work with the provinces and territories to “tackle wait times and improve access to primary care across the country. We will identify coming gaps in health human resources and make a plan to recruit and retain the doctors, nurses, and other health professionals Canadians need.”

While the Conservatives, like the Liberals, haven’t released their full platform, leader Andrew Scheer recently promised his government would spend $1.5 billion on new medical equipment, and has said his party would maintain and increase the Canada Health Transfer.

Dr. Rita McCracken, a family doctor and researcher at the University of British Columbia, said that government promises to increase the number of doctors and funding will not necessarily solve the problem of access to primary care, and that any government proposal needs to be backed up with specific measures and goals.

McCracken referenced a campaign promise by the B.C. Liberals in 2010 and 2013 dubbed “A GP for Me” that would ensure everyone in the province who wanted one would have access to a general practitioner.

But by 2015, hundreds of thousands of people there were still without a family physician.

WATCH BELOW: NDP announces plan for government-funded dental care

“The reason why the GP for Me program in British Columbia didn’t work was that we just offered more money,” McCracken told Global News.

She said that while the goal of increasing access to a family doctor is great, it’s important that there are clear metrics being followed to make sure financial investments are actually producing the desired results.

“In British Columbia, we saw doctors getting more money and not much change. In fact, actually a decrease in the number of people who were attached to family doctors,” she said.

For McCracken, the models of primary care need to be updated to more efficiently serve the needs of the community. So moving beyond the more traditional family doctors’ offices, where a doctor runs the office like a business, with a significant amount of overhead and staffing pressures.

WATCH BELOW: Liberals pledge national pharmacare

“We need that structural shift,” she said, pointing to the need for more community-based clinics where doctors are salaried employees and have more flexibility.

Though healthcare is largely a provincial matter, McCracken said the federal government “has an opportunity around structure.” So if the federal government were to endorse and invest in clinical service delivery models, such as community health centres, then the provinces would have to figure out how to deliver on that.

“Really endorsing that idea of creating healthcare centres within a community, rather than just giving the money to doctors, as was originally designed in the medicare program,” McCracken said.

Ballinger said it’s positive the numbers show an increasing number of physicians.

“It’s encouraging, particularly for those Canadians who are having challenges to find a doctor, that there are more who are practising and we are also aware that there are more in the pipeline,” Ballinger said.

“The crux of the issue is trying to see improved access and also to see improved outcomes as a result of that access.”

Comments