Two teams of scientists have independently created synthetic mouse embryos in a lab without using eggs or sperm cells in a major leap forward for the field of developmental and stem cell biology.

Scientists were able to nurture these embryos to form a brain, a beating heart and the foundations for all other organs in the body.

These man-made embryos could have massive implications for the future of medicine, as scientists seek to apply their findings to human embryos and use them to grow organs for transplant at a time when more than 4,000 Canadians are currently on a wait-list for organ donations. The recent advancements may also help researchers investigate what causes some pregnancies to fail and could help pinpoint specific genes that cause developmental disorders and birth defects.

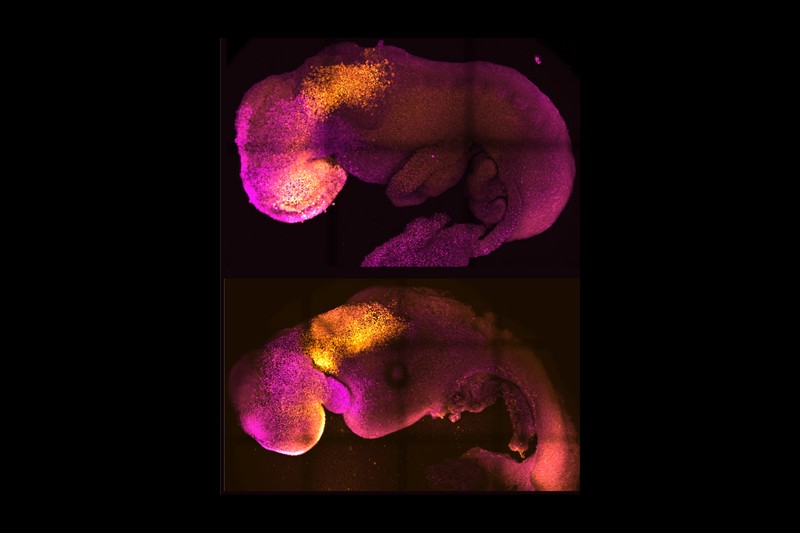

One of the teams behind this groundbreaking advancement was helmed by Prof. Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, a developmental biologist from the University of Cambridge. Her team used stem cells from a mouse to create a synthetic embryo that they were able to keep alive for 8.5 days, according to a Cambridge press release. Full mouse gestation takes about 20 days.

“Our mouse embryo model not only develops a brain, but also a beating heart, all the components that go on to make up the body,” Zernicka-Goetz said. “It’s just unbelievable that we’ve got this far. This has been the dream of our community for years, and a major focus of our work for a decade, and finally we’ve done it.”

The findings from Zernicka-Goetz’s team were published in Nature on Aug. 25 while a second team of researchers from Israel published similar results in Cell on Aug. 1.

How did they do it?

There are three types of stem cells responsible for the building blocks of life in mammals: one that will form body tissue, one that becomes the placenta, which connects the fetus to the mother to provide nutrients, and one that creates the yolk sac, where the embryo grows.

When Zernicka-Goetz and her team first started trying to develop man-made embryos they began with just one type of stem cell, the one that generates body tissue.

“We started with only embryonic stem cells,” she says. “They can mimic early stages of development, but we couldn’t take it any further.”

A few years later, her team found that if they added the stem cells responsible for the creation of the placenta and yolk sac, they could nurture their synthetic embryos to develop much further. When combined in the right environment, the stem cells self-organized into structures that mimicked the natural development of an embryo, creating a beating heart and the foundations for an entire brain.

Get weekly health news

Under normal circumstances, for a healthy embryo to form, all three types of stem cells must “talk” to each other to co-ordinate development. Researchers were able to kick-start that dialogue between the stem cells by placing them in specific proportions in a unique environment that encouraged interaction, both chemically and physically, between them.

