The idea that parents are done supporting their children when they hit 20 or so may be headed for extinction.

You’d be hard pressed to find a starker indication of that than what’s happening at BlueShore Financial. The British Columbia-based credit union is renovating its head office and branches to expand its meeting rooms, which increasingly need to host large family discussions about finances.

READ MORE: Nearly half of Canadians count on inheritance for retirement — will they actually get any money?

It’s not just parents helping out their grown kids. Grandparents are stepping in, too, according to BlueShore president and CEO Chris Catliff.

In Vancouver, soaring housing prices have buoyed the net worth of seniors and boomers, while putting homeownership out of reach for many young adults.

READ MORE: Toronto could become a ‘buyer’s market’ in coming months: RBC

Often, it takes two families to join forces in order to help one young couple buy their first home. And that’s when one really starts to need a lot of chairs around the table, he told Global News.

Skyrocketing home prices have exacerbated the generational wealth divide in Vancouver and Toronto. But parents across the country are finding that their progeny needs a little extra oomph for financial takeoff.

Help usually comes via cash or free room and board.

The percentage of Canadians between the ages of 20 and 29 who are living at home with at least one parent stood at 42 per cent in 2011, up from 27 per cent in 1981, according to the latest available data from Statistics Canada.

And over the past year or so, some 18 per cent of first-time homebuyers used a gift from relatives for their down-payment, according to a recent survey by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation.

READ MORE: Time to stop shaming millennials for living with their parents, personal finance experts say

Even when real estate isn’t prohibitively expensive, young people need more schooling to find employment, pay more for education, and (despite all the schooling) take longer to land a good, steady job.

The notion of parents shoring up their grown children’s finances, though, remains largely a cultural taboo. Tell anyone you’re writing a monthly cheque to help your married child pay for utilities and you’re likely to hear that you’re a helicopter parent, unwitting enabler of a generation of spendthrift weaklings.

But families banding together across generations to make ends meet is far from a new phenomenon, historically. If anything, it’s a return to the past.

WATCH: Study says Canadian boomers less likely to leave an inheritance

The ‘bank of mom and dad’ has been around for a very long time

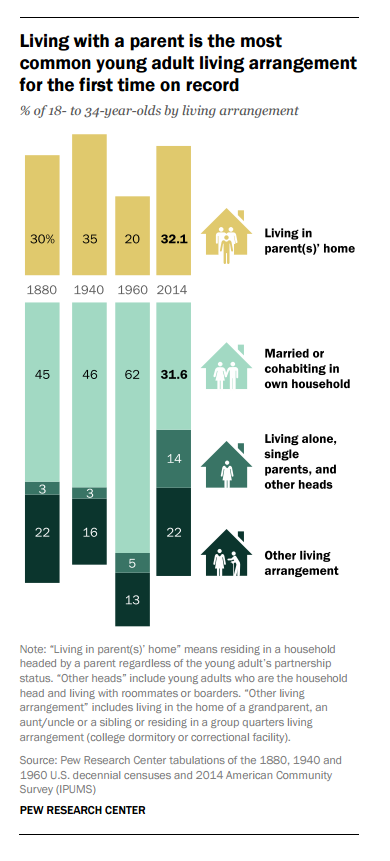

In the U.S., for example, the percentage of 18- to 34-year-olds who were living at home with their parents in 2014 (32 per cent) was in with rates seen in 1940 (35 per cent) and 1880 (30 per cent), a recent Pew Research Center study showed. In the report, it’s the 1960s that look like a historical aberration, with only 20 per cent of young adults rooming with their parents back then.

The post-war years are historically unique in other ways, the research shows. A whopping 62 per cent of adults under 35 were living in their own home with their spouse or partner in 1960. Today, that share is only 31 per cent. But the gap between today’s young Americans and older generations shrinks considerably when you look at 1940 and 1880, when only around 45 per cent of people aged 18 to 34 were living on their own with their significant other.

READ MORE: More young adults relying on ‘Bank of Mom and Dad’: study

And the post-war era was a period of economic — not just demographic — boom. The unemployment rate in 1965 was just 3.9 per cent in Canada, according to historical data. By contrast, the jobless rate today is hovering around 6.6 per cent — and that’s considered quite low by the standards of recent economic cycles. (The methodology for calculating the unemployment rate has been tweaked through the years, but readers will get an idea of the different realities faced by the two generations.)

READ MORE: The number of young Canadians going bankrupt is rising — but student debt isn’t the whole story

Since the mid-1970s though, wages haven’t really gone anywhere, with the average hourly pay stuck at the equivalent of $24-$25 in today’s dollars since then, according to Statistic Canada. And that’s despite the fact that young people today are more educated than they were some 40 years ago.

It might be that, in leaner economic times, families are — consciously or unconsciously — reverting to how things used to be.

WATCH: Is this what’s keeping millennials from buying a home?

Have a plan, set some rules, stop being ashamed about it

Parents today may find themselves channeling cash towards their adult children’s bank accounts, but they rarely planned on it, according to Investment Executive (IE) magazine.

By contrast, many immigrant families who expect their adult offspring to need help for a while, are more likely to have set conditions and expectations, according to the article.

READ MORE: Boomers willing to risk it all for ‘boomerang’ kids: report

“The key is to make sure you have enough for retirement,” said Harpreet Saroya, a financial adviser at BlueShore, and to be conservative in that calculation.

She advises clients to assume they’re going to live to age 95 or 100, factor in assisted-living — which can be pricey — and build in plenty of contingency funds to cover health-care costs.

If parents or grandparents want to borrow against their home to free up some cash for the kids, they should ensure they will continue to have lots of equity in their property even if prices drop in a housing downturn, she added.

They should also be aware that if they buy real estate for their child, that will become part of the family assets that a spouse can lay claim to if the marriage breaks apart.

That issue doesn’t arise with trusts, noted Saroya.

Still, real estate remains a very popular way for families to share wealth, at least in Vancouver, according to Catliff.

“We often see families buying investment condos with the idea that they could be used by the grandparents when they downsize, or the children when they’re in university — or for rental income,” he said. “It’s becoming a broader family asset, and that’s just fantastic.”

WATCH: Now more seniors than kids in Canada

Comments