Written communication among kids and teens today has morphed into such a confusing mixture of acronyms and emojis that it can almost make hieroglyphics more easily understood. This is why it’s important for parents to be up on the latest text slang.

“Text lingo practically changes weekly and a lot of the times, parents have no clue what their kids and their friends are saying,” says Titania Jordan, chief parent officer of Bark, a software program that monitors, detects and alerts parents to potentially dangerous conversations on their kids’ cellphones, and email and social media accounts.

READ MORE: How to teach your kids about online privacy

“I’m surprised at how many parents still don’t know what ‘Netflix and chill’ means.” (For the record, it refers to hooking up, not actually watching Netflix.)

Although surveillance software of this nature isn’t new, Bark differentiates itself by sifting through conversations and only alerting parents to troubling words or thoughts — ones whose acronyms parents might not be familiar with. Most of the other programs and apps will provide parents with all the data that goes through their kids’ devices, resulting in a lot of information to wade through.

It also has the ability to decipher when kids are kidding and when they’re being serious.

Jordan says that since its launch in 2016, Bark has received about 25 messages from parents thanking them for alerting them to their kids’ mental health issues, saying that it gave them the opportunity to get them help and ultimately save their lives. (You can sign up or download the app here. Rates are US$9 per month or $99 for a year, and the first month is free.)

- Buzz kill? Gen Z less interested in coffee than older Canadians, survey shows

- Indigo nears privatization but experts warn turnaround won’t be ‘quick fix’

- Toyotas, RVs and nearly 3K school buses: A list of vehicle recalls this week

- Canada updating sperm donor screening criteria for men who have sex with men

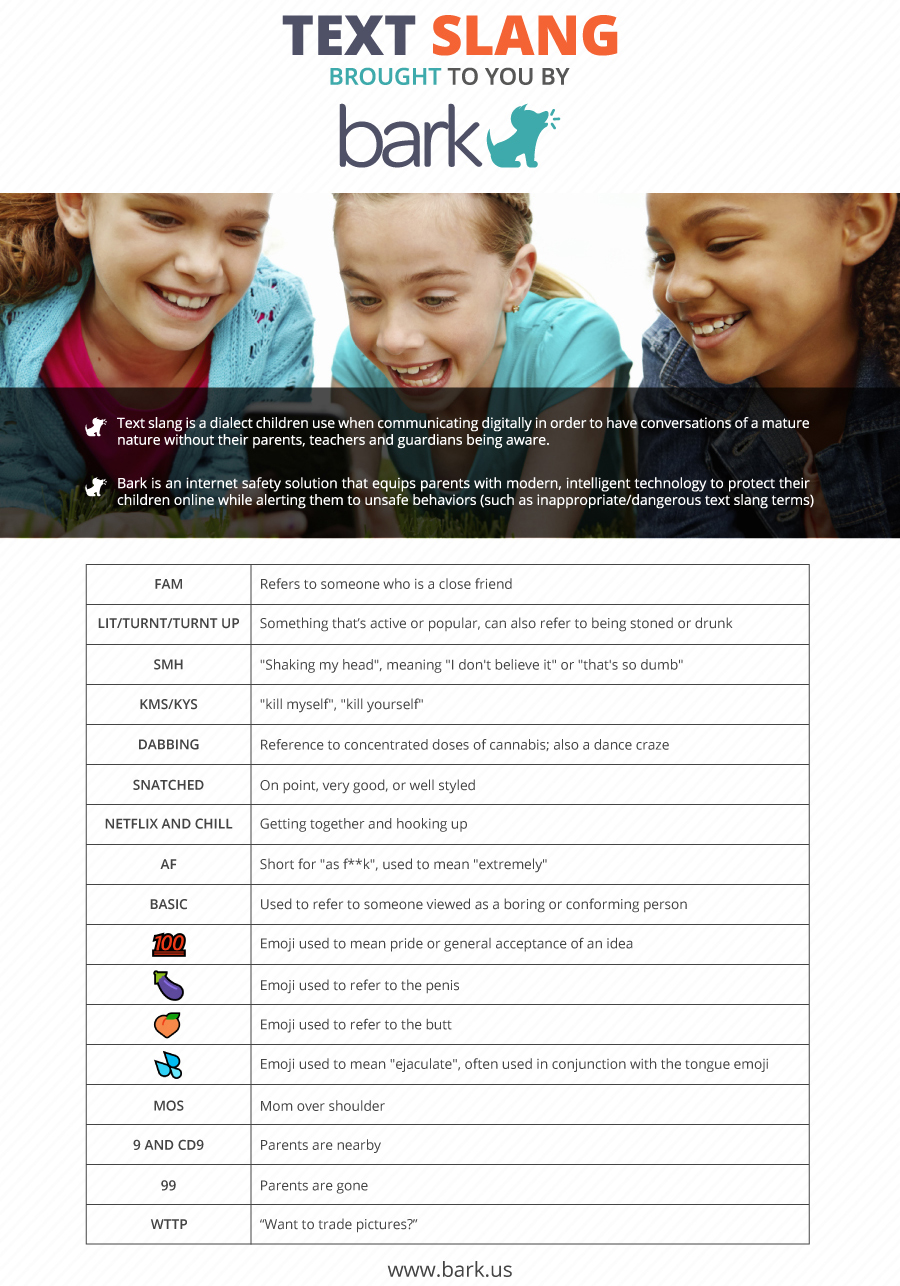

In addition to KMS/KYS (kill myself/kill yourself), other new acronyms that Jordan says parents should be aware of include:

GNOC: get naked on camera

FBOI: a guy who’s just looking for sex

WTTP: want to trade pictures

FINSTA: fake Instagram account

PAL: parents are listening

1174: meet at a party, stat

For older generations watching the proliferation of these surveillance programs from the sidelines, it can look like an invasion of privacy. But Vancouver-based parenting coach Julie Romanowski says it has become an expectation today.

“This is a non-negotiable point that parents have the right to be on top of,” she says. “Have an initial conversation about the guidelines and expectations you have about the device, and highlight what the child can and cannot do with it. A lot of parents assume their kids know what’s OK and what’s not.”

Romanowski also advises creating “check points,” regular conversations to observe and discuss what has been going on. By scheduling it, kids won’t feel like it’s been sprung on them and they’re less likely to become defensive.

Jordan echoes this idea: “This isn’t like the sex talk that you used to have only once. This is a conversation that should be happening every few weeks.”

She also advises parents to talk about what’s happening in their kids’ world, like new apps or stories about youth in the news that would be relevant to them. This will help them open up.

READ MORE: Looking for a unique baby name? These are the names that no one used in 2016

No one would be faulted for sifting through a young person’s text conversation and being utterly confused by it, so Romanowski advises parents to search unknown terms online, or ask a friend or colleague. But really, the source should be their own kid.

“The child should be the one explaining it when you ask,” she says. “If you tell them that this is one of the rules in the initial conversation, your child will better understand why you’re asking.”

Not that kids these days are taken off guard by these kinds of questions or expectations, Jordan says.

“In this day and age, kids are used to the fact that their parents are tech savvy and that they’ll be monitored, whether it’s with GPS apps or software that gives them access to their devices. There’s no argument about whether or not your parents should be informed.”

Comments