As Canada continues to fight the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, western provinces could see a wildfire season that’s “well above average,” according to scientists with the federal government.

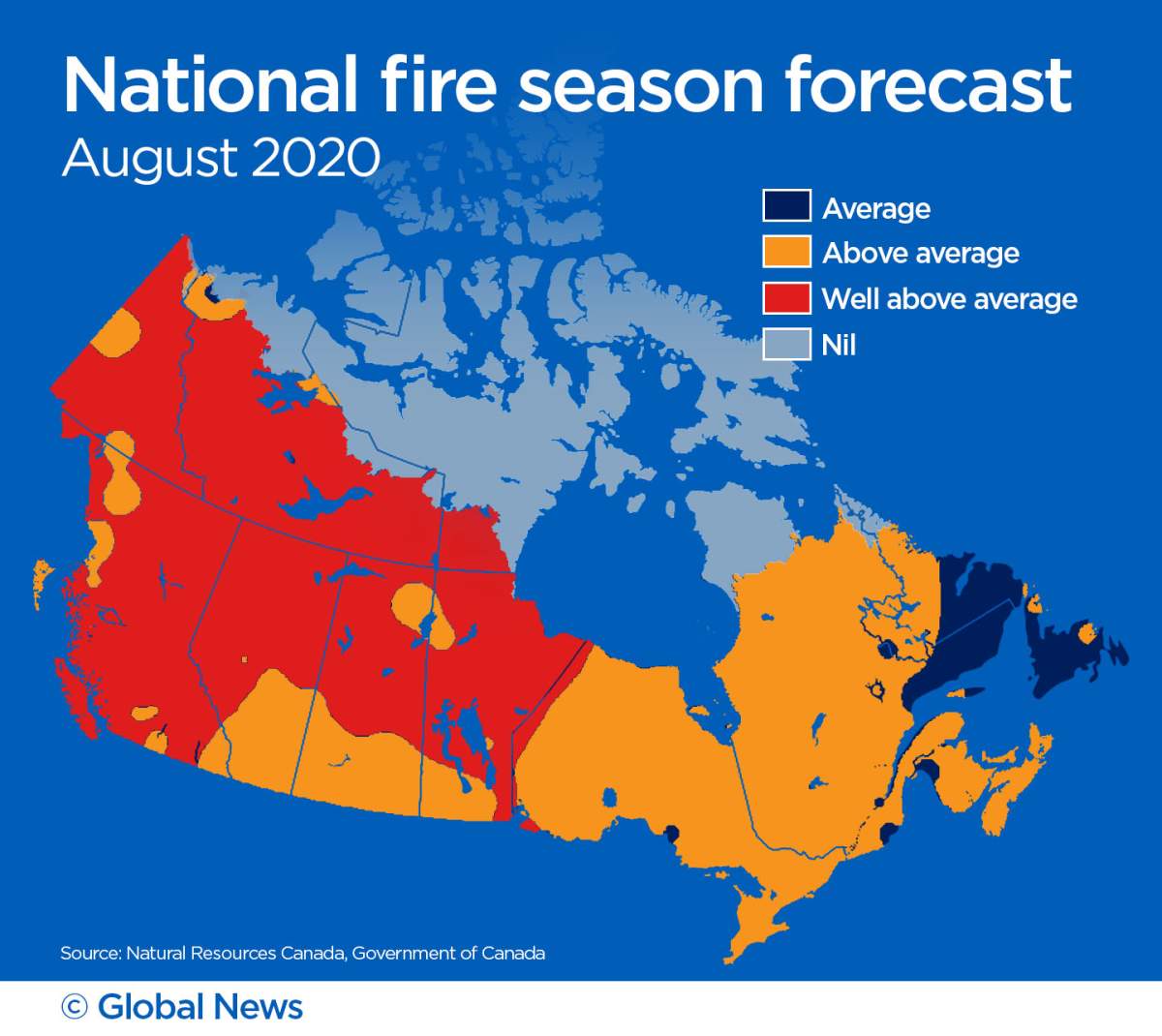

Natural Resources Canada has released new projections showing an elevated fire risk starting in June from B.C. to Northern Ontario and the territories.

Parts of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and B.C. could see an elevated threat of wildfires that stretches into September.

