EDITOR’S NOTE: This story has been updated to note that the Interpol Red Notice regarding Wang Zhenhua was rescinded on May 21, 2021, and that certificates of no convictions for Wang and his wife, Yan Chungxiang, were filed in Federal Court.

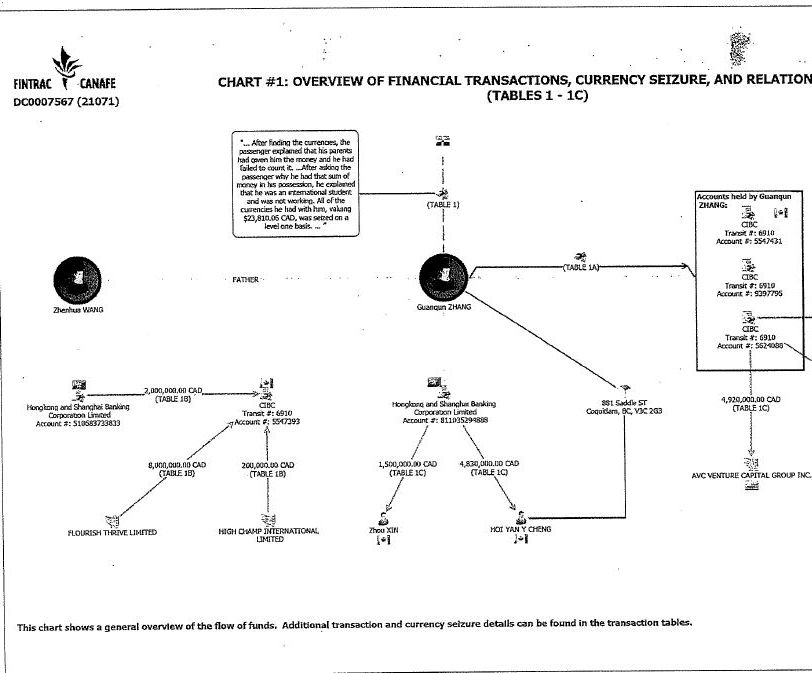

In August 2012, a 19-year-old student from Guangdong arrived from the Dominican Republic to Montreal with $23,800 in euros and U.S. dollars stuffed into his backpack. Four months later, Zhang Guanqun purchased an 8,500-square-foot mansion in Coquitlam, B.C., for $2.1 million.

It was only one of Zhang’s many multimillion-dollar transactions while attending Coquitlam College. From about 2012 to 2015, Zhang would funnel at least $33.75 million in electronic funds and cash through Canadian and Hong Kong bank accounts.

As it turned out, however, the Canada Border Services Agency and Fintrac, Canada’s anti-money laundering watchdog, had long been monitoring Zhang’s movements. They watched his parents, too. While living in Markham, Ont., they were wanted in China for allegedly defrauding 60,000 investors of about $200 million in a pyramid scheme, according to filings in a Federal Court case involving a refugee claim by the parents.

The filings by CBSA and Fintrac, whose accusations were not ruled on by the court, reveal details of the complex investigation. Zhang, now 28, successfully fought a deportation case based on CBSA accusations that he was involved in money laundering schemes and transnational organized crime.

“The amount of funds that Zhang has been involved in receiving and transferring wire transfers is truly astonishing,” an October 2015 forensic accounting report filed with the court in CBSA’s case states.

“The currency transactions were larger than one would expect, from an unemployed student.”

Over 600 pages in the CBSA filing mostly focus on Zhang and related cases against his parents, Wang Zhenhua and Yan Chungxiang. The couple arrived in Canada six months after Zhang landed in Vancouver, and right away, according to Fintrac records also filed in the Federal Court proceedings, they appeared to be using real estate, shell companies and foreign citizens in elaborate steps of money laundering.

“The following activity raises red flags for layering (a type of money laundering) and potential tax evasion because of a high volume of wire transfers from a foreign jurisdiction and from different individuals were received,” one Fintrac report on Wang and Yan said.

CBSA and Fintrac also found it suspicious that Yan Chungxiang and Wang Zhenhua — who also went by the Dominican name of “Antonio” — used a number of aliases.

CBSA’s files names dozens of people in China, Canadian law firms, a prominent federal Liberal Party organizer and even a Dominican Republic official in the country’s visa renewal department. They also outline a much broader concern of capital flight from China and secretive offshore banking routes through Hong Kong and Caribbean tax havens, which allow corruption suspects to spirit their gains abroad, buy passports of convenience, and hide dirty money in Canadian real estate.

The CBSA files provide a rare glimpse into an opaque business model increasingly cited in examinations of Canadian real estate, in which relatives use foreign students as fronts to funnel wealth into condos and mansions.

