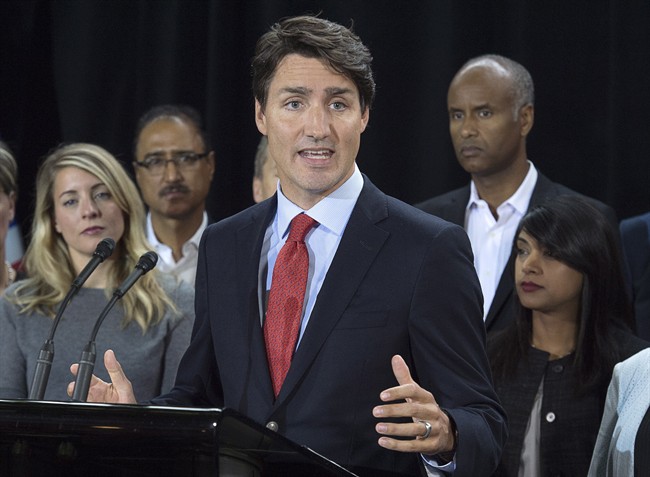

Will Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s proposed tax changes soak the rich and help the middle class as the Liberal government has been saying? Or will they also harm small businesses with middling incomes, as critics contend?

READ MORE: Trudeau’s tax reforms: Here’s how the loopholes work

There are a number of conflicting statements and headlines out there about what the impact that Ottawa’s tax reforms on Canadian private corporations would truly be.

To help Canadians make sense of it all, Global News has spoken to experts on both sides of the debate to check claims about who will really be affected and how. Here’s what we found.

READ MORE: Will Trudeau’s reforms really mean 73% tax for small business?

Will the tax changes really hit…

… wealthy tax cheats?

The short answer here is this isn’t about tax cheats. The word “tax cheat” has come up a lot in this debate because the government has referred to the reforms as intended to close tax loopholes. Understandably, in many people’s minds, “tax loopholes” goes hand-in-hand with “tax cheats.”

But if by tax cheat we mean people who break the law by hiding money from the government, this is not about them. That’s tax evasion, and, yes, it is a problem but a different one, and one that Ottawa has long been fighting with a different set of measures.

READ MORE: CRA expects to track down $400M in tax crackdown

The tax reforms the Trudeau government is proposing would change a set of tax rules that the government believes are no longer achieving their intended objective. These provisions were meant to help small businesses and other private corporations grow and create jobs but are increasingly being used by high earners to shrink their tax burden.

The government should have never used the word “loophole” when talking about these reforms, said Lindsay Tedds, an economics professor and tax policy expert at the University of Victoria.

Many critics of the government’s proposals actually agree that Canada’s corporate tax regime needs a rethink. They disagree on what the fixes should be.

WATCH: Majority of Canadians against support tax reforms to small businesses: Ipsos

… the rich?

Prime Minister Trudeau has said the tax changes are aimed at those making $150,000 a year or more. Many others contend the changes will affect small business owners who take home far less than that.

According to Jack Mintz, an economist at the University of Calgary and one of Canada’s foremost tax experts, 70 per cent of small business families who would be affected by the proposed changes have a household income below $200,000. “These are not Canada’s one-percenters,” he recently wrote in the National Post.

READ MORE: Saskatchewan farmers and small businesses protest proposed tax changes

Indeed, it would be incorrect to say that people making less than $200,000 (or $150,000, to use the government’s figure) won’t see any impacts from the reforms, said Tedds.

But the current tax provisions only yield significant advantages to people making more than that, she noted. So closing them would mostly hurt the rich.

For example, what is arguably the most controversial of the Liberals’ three major tax proposals would increase taxes on so-called passive investments, i.e. surplus profits held inside corporations that aren’t immediately reinvested in the business on things like new hires or equipment.

READ MORE: Tax changes do not impact family trusts or numbered companies, used by Trudeau, Morneau

Because such investments are relatively lightly taxed in the current system, it can be very advantageous for business owners to accumulate money inside their corporation in order to build up their personal savings.

