The impact of residential schools has never been so apparent, after two doctors said provincial data indicates that generational trauma has re-emerged among First Nation youth in the form of a suicide crisis.

On Friday, the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations (FSIN) released its discussion paper in full on the matter.

READ MORE: FSIN developing Indigenous suicide prevention strategy

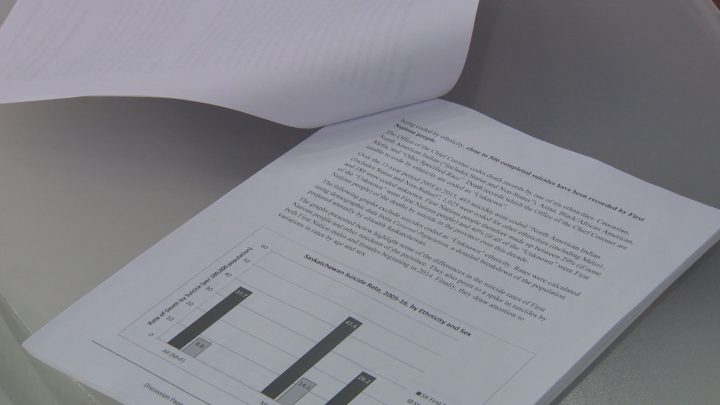

The 24-page document was sent to all chiefs and health directors outlining the number of deaths by suicide among First Nations people in Saskatchewan.

According to researchers, there hasn’t been anything like this paper where suicide data was compiled by First Nations people for First Nations people.

READ MORE: Saskatoon man in uphill fight over residential school compensation

Since 2005, when deaths began to be coded by ethnicity – close to 500 completed suicides have been recorded by First Nations people. Approximately 62 per cent of all suicides were by a person under the age of 30.

Other startling statistics in the report included:

- the rate for First Nations girls, aged 10 to 19, is 26 times higher than that of non-First Nations girls;

- First Nations boys are six times more likely to commit suicide; and

- 25 per cent of all suicides by First Nations people were teenagers.

Get daily National news

“Something that really stands out for me is they’re addressing a suicide crisis,” FSIN vice-chief Heather Bear said.

“We know that our northern communities and southern communities are faced with young people with no hope.”

By mid-November, all First Nations in the province are encouraged to provide feedback on the paper’s findings.

It’s a launch pad towards a “First Nations Suicide Prevention Strategy” believed to be the only one of its kind in the country.

At present, Canada is only one of two developed countries without a strategy so officials said it’s no wonder our province doesn’t have one.

As for why rates are so much higher among First Nation youth, Dr. Jack Hicks said one theory is early childhood adversity.

“We can look at all the things that are happening in the communities, all the different kinds of social change, stress in families, inadequate services, unemployment and poverty,” Hicks said.

“They’re impacting young people today in a different way than was the case say 40 years ago.”

READ MORE: Sask. man who organized vigil says Chester Bennington helped him with depression

What needs to happen now, said Hicks, an adjunct professor at the University of Saskatchewan in the community health and epidemiology department, is to focus on how the youth’s childhoods differed from their parents.

“I think on average, young people today have much more challenging childhoods and youth experience than was the case for their parents or grandparents.”

According to his colleague, clinical psychologist Dr. Kim McKay-McNabb, children and youth now more than ever before are feeling the effects of residential schools and they often have nowhere to turn for help.

“First Nations people don’t have the same access as other people in the province to mental health supports,” McKay-McNabb said.

“We do not have specific family healing centres that are geared towards assisting us as First Nations people to heal from those traumas.”

Based on what they’ve seen so far, both doctors say it’s imperative that something is done now.

“What happens today might increase or lower the suicide rate 10, 15, 20 years from now,” Hicks said.

The official suicide prevention strategy will be released on May 31, 2018, but officials will meet in October to discuss ways they can arm communities with short-term strategies.

In the meantime, Bear made a plea to youth across the province.

“Do not lose hope, because you matter.”

Comments