Evidence in B.C.’s current inquiry into money laundering, the Cullen Commission, asserts the occupation of “student” is often used to buy luxury real-estate in B.C. In one example, commission lawyers found that a landowner in China accused of bribery — now facing deportation hearings in Vancouver — had transferred at least $114 million from a Chinese province into British Columbia through Hong Kong currency exchanges with links to organized crime.

The man and his family members — whose identities were redacted in Cullen Commission documents — bought at least $30-million worth of B.C. property, and the corruption suspect’s daughter bought a $14-million Vancouver mansion, listing her occupation on the land title as “student.”

A leaked June 2008 Bank of China report, cited by the Cullen Commission, draws the same conclusion. A study on “Methods of Transferring Assets Outside of China by Chinese Corruptors” suggests that offenders ask relatives, especially their children, to study or work in the places where they live. They also use students to buy “immovable assets” including homes.

(Critics have noted assertions on corruption from Chinese state-owned entities and regulators sometimes need to be viewed with caution, because the Chinese state often uses its justice system for political objectives.)

Transparency International Canada, the anti-corruption watchdog, has studied luxury real estate trends in Vancouver, and finds that “student” buyers were a significant concern. Executive director James Cohen, who scanned some of the Guanqun Zhang case files obtained by Global News, said “this is a case study pointing to a model we have been red-flagging for a while now.”

Money trail starts near Beijing

In February 2011, from their office in Tianjin, a port city near Beijing, Zhang’s parents, Wang Zhenhua and Yan Chungxiang, started an investment and consulting company, Yingxin Equity Investment, and began raising funds.

But within months an investor complained to police, according to a case summary from China’s Public Security Bureau (PSB), filed in the Federal Court proceedings by CBSA, and in September 2011 police started probing suspicions that Yingxin was a pyramid scheme. One month later, Yan travelled from Shenzhen to Hong Kong. And in December 2011, police arrested Wang Zhenhua on allegations he fraudulently “seduced” thousands of Chinese citizens to invest in Yingxin Equity.

Wang, a tall man, uncharitably described as “fat” in PSB reports, was released on bail in January 2012, and travelled to Hong Kong. It was Wang’s first step, alleged in an Interpol Red Notice, in “absconding” to Canada. The Interpol notice was rescinded on May 21, 2021.

Get breaking National news

In April 2012, their son landed at the Vancouver airport, presenting an international student visa. He had briefly studied at a Catholic high school in New Jersey, and was then set to study at Coquitlam College. In this suburb just east of Vancouver, he purchased a mountainside mansion — complete with six bedrooms and seven bathrooms — with more than $2 million.

And immediately after Zhang landed, in the space of about 14 weeks, the student received at least $10.2 million from companies controlled by his parents in Singapore and Hong Kong. His parents would soon follow him to Canada.

Federal court records indicate that the couple arrived in September 2012, entering with visas issued by the Canadian embassy in the Dominican Republic. In the same month, back in Wang’s home province of Jilin, one of his co-accused was sentenced to four years in prison “for participating in Yingxin Company’s pyramid selling activities,” PSB documents indicate.

Wang and Yan resided in Markham, Ont., where they set up a company called MixCulture Capital with a local couple from China.

MixCulture’s mission was unclear. On one hand, it purported to promote tourism through the celebration of Chinese, Canadian and Dominican traditions. It was also described as an investment fund for a $5.3-million parcel of properties purchased by Wang and Yan in Tweed, Ont., a bucolic setting south of Algonquin Park. In another iteration, it was supposed to be a currency exchange and money transfer business, according to Ontario civil court records in a case where Wang and Yan claimed to have been defrauded.

But when relations between MixCulture’s directors went sour in late 2013, according to CBSA filings, one of the directors, Chen Xi, reported to York Regional Police that Wang and Yan had transferred from $40 to $50 million to their son, and Chen alleged the funds involved “fraud and money laundering.”

Fintrac filings show that also in late 2013, Zhang Guanqun started wiring massive funds out of his accounts, completing $17.5 million in transfers in four months, to accounts in Hong Kong, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Markham and Vancouver.

Meanwhile, CBSA flagged transactions between MixCulture and Glenis Guzman, a Dominican Republic official responsible for visa renewals at the country’s embassy in Ottawa. A Fintrac suspicious transaction report says that in November 2013, Guzman was wired $20,000 from MixCulture.

The official immediately attempted to withdraw US$20,000 cash, the report says, telling her Bank of Montreal branch she needed to send the funds to the Dominican Republic. Instead, the branch provided Guzman a US$20,000 bank draft, payable to an Ottawa currency exchange.