As Global News has noted before, someone making $250,000 annually and using $100,000 a year for living expenses could end up with an after-tax retirement nest egg of up to $3.4 million after 25 years (assuming a 6 per cent rate of return on investment).

Under the same assumptions, someone with the same income and living expenses who doesn’t have a corporation and only has access to an RRSP and a TFSA would end up with $2.8 million at the end of the period, an 18 per cent difference.

READ MORE: Canadian business owners aren’t quite united over Trudeau’s tax reforms: Angus Reid poll

According to the Department of Finance, many people have noticed this tax advantage and larger and larger amounts of money are being stashed inside corporations as a result. If those passive investments aren’t used for corporate purposes (for example, to build up a company’s rainy day fund or fund longer-term investments, which could still help create jobs and grow the economy in the long run), then the current rules result in lost revenue for the government and an unfair system in which some Canadians get to pay less tax on their personal savings.

Further, government numbers indicate that only 300,000 private corporations report any passive investment, with half of those not making enough income to be impacted by the reforms, according to the National Post.

Get weekly money news

In order to level the playing field, the Liberals want to raise the taxes that business owners would pay when they withdraw their passive investments.

Critics have noted that this would hit even middle-income business owners trying to save for retirement or other personal needs. It would also impose higher taxes on businesses who do use passive income for corporate purposes.

WATCH: Trudeau speaks on tax changes, immigration during packed Kelowna town hall

However, there are two things to note here.

One, when it comes to preparing for retirement, small business owners who aren’t high earners are better off saving like most other Canadians, according to Tedds. The big advantage of using lightly taxed passive income inside a corporation comes into play for those who have considerably more savings than they can fit into tax-efficient savings vehicles like RRSPs and TFSAs.

The RRSP contribution room is 18 per cent of your yearly earned income, up to a cap of around $26,000. This means you’d need around $144,000 in earned income in order to hit that ceiling. In addition to that, you could put another $5,500 a year into a TFSA. In other words, this tax strategy doesn’t really make sense for anyone earning less than $150,000 a year, which is where the government is likely coming from.

Even if you move slightly above that, the advantage for business owners of stashing their personal savings inside a corporation isn’t straightforward. A CIBC report published months before the reforms were announced shows that a business owner making $170,000 a year would almost always be able to save more after 30 years by paying herself a salary and using an RRSP than by investing passive income inside a corporation.

(Business owners can choose to pay themselves via dividends or salary. The taxes are roughly equivalent but having a salary allows them to pay into the Canada Pension Plan and accumulate RRSP room, whereas dividends do not.)

READ MORE: Tax reform: Scheer says Trudeau’s ‘arrogance is astounding’

There’s another issue, though. Small business owners often must reinvest in their company for many years before having enough income to be able to contribute to an RRSP.

“These owners will never be able to accumulate a reasonable amount of retirement savings using only RRSPs and TFSAs,” Allan Lanthier, a former senior partner at EY and former chair of the Canadian Tax Foundation, recently wrote in the National Post.

And yet, that’s true of anyone who must invest in upfront costs and forgo income, noted Tedds: “Why do only incorporated businesses get a capital advantage?”

This is an issue that could be tackled through broader measures specifically designed to help all Canadians in this situation save, she added.

So what about businesses that want to retain surplus profits as passive income to pay for future company expenses and investments?

According to Kevin Milligan, a professor of economics at the University of British Columbia who has advised the Liberals in the past, the amount of additional tax that businesses would face “is not large for modest amounts of saving.”

For example, someone with $100,000 to invest as passive income under the new rules would end up paying only $430 more in taxes after withdrawing the money from the corporation after a year, assuming a 3 per cent investment return.

“The bigger impact happens with compound interest over the long run for people with large passive portfolios,” Milligan told Global News via email.

WATCH: Conservative leader Andrew Scheer blasts Trudeau for targeting small businesses

… middle-class small business owners?

The Liberals are proposing two other sets of measures that critics say will hit middle-class entrepreneurs along with high earners.

The first is aimed at current tax provisions that allow small-business owners to split their income with family members by paying them dividends even if they’re not directly involved in the company. So-called income sprinkling is particularly advantageous for families where the small-business owner would place in the highest tax bracket but his or her spouse and adult children have very little or no income, which puts them in a low bracket.

