COVID-19 cases rose as Canadians spent more time outside their homes over the past year, but warmer weather saw lower growth rates of infections, according to a new study that tracked people’s movement using cell phone data.

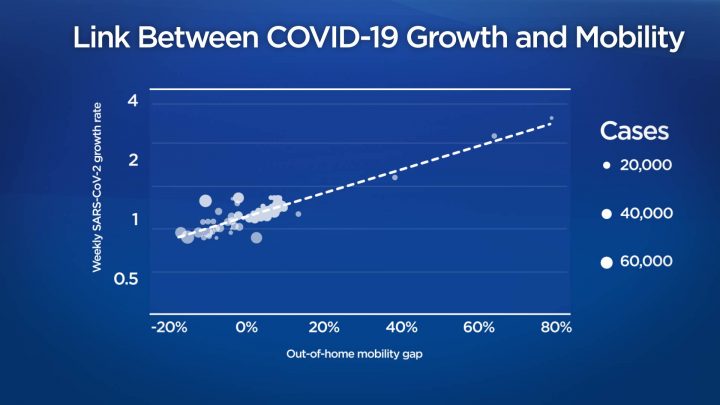

Peer-reviewed research published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal (CMAJ) on Wednesday showed that a 10 per cent increase in the mobility of Canadians outside their homes was associated with a 25 per cent jump in the weekly growth rates of COVID-19.

As most of the country grapples with a third COVID-19 wave and new variants, low levels of mobility are needed to control the coronavirus through the spring season, the study authors said.

“Overall, to stop the case growth, you need stricter measures of mass mobility in really highly urbanized places like Quebec and Ontario compared to the other provinces,” said Jean-Paul Soucy, an epidemiology PhD student at the University of Toronto and co-author of the study.

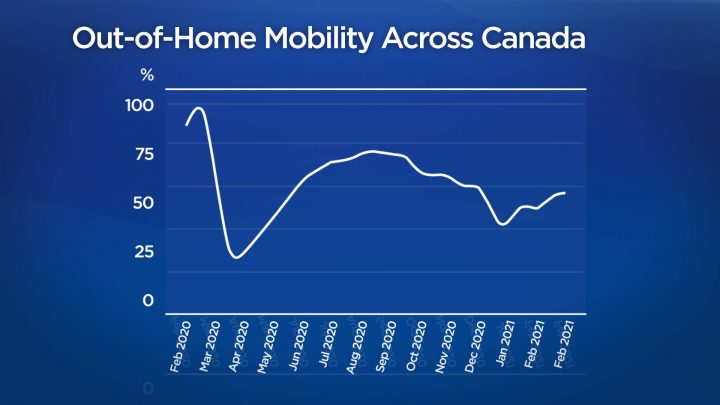

Between March 15, 2020, to March 6, 2021, researchers analyzed anonymized smartphone data from Google’s open-source mobility report which is updated daily and is based on users’ phone location services.

Get weekly health news

They looked at the mobility threshold, which is the level needed to control the coronavirus, and its difference compared to people’s actual movement — something called the mobility gap.

“We saw this really strong link between mobility and COVID-19 growth,” said Kevin Brown, lead author of the study and scientist at Public Health Ontario.

COVID-19 was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11 last year.

Canada swiftly closed its borders to non-essential international travel on March 16.

As provinces tightened restrictions, the movement of Canadians outside their homes dropped rapidly and reached its lowest level in April.

Warmer weather in the summer months saw lower levels of COVID-19 compared to the fall and winter season, even though people were moving around much more amid easing of lockdown measures, the study found.

“During summer, you saw a lot more people spent time in parks and outdoors rather than indoors where we know the transmission is much more likely to happen,” Soucy said.

“If a larger fraction of the time that’s spent out of the home is spent in parks — which happens during spring and summer, more so than in winter — then you can have that higher level of mobility and have a lesser effect on cases,” he added.

Amid a rise in cases and hospitalizations, several provinces have recently tightened restrictions.

A stay-at-home order went into effect in Ontario on Thursday after a provincewide “shutdown” was announced last week.

Meanwhile, several municipalities in Quebec are under lockdown with schools and non-essential businesses closed.

In British Columbia, a three-week circuit breaker went into effect on March 30. All indoor exercise classes have been cancelled and restaurants, pubs and bars closed to indoor dining.

Researchers say their data can help influence decision-making by public health officials and provincial governments related to COVID-19 restrictions.

“You want to be able to control COVID-19 without having these really strict restrictions on people moving around and people getting together,” Soucy said.

The data can also serve as an “early warning signal” to better guide public health interventions ahead of time, Brown added.

“It gives you a couple of weeks of additional time window that you’ll see mobility drop below the threshold before you see the reaction actually in case growth, because case growth really lags mobility by around 10 to 15 days or so,” Brown said.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.