A complaint over the RCMP’s role in the arrest in the United States of a Toronto-area ISIS recruit has been referred to Canada’s new national security review agency, handing its members a challenging case early in their mandate.

A copy of the complaint obtained by Global News alleges Abdulrahman El Bahnasawy was “entrapped” by the FBI with the help of the RCMP, which was aware of his history of mental illness and addiction.

“Both agencies knew of his mental health problem and so entrapped him online, taking advantage of his unstable mental health, while he was manic and on the waiting list for mental health treatment,” the complaint alleges.

The case has been referred to the government’s National Security and Intelligence Review Agency, formed six months ago to increase the transparency of Canada’s national security activities.

El Bahnasawy is now serving a 40-year prison sentence in the U.S. after pleading guilty to plotting ISIS attacks in New York City. He is appealing the sentence.

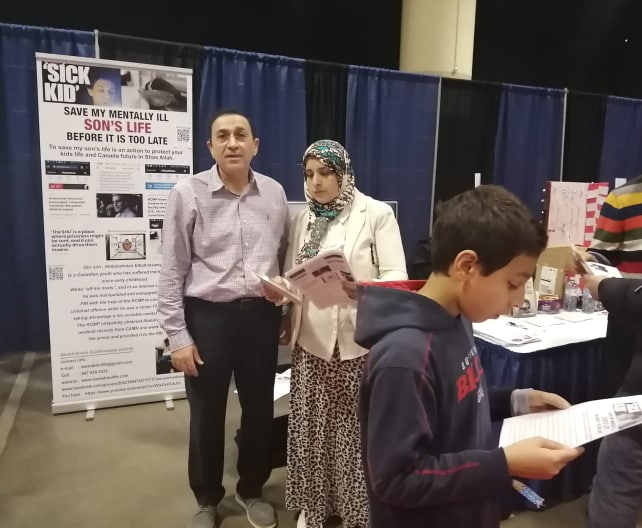

His parents said their son was 18, off his medication and “rarely left his room” in surburban Toronto when he was arrested in New Jersey in 2016 during a family road trip.

They have questioned why the RCMP, which knew about his mental health problems, cooperated with the FBI undercover investigation instead of helping their son get treatment.

“We hope our complaint is taken seriously and our government intervenes to bring our victim sick son back before it is too late,” his parents said in a statement.

An official at the review agency, known as NSIRA, wrote to the parents on Nov. 6, saying their complaint was being examined to ensure it was “not trivial, frivolous or vexatious or made in bad faith.”

NSIRA did not initially respond to questions from Global News. In a statement Tuesday, a spokesperson said she could not discuss complaints because they were private.

Get breaking National news

“Generally speaking, when NSIRA determines it will investigate a complaint, we begin the investigation by conducting a quasi-judicial process and hearings,” Tahera Mufti said.

Experts said there was no reason to decline the case, which touches on sensitive topics such as international cooperation and terrorism investigations in which mental illness is a factor.

“Sending the case to be reviewed by NSIRA was absolutely the right move,” said Prof. Stephanie Carvin, a national security expert at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs.

“NSIRA has the authority and mandate to look at operational information to review the files across government agencies.”

She did not take issue with the RCMP’s decision to investigate El Bahnasawy, since mental illness “does not preclude someone from engaging in violent extremism.”

But while the RCMP did not encourage El Banhasaway to travel to the United States, it also did not stop him. “NSIRA will have to decide if this was the correct policy to follow in its review,” she said.

The investigation began when the FBI infiltrated a group of co-conspirators in Syria, Canada, Pakistan and the Philippines.

In online messages, they planned attacks to be carried out in New York for ISIS. El Bahnasawy not only participated but also purchased bomb-making materials in Canada and shipped them to the U.S.

During the investigation, the RCMP obtained El Bahnasawy’s medical records from the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto and passed them to the FBI, which arrested him when he crossed the border a week later.

U.S. prosecutors alleged he had been plotting what he had called “the next 9/11.”

“He planned to detonate bombs in Times Square and the New York City subway system, and to shoot civilians at concert venues,” said Geoffrey S. Berman, U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York.

But his parents deny El Bahnasawy is a terrorist, describing him as “vulnerable, weak, isolated” and awaiting an appointment with a specialist in Ontario when he was taken into custody.

He is currently being held at a medium-security prison in Atlanta, but the parents said he needed to be “in a hospital and not in a prison” and want him brought back to Canada, where they argue he will have better access to treatment and medication.

The Canadian embassy in Washington, D.C., has been monitoring the case, emails released by the family show.

Questions over whether police should intervene to de-radicalize terrorism suspects were raised in the case of John Nuttall and Amanda Korody, who plotted to bomb the B.C. legislature on Canada Day in 2013.

They were convicted by a jury but later acquitted by a judge who said they had been entrapped by police, who continued an undercover investigation rather than examining a possible “exit strategy.”

“The RCMP has in place policies regarding vulnerability assessments in all undercover operations. So that was likely taken into consideration here,” Prof. Carvin said of El Bahnsawy’s case.

“In addition, recent court cases, such as the Nuttall/Korody entrapment decision are also having an impact on how the RCMP manages these kinds of cases with vulnerable individuals.”

The newly-created NSIRA reviews the activities of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service and Communications Security Establishment, as well as the national security and intelligence activities of all other federal departments.

It also investigates complaints, replacing and expanding on the role previously filled by the Security Intelligence Review Committee. Complaints against the RCMP that involve national security are part of its mandate.

Leah West, who teaches national security law at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs, said she could not see why NSIRA wouldn’t investigate.

The review would likely look at RCMP information sharing practices and whether procedures were properly followed, said West, a former Department of Justice national security lawyer.

“It’s not a swift process,” she said.

Stewart.Bell@globalnews.ca

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.