Bruce Macnab, the head of wildland fire information systems for the Northern Forestry Centre, said while at least one province now faces a “significant challenge” from wildfires every year, 2020 could see that threat spread across borders.

“It’s suggesting we’re going to have a fairly active fire season in Canada,” he said.

Macnab said the models aren’t necessarily predicting fire behaviour, but they do show how weather and climate conditions could play a role in prolonging or elevating the wildfire risk.

The news comes as a grim reminder for Alberta, as residents in Fort McMurray just marked the anniversary of a historic evacuation in the northern Alberta city four years ago.

The fire, which started May 1, 2016, ignited a massive blaze that tore across the area and saw more than 80,000 people flee their homes as flames created apocalyptic scenes along the highway out of the city.

The fire devastated the community and destroyed more than 2,600 homes and buildings.

Parts of B.C. are also still recovering the record-setting 2018 wildfire season, when hundreds of fires burned more than 1.3 million hectares of land. The season broke the record held by the one just before it, in 2017.

Provinces will now have to figure out how to fight fires and handle evacuations without spreading coronavirus, which has killed more than 3,800 Canadians and led to governments deploying massive amounts of resources to battle the health and economic repercussions of the pandemic.

Get weekly health news

Physical distancing measures imposed by governments across the country have also complicated how firefighters will be housed and transported when travelling to regions affected by fires.

But air pollution experts are also concerned that sustained wildfire smoke could further put people at risk of contracting COVID-19.

Sarah Henderson, a senior scientist at the B.C. Centre for Disease Control and an associate professor at the University of British Columbia, said air pollution can lower people’s immune system and make them more susceptible to infectious diseases.

“Someone who’s exposed to wildfire smoke, and then also exposed to the novel coronavirus, may become infected when otherwise they would not become infected … and the infection may be more severe than if the wildfire smoke wasn’t around,” she said.

Henderson said she and other scientists have been able to draw on precedent while researching the connection.

“During the SARS epidemic in China, there were more infections and more serious infections in parts of China that had more air pollution,” she said.

“We also know from other studies that wood smoke specifically … acts poorly with influenza and other respiratory illnesses.”

A Harvard University study that drew on nationwide data in the U.S. found that even a small increase in air pollution levels lead to a higher death rate from COVID-19. Henderson said other preliminary data has found that COVID-19 cases have been somewhat “protected” in areas with lower air pollution levels.

The 2018 B.C. wildfire season saw a surge in emergency room visits due to shortness of breath believed to be caused by weeks of lingering wildfire smoke, which also set records.

The smoke got so bad that year that Vancouver’s air quality was briefly ranked the fifth worst among the world’s major cities by the World Air Quality Index.

Yet health officials assured that there would be no long-term health effects due to the smoke, which is not as harmful to the lungs or other organs as cigarette smoke or vehicle exhaust.

But with the threat of COVID-19 added to the equation, Henderson is urging long-term care homes and other seniors’ facilities in particular to ensure their air is filtered properly.

“It’s something that should be considered now, rather than later,” she said, including determining whether rooms should be individually air cleaned during the wildfire season.

Henderson added that physical distancing measures could also impact how evacuees are sheltered if wildfires threaten communities.

Alberta, which saw over one million acres burned by wildfires last year, has already taken steps prepare for a more active wildfire season. Premier Jason Kenney’s government announced a fire ban last month that covers most of the province, as well as restrictions on off-road vehicle use, hiring more firefighters and additional funds for prevention programs such as FireSmart.

Alberta’s Minister of Agriculture and Forestry Devin Dreeshen called the bans “unprecedented steps” at the start of wildfire season, which started on March 1, one month earlier than any other province.

“Do your part in preventing human-caused wildfires,” Dreeshen said. “We don’t need the added burden of a human-caused wildfire.”

Ontario has banned fires outright through its entire fire region, while British Columbia is banning fires larger than an average campfire.

Macnab said the final outcome of this year’s fire season will depend on how people follow those burn bans, and how mindful they are of their own potential to start a wildfire.

That includes everything from properly disposing cigarettes to fully extinguishing campfires.

“We’re at a time now, coming out of social distancing, where Canadians can make a difference,” he said.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.