At the start of a new year when, traditionally, the land is nestled in under a blanket of snow, a mostly barren southern Alberta is facing the prospect of another terrible drought.

John Pomeroy, University of Saskatchewan professor and Canada Research Chair in Water Resources and Climate Change, said last year’s drought conditions were the “worst of a lifetime” for many parts of Alberta.

And looking at the supply in rivers like the Bow River, agricultural regions heading towards Medicine Hat, and into the south of the province near Lethbridge, Pomeroy said the winter conditions are “incredibly dry and still dry.”

“These regions still don’t have snow cover. Soil moisture levels are less than 40 per cent of normal. The snowpacks have not built up this year,” he said. “And we know snow is how we got into trouble last year with the drought: the snowpacks were below normal and then they melted early.”

What’s got Pomeroy more concerned is the water storage levels across the province are very low right now.

“The reservoirs are extremely low in the mountains and the irrigation districts, soil moisture reserves are depleted in the agricultural regions and groundwater is starting to drop down. So we don’t have any reserves to fall back on if this drought continues.”

Environment and Climate Change Canada said last year was a dry year for Alberta, noting some areas received less than 45 per cent of normal precipitation. It was also the hottest for multiple cities in the province and top four for others, including in Calgary where last year marked the second-hottest on record.

The system of reservoirs and water supply systems could be replenished with an above normal snowpack this winter and a normal runoff in the spring.

But an El Nino year means we’re likely to see drier and warmer weather than normal this winter, and Pomeroy said we could see another rapid melting off of what snowpack accumulates, repeating 2023’s conditions.

“And also, remember we’re seeing climate change now. This is what it looks like,” Pomeroy said. “And so (drought conditions are) not going to go away after a bad year. We’re going to keep seeing these effects year on year. Alberta was over five degrees above normal in December. If we have those conditions in the spring again, then we’re back into an agricultural disaster.”

More water restrictions in Calgary?

At the end of July 2023, the City of Calgary introduced voluntary water restrictions to reduce demand on reservoirs.

Two weeks later, the city introduced the first stage of outdoor water restrictions, placing prohibitions on washing outdoor surfaces, washing vehicles outdoors, filling fountains or decorative features, and placing time restrictions on when lawns, trees and gardens could be watered. Those water restrictions were lifted at the end of October 2023, but conditions in the city remain classified as “dry,” like when restrictions were brought in five months ago.

Pomeroy called the water restrictions in Calgary “wise.” At the start of 2024, the city still asks that as it scales back water use for city operations, Calgarians use water wisely in their homes.

“Every drop counts as we prepare for another dry summer,” Nicole Newton, City of Calgary manager of natural environment and adaptation said in a statement. “Outdoor water restrictions are likely this summer. Many factors are considered before putting them in place like river flow, water use and current and predicted weather conditions.”

Get breaking National news

The city’s Drought Resilience Plan, published last year, said Calgary is situated in a place that is prone to prolonged periods of dry weather, and that climate change brings water-related hazards like floods, droughts and poor water quality. The city’s climate strategy names drought as one of the city’s eight main climate hazards, one that is likely to increase in frequency.

If conditions get worse than the summer and fall of 2023, the city could introduce further restrictions on lawn and garden watering, use of outdoor pools and water use for construction, among others.

Back to back dry years for ag?

For farmers in the counties surrounding Calgary, they’re hoping some winter precipitation will help set up their next growing season to be better than their last.

“This year we haven’t even seen a lot of snow and if we do get it seems like a chinook’s coming, it melts away,” Allen Jones of Jones Hereford Ranch in Balzac, Alta., said. “But our bigger problem is the spring runoff: the last two years, we haven’t seen any. And so our dugouts are really low now.”

Jones operates a 5,000-acre farm that includes 200 head of cattle. A lack of water in 2023 created production issues for the farm.

“Not enough forage for the cattle, pastures weren’t producing and that made it difficult to feed them.”

That puts a squeeze on his balance sheets, as his operating costs are unable to be balanced by production.

Established in 1903, Jones Hereford Ranch has seen more than a century of drought cycles. But with dugouts run dry heading into what could be a warm and dry 2024, things could get tough for the Albertan farmer.

“It’s going to make it damn tough because there’s just no reserves left, so I guess we’ll cross that bridge,” Jones said. “But, you know, at the end of the day, if you don’t have feed, you get to sell the cattle.”

Fires keep burning

Dry conditions make for ideal conditions for fires to start. Alberta Wildfire is already preparing for what could be another challenging wildfire season after a record-breaking 2023 that saw 2.2 million hectares of Alberta go up in smoke.

Wildfire officials are keeping a close eye on how much precipitation – snow and rain – comes before the spring.

“The biggest factor really influencing spring wildfire season is how much rain we get. But obviously precipitation in general is a big factor year round,” Christine Tucker said.

Despite the official end of the wildfire season being marked in the fall, there are still 64 fires burning throughout the province, about 10 times the normal amount.

“For us traditionally, we rely on that ice and snow and cold temperatures to really do the final work that our firefighters have been doing through spring, summer and fall to bring those fires under control and to extinguishment,” the Alberta Wildfire spokesperson said. “We haven’t seen that as much this year, which is why we’re coming into 2024 with so many wildfires still burning.”

Drought emergency plan

On Dec. 20, 2023, Environment and Protected Areas Minister Rebecca Schulz sent a letter to municipalities saying the province is one drought stage away from a provincewide emergency, and staff from her ministry and Agriculture and Irrigation ministry are meeting with water licence holders, major water users and others to develop water conservation plans and water-sharing agreements. Other work that has been completed by the drought command team is a preliminary drought emergency plan for 2024.