“When the tax rate gap is big – which is true for high earners – the tax savings are substantial,” noted Milligan. By contrast, for middle-income families, “the savings from sprinkling would be very small because the gap in the tax rates between the spouses is small.”

Still, in order to deter the practice, the government is proposing a “reasonableness test” aimed at assessing whether family members receiving dividends are actually involved in the business.

READ MORE: Ex-Liberal finance minister says Trudeau’s tax changes driving out businesses

Tax accountants and economists worry that this will introduce both red-tape and tax-time uncertainty for small businesses that share income among relatives who truly are involved in the company. After all, what exactly will the Canada Revenue Agency consider reasonable?

Another major concern for small business owners is the government’s planned crackdown on the practice of, essentially, turning corporate income into lower-taxed capital gains by transferring shares through a series of connected corporations.

The Canadian Federation of Independent Business and several accountants say the proposed rule changes would also punish business owners selling their business to their children.

According to the analysis, the cost would surpass what a buyer not related to the family would pay to purchase the business.

WATCH: Liberals accuse Conservatives of ‘scare tactics’ against tax reforms

… doctors and lawyers?

The reforms also affect many self-employed Canadians, like doctors and lawyers, who often operate as private corporations.

A number of professionals have received permission to incorporate in recent years, which has helped boost the number of private Canadian corporations.

Indeed, their ranks have ballooned from 1.2 million in 2001 to 1.8 million in 2014, according to the Department of Finance. Among self-employed professionals, the number has tripled over 15 years.

Doctors, in particular, the vast majority of whom operate as small businesses, have been vocal in their opposition to the tax changes. The Canadian Medical Association has argued that the new rules would make it harder for doctors to save for retirement and parental leave, among other things, and may lead some to shrink their practice or reduce their hours.

On the other hand, several economists have noted that incorporated professionals, including doctors, currently enjoy a preferential tax treatment that other self-employed Canadians without stable salaries, benefits or pensions do not have access to.

READ MORE: It might not be much, but business owners and doctors can get federal mat leave benefits

Canada may well need policies that do more to help the self-employed, but allowing a specific group of people to keep using certain tax rules in ways they weren’t meant to be used likely isn’t the best way to tackle the issue, goes the argument.

WATCH: Trudeau vague on details of proposed tax reforms

… Canadian private corporations as opposed to publicly traded and foreign corporations?

Critics of the reforms are also arguing that the government’s proposed fixes would put Canadian private corporations at a disadvantage compared to some of their competitors from a tax point of view.

“Public corporations and non-Canadian private corporations will be more favourably treated,” according to Mintz.

Many economists have long quibbled with Canada’s lower tax rate for small businesses, which pay 15 per cent on average in combined federal and provincial tax on corporate income compared to nearly 27 per cent for larger corporations.

The lower small-business tax rate applies only until companies reach $500,000 in income, creating an incentive for enterprises to stay small.

“Recent studies have shown that many small businesses are created here, but few actually grow. We’ll help if you’re small, but we make it hard for businesses to become stars,” Mintz wrote.

Switching to a single corporate tax would be a simpler way to fix many of the problems the Liberals are trying to tackle, he argues.

Tedds agrees: “If we get rid of the small-business rate then many of these problems are tempered.”

In general, economists on both sides of the debate worry that the tax fixes proposed by the government may be too convoluted.

READ MORE: Morneau draws criticism from business, concerns from Nova Scotia premier over tax proposal

Both Mintz and Milligan have expressed concerns about the potential complexity of the new rules.

… tax accountants?

Who cares about tax accountants, you may ask. Neither Canadians nor politicians seem particularly interested in their fate. But their situation tells us something about the potentially much broader impacts of the tax changes.

On the one hand, like doctors and lawyers, many of them operate as incorporated small businesses, which would make them potential losers from the reforms.

On the other hand, if new rules end up further complicating Canada’s tax system and encouraging ever more complex tax-planning strategies, they’re likely to see brisk business in coming years.

No offense to accountants, but if that happens, it will likely be a sign that the reforms failed.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.