An investigation connected the funds from MixCulture to fraud, and since Guzman moved the funds through her account with complex steps that appeared to be a money laundering technique known as “layering” — a Fintrac report filed in court named her as a suspect in washing MixCulture’s proceeds.

Ontario court records show that Wang and Yan obtained temporary resident visas for Canada in the Dominican Republic in September 2013, and that they arrived in Canada on November 30, 2013, two days after MixCulture transferred US$20,000 to Guzman’s accounts.

In response to questions from Global News on the case, the Dominican Republic stated: “Mrs. Guzmán Felipe concluded her posting at the Embassy of the Dominican Republic in Canada in July 2018, therefore we will forward your message to the Department of Legal Affairs of our Ministry of Foreign Affairs to open an investigation on this matter.”

According to the Fintrac filings, Wang and Yan set up multiple Canadian bank accounts, informing bankers they were real estate tycoons with decades of experience in China. And they purchased at least seven properties in Ontario alone.

The Fintrac records also say MixCulture, its directors, and Guanqun Zhang were involved in $86-million worth of Canadian transactions. Wang — the father — received 29 wire transfers from 29 different Chinese people to an HSBC account, in several days.

All the transactions were related to students, and purportedly to fund tuition, travel and living expenses. In another Fintrac report, investigators noted it was highly unusual that Wang received 200 wire transfers to his CIBC account from dozens of different people in China.

As CBSA watched with mounting suspicion, they hired a forensic accountant to audit Zhang’s banking.

In October 2015, the report, filed in the Federal Court proceedings, concluded Zhang’s purchase of a $2.1-million home in Coquitlam, which he sold for $1.9 million in under two years, was “highly suspicious, and could be considered an attempt to integrate funds which he had received from his parents.”

It was one of at least five properties Zhang purchased in B.C., including a mansion in Richmond that Zhang bought for $3.15 million, land titles filed in Federal Court show.

The accountant also found that Zhang’s transfers of $4.9 million to a British Virgin Islands-registered company appeared to be “smurfing” — a money-laundering technique “often used to break up the amount of cash deposit into smaller amounts to avoid government reporting requirements or reduce suspicion at the local bank,” the report said.

Fintrac also flagged another transfer: $4.5 million to a company in Barbados, ranked among the world’s top-15 countries for suspected money-laundering transfers.

CBSA’s forensic analysis spotlighted several other people involved in Zhang’s transfers. One was a Saint Kitts lawyer named Fitzroy Eddy, who received a US$10,387 wire transfer from Zhang’s CIBC account. Online records in the “Paradise Papers” — a database of leaked records related to offshore banking — show a man named Fitzroy Eddy providing offshore trust account and immigration-investment services. The address from the papers shows up on Zhang’s wire transfer.

Eddy did not respond to emails and phone calls requesting comment from Global News.

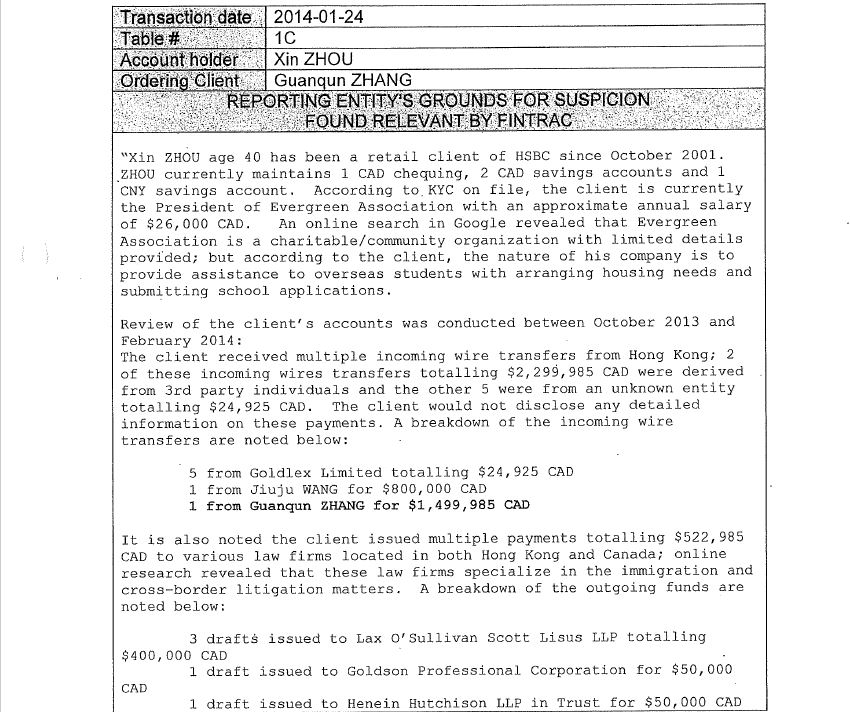

The accountant also zeroed in on a relationship between Zhang Guanqun, a “businessman” from Shenzhen named Jiuju Wang who banked in Hong Kong, and Xin (Richard) Zhou of Thornhill, Ont.