The letter asked municipalities to prepare for a possible drought by measuring water supply, reviewing terms of their water licences, develop a water shortage plan and prepare for the possibility of working with provincial officials if terms in their water licences are triggered.

“We are asking all water users to start planning now to use less water in 2024,” Schulz said in her letter.

In a statement to Global News, Schulz said there is a “high risk that conditions could worse this year” and is preparing for the possibility.

She said the province will be awarding a contract for drought modelling work in the coming weeks, to “help inform efforts to maximize the province’s water supply.” A drought advisory committee is also expected to be announced soon.

“Our province has navigated droughts before. We have a long, proud history of coming together during tough times, and we will get through this together,” Schulz said in the statement.

Continental drought

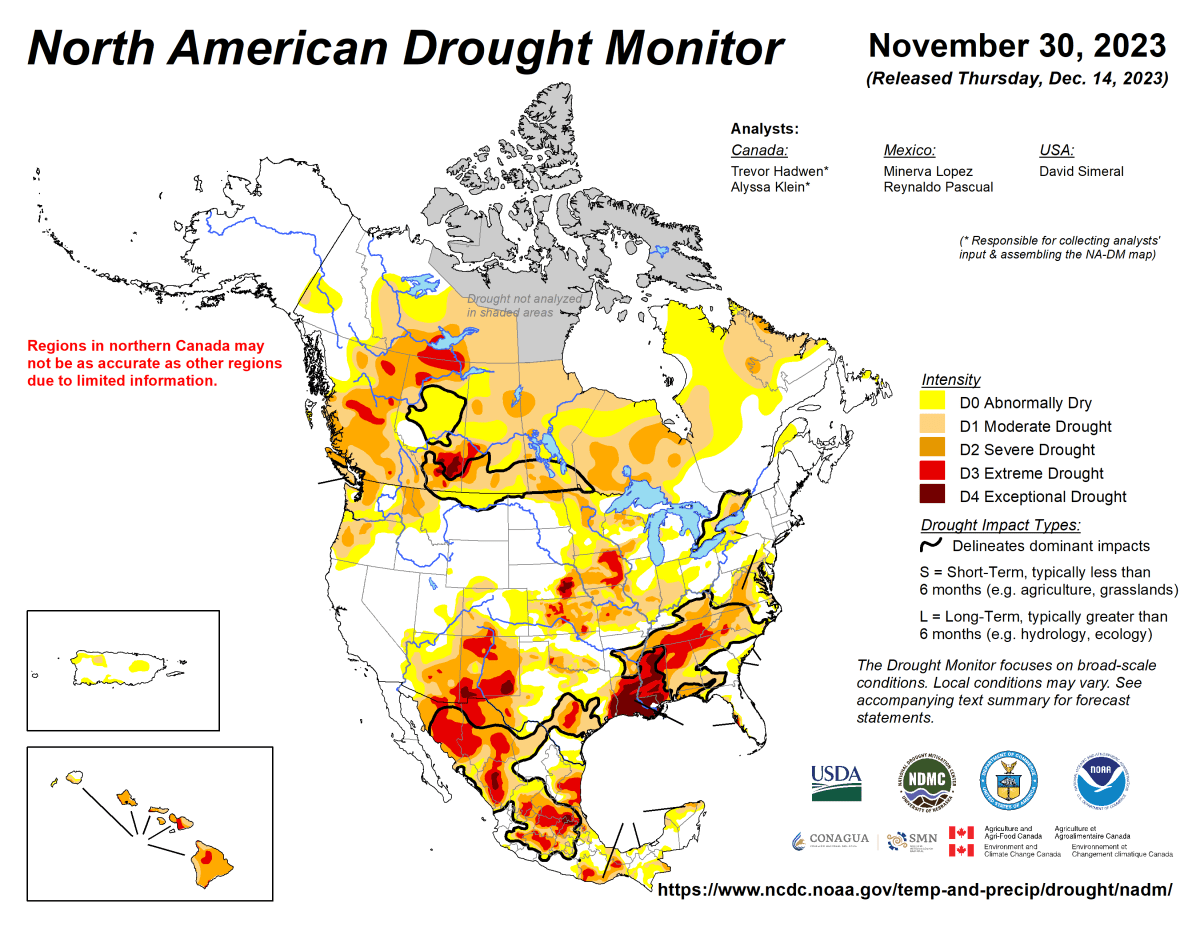

Alberta is not alone in its December drought conditions. According to the North American Drought Monitor, most of the continent is at least abnormally dry.

In the monitor’s latest readings, drought was observed in nearly 61 per cent of Canada, from coast to coast to coast, with only Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and P.E.I. not having droughts.

Droughts cover large swaths of the southern and midwest United States, as well as the Pacific northwest, with almost 47 per cent of that land mass at least abnormally dry.

Even the state of Hawaii is experiencing widespread drought.

Most of Mexico – almost 70 per cent – is under drought conditions.

“We’re seeing an exceptional situation and it’s a continental drought and it’s long lasting at this point. And its severity and extent is something that the combination is unprecedented to my experience,” said Pomeroy, whose hydrology experience dates back to the 1980s.

Groundwater is next

Pomeroy said if there’s no improvement in water levels across the province, he expects to see more water restrictions in place, like were implemented in Calgary.

“Other communities are in worse shape and Lethbridge is very, very concerned about being too able to supply drinking water to its residents next year, over this year. And many rural communities that rely on small surface water ponds are in dire trouble,” he said.

“Groundwater is the next one to be affected because it’s not getting the recharge that it normally would hold.”

Pomeroy said if the many reservoirs, irrigation canals, and other water supply systems aren’t refilled by snowpack melt and spring rains, it could mark a sea change in the province.

“It means we have to change how we manage water in Alberta.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.