Zernicka-Goetz’s team did this by using a technique that was created by Jacob Hanna, a stem cell biologist at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel. Hanna is also working on creating synthetic embryos and his team was behind the Aug. 1 study in Cell that generated similar results to Zernicka-Goetz’s team. Hanna is also listed as an author in the Aug. 25 Nature study.

Last year, Hanna’s team announced that they had created a machine that could culture natural mouse embryos outside of the uterus for an unprecedented amount of time, according to a press release from Nature. The machine rotates glass vials, which hold the embryos, on a Ferris wheel-like system and allows scientists to control the oxygen and carbon dioxide levels within.

Hanna shared the incubator machine with other biologists, including Zernicka-Goetz and her team, who tweaked it to fit with their experiments.

“The brain of this machine, we shared with everyone who asked for it,” Hanna said.

Hanna’s team was also able to grow synthetic mouse embryos for 8.5 days but they did not develop full brains like Zernicka-Goetz’s tests.

What we can learn from this

One benefit of being able to view an embryo outside of the uterus is that researchers can observe how stem cells communicate to develop a viable fetus. According to the University of Cambridge press release, many pregnancies fail around this time when the three types of stem cells responsible for embryonic development start to send signals to each other.

“So many pregnancies fail around this time, before most women realize they are pregnant,” Zernicka-Goetz said. “This period is the foundation for everything else that follows in pregnancy. If it goes wrong, the pregnancy will fail.”

“This period of human life is so mysterious, so to be able to see how it happens in a dish — to have access to these individual stem cells, to understand why so many pregnancies fail and how we might be able to prevent that from happening — is quite special,” Zernicka-Goetz continued. “We looked at the dialogue that has to happen between the different types of stem cell at that time — we’ve shown how it occurs and how it can go wrong.”

Not only can these synthetic embryos allow us to peek at how stem cells cause pregnancies to fail or succeed, but they can also show how specific genes impact development.

Zernicka-Goetz’s synthetic embryos are special because they were able to generate the foundations of an entire brain, allowing researchers to study how brain development can change in the presence or absence of certain genes.

“In fact, we demonstrate the proof of this principle in the paper by knocking out a gene already known to be essential for formation of the neural tube, precursor of the nervous system, and for brain and eye development. In the absence of this gene, the synthetic embryos show exactly the known defects in brain development as in an animal carrying this mutation,” Zernicka-Goetz said. “This means we can begin to apply this kind of approach to the many genes with unknown function in brain development.”

Investigating this field could help researchers better understand the origins of developmental disorders and birth defects, potentially making them preventable in the future.

And perhaps the most exciting development that can arise from these advancements in synthetic embryos is the possibility of creating organs for human transplantation.

The current research was carried out with mice but researchers are working to pivot to human embryos. Getting to the point of organ formation in a human embryo has never been done before and presents a significant challenge. But Ali Brivanlou, a developmental biologist at The Rockefeller University, who wasn’t involved in the two studies, said “the field is not too far away.”

“There are so many people around the world who wait for years for organ transplants,” said Zernicka-Goetz. “What makes our work so exciting is that the knowledge coming out of it could be used to grow correct synthetic human organs to save lives that are currently lost.”

Zernicka-Goetz also said it could be possible to heal already existing organs in adult humans with the knowledge that researchers gain from embryonic stem cell development.

Ethical concerns

As scientists can nurture these embryos further, potentially into fetuses or beyond, it raises major ethical concerns.

The International Society for Stem Cell Research previously cautioned against culturing human embryos past 14 days, though that recommendation has since been removed. Its guidelines now state that scientists creating embryos should have a compelling rationale behind their research and should use the minimum number of embryos necessary.

Researchers have been working on man-made embryos for years, but one scientist is concerned that, as advancements get us closer to developing organs, ethical backlash is bound to follow.

“The reaction to that could jeopardize this whole field of research,” said Martin Pera, a stem cell biologist at the Jackson Laboratory Center for Precision Genetics.

“It’s important that people know what is being proposed and that it’s done with some kind of ethical consensus,” Pera added. “We have to go cautiously.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.