At the time, Xin Zhou was on the payroll of Ontario’s provincial Legislative Assembly as a “community outreach” official under the government of former Ontario Liberal premier Kathleen Wynne, a Fintrac report says. A Fintrac disclosure adds that Zhou’s reported annual salary in Canada was $26,000.

In 2014, Zhou was also fundraising co-chair for the federal Liberal Party, his LinkedIn profile says. Zhou briefly rose to prominence as a pivotal community organizer for Justin Trudeau’s 2016 campaign. In a few months, from 2013 to early 2014, Guanqun Zhang sent $2,999,985 to Richard Zhou. He also wired $6.3 million to Jiuju Wang in Hong Kong. And Jiuju Wang sent Zhou $800,000 from Hong Kong.

A Fintrac suspicious transaction report found Richard Zhou’s “account activity is inconsistent with customer’s stated occupation … (and Zhou’s bank) was unable to ascertain source of funds, (of) incoming and outgoing wires to unknown third parties and business entities.”

Fintrac also flagged $522,985 coming from Zhou’s accounts to a number of immigration and litigation law firms.

According to Fintrac, these incoming and outgoing transactions raised suspicions, but when Zhou’s bank asked him to explain “he refused to provide details or his relationship to the remitters.”

When Zhou’s bank pressed him on “the source of the incoming wires,” he explained that “the nature of his business is to provide assistance to overseas students with arranging housing needs and school applications.” The court did not rule on the allegations regarding Zhou. Zhou has not yet responded to multiple requests for comment from Global News on email and phone.

Since CBSA detained them in 2014, Wang Zhenhua and Yan Chungxiang have fought deportation, including filing a civil case that accused unidentified CBSA officers of wrongdoing. Court filings show from 2015 to 2018, agents searched and questioned Zhang whenever he re-entered Canada.

In March 2016, Zhang returned from a shopping trip in Washington state, and a CBSA officer reported that his phone texts showed that he had bought a condo for $366,000 in Richmond, just outside Vancouver, using a local lawyer. When Zhang returned to Vancouver from Hawaii two months later, a search of his phone showed he had recently purchased 2,000 shares of the Canadian pharmaceutical company Valeant, in a $168,000 transaction.

Lorne Waldman, who represented Wang and Yan in their refugee claim, said he no longer represents the couple and he could not comment on their case or point to another representative for them. Global News could not get a response from three other lawyers that have represented the couple.

From 2016 to 2018 Fintrac continued to watch Zhang closely, reports show, flagging $7.29 million worth of transactions, in 27 electronic fund transfer reports and one suspicious transaction report. In 2018, CBSA prepared an inadmissibility report against Zhang which was referred to the Immigration and Refugee Board for deportation.

In response to questions from Global News, Guanqun Zhang’s immigration lawyer Lawrence Wong noted that in July 2021, a federal court judge set aside Public Safety Canada’s decision to send Zhang to an admissibility hearing on money-laundering suspicions. The decision granted Zhang a judicial review of CBSA’s case, noting among other things, a certificate of no convictions for his parents, and did not rule on Fintrac’s allegations.

Wong, who was asked to comment on Fintrac records regarding Zhang and connecting his client to Richard Zhou and others named in the transaction reports, disputed Fintrac’s evidence as disputed and inaccurate.

“Fintrac documents appear to be your principal source and they are pure unsourced hearsay,” a lawyer responding for Wong stated. “They were given no weight by the Federal Court and after the Federal Court set aside the Minister’s Delegate referral; the Minister’s Delegate decided not to do another referral by closing its file. The court’s decision has brought the process to an end.”

In a response, Fintrac would not answer specific questions about its reporting in the Zhang case, but stated, “Fintrac’s financial intelligence is accurate and valued by Canada’s law enforcement and national security agencies.”

CBSA said it would not comment about ongoing cases.

But according to Clarence Lo, the CBSA officer who concluded the allegations Zhang was engaged in money laundering were sufficiently well-founded to refer to the Immigration and Refugee Board, the case boils down to whether the international student was “merely” following his parents’ directions, or knew what he was doing, while “actively involved in the receiving or transferring since his arrival in Canada (of) tens of millions of dollars.”

“The numbers on the Fintrac reports are hard to ignore,” Lo wrote in his December 2017 deportation recommendation. “It takes a fairly smart individual with financial savvy to complete that many wire transfers of substantial amounts over a long period of time.”

Comments