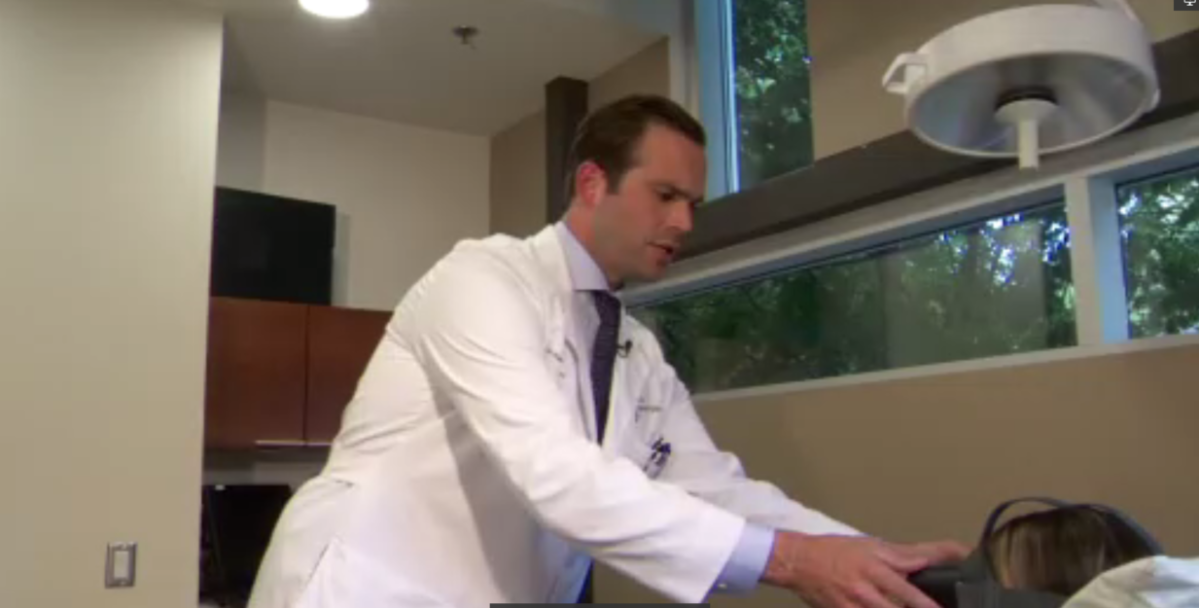

Plastic surgeon Dr. Ryan Austin prepares for a procedure by getting his patients comfortable. But instead of using drugs, he is offering a narcotic-free alternative: virtual reality (VR).

“It allows them to have the procedure done … safely without going to sleep,” Austin, who runs a clinic in Mississauga, Ont., told Global News. “There is risk associated with a general anesthetic and then it allows them to quell that anxiety.”

Having patients wear a virtual reality headset during more minor procedures such as mass removal or hand surgery, has shown a real improvement in patient pain as well, Austin says.

“Some of these procedures can be very short … 10 or 15 minutes, while others can be very long…one or two hours,” Austin explained. “They feel less soreness because they have something to distract them while the procedure is going on.”

Austin has only been using the headset at his clinic for a couple of months. He said there are advancements to be made, but wants to see VR become a standard option during surgery.

Health Canada approved an all-in-one virtual reality software, SieVRt, for use in diagnostic radiology last summer. But the technology hasn’t been approved to help with acute or chronic pain.

When asked if the department is looking at approving VR devices for acute or chronic pain, Health Canada said in a statement it had not received any submissions for that specific use.

It did say, however, that it has authorized three clinical trials to date that are considering the use of VR devices for pain management therapies, “such as in rehabilitation, or the treatment of chronic pain.”

The agency previously told Global News that use of VR by physicians falls under the “practice of medicine,” which differs per province and territory.

What is virtual reality?

Virtual reality or a similar technology as we know today was developed in the 1950s and 60s, but it wasn’t until 1987 the term “virtual reality” was born.

VR refers to computer generated imagery and hardware specifically designed to immerse us into whatever scene we choose.

Get weekly health news

While Austin isn’t alone in using the technology for medical purposes, it’s not a common practice yet. North America dominates the augmented reality (AG) and VR heath sphere with the EU not far behind.

In November 2021, the U.S. FDA approved the first VR device for medical use with chronic lower back pain in patients 18 years and older.

Technology most commonly used today includes a headset and a tablet. There’s even sound and systems that monitor breathing. Patients are given the headsets and transported into 3D worlds such as a calming nature walk, ocean exploration or Cirque du Soleil show.

Dr. James Clarkson, an assistant professor of surgery at Michigan State, has been preforming “awake” surgical hand procedures assisted by VR since 2006.

“We found it’s those patients, about 30 per cent of them, that have an anxiety disorder that give us the highest reduction in anxiety, the greatest joy scores. And they also report less pain,” he told Global News.

- Ontario government home care vendor paid ransom to regain access to its servers: report

- Concerns over capacity at Vernon hospital psych ward after young man’s death

- Manitoba government proposes health charter but Opposition questions effectiveness

- Nova Scotia only faith-based hospital to end religious sponsorship

VR and pain management

Clarkson’s findings aren’t unique.

A large-scale data analysis from 2019 revealed most studies showed “VR helped to decrease acute pain during and immediately after various medical procedures.”

In May, a review of 1,430 studies found: “VR not only has applications in acute pain management but also in chronic pain settings.”

However, researchers in B.C. found that the use of virtual reality reduced procedure times but not pain or anxiety in awake pediatric plastic surgery patients aged six to 16.

While the “distraction” theory is the most popular means of explaining why VR is successful as a pain management tool, the reason for its impact on pain isn’t fully understood. That leaves a very important question unanswered: Could VR actually replace opioids?

Experts say more research is needed.

“I think that as the technology continues to improve, we’re going to continue to see advances,” said Austin.

At the University of Calgary, Dr. Linda Carlson and her team are in the initial phases of a study to determine how VR stacks up against pharmaceuticals.

“You only have so much mental capacity to pay attention to incoming signals. So you’re engaged and it downplays or dampens the pain signals that you might have been getting,” said Dr. Carlson.

Researchers aim to follow 20 people living with chronic pain related to cancer treatments who have tried different approaches to manage their pain. Over six weeks, they will be offered VR-based on mindfulness and relaxation.

“If we can show (a) larger, well-designed clinical trial and perhaps even compare it head on with medications to look at the efficacy…then it could be approved (by Health Canada),” said Carlson.

With the high risks associated with opioids and general anesthesia, especially in elderly populations, Clarkson wants to see the use of virtual reality become more mainstream in the medical community.

“We’ve been relying on Edwardian technology to give people surgery now for over 100 years,” he said. “We need to learn to change our approach.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.