At just 46 years old, Karen Ward is almost considered a senior citizen in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

The drug policy advocate is also a drug user, one of hundreds who have made their home in the community where she’s lived for over a decade.

“If you haven’t seen somebody for a couple of weeks and then you run into them on a corner or in the alley, people are surprised: ‘I thought you were dead!'” she said.

The Downtown Eastside remains the epicentre of B.C.’s overdose epidemic. Vancouver Coastal Health says the area saw more than 100 deaths by residence per 100,000 population between 2017 and 2018.

Those premature deaths have created a nearly 15-year discrepancy between the average life expectancy for men in the DTES and men living in Vancouver’s West Side, states a July report from chief medical health officer Dr. Patricia Daly.

Data from the BC Coroners Service shows that between 2016 and June 2019, B.C. had 4,559 deaths. Just over a quarter of them were in Vancouver.

While the number of deaths has begun to trend down in recent months year over year, the data shows fentanyl and carfentanyl contributed to a majority of those deaths. In the case of carfentanyl, those instances are rising.

Ward says the solutions should be simple: provide a safe drug supply, decriminalize hard drugs and end the stigma surrounding drug use, the last of which pushes people to use alone without anyone to help them if they overdose.

But Canada’s political leaders have not yet committed to those moves.

“We need to recognize that this is happening,” Ward said. “Over 4,000 Canadians died last year over policies that our federal leaders can change. It’s an irrational massacre, and we can stop it.”

Get weekly health news

Where do the leaders stand?

The overdose crisis — largely driven by opioids — is not just a B.C. issue.

Between the start of January 2016 and the end of March 2019, more than 12,800 people in Canada died of apparent opioid causes, according to Health Canada.

On Sept. 27, Liberal Party Leader Justin Trudeau called the opioid crisis a “national public emergency.” But the parties vary in some key areas on how to address it if elected.

The Liberal strategy focuses on treatment, harm reduction, safe consumption sites, and new money for the provinces and territories to expand local programs. Leader Justin Trudeau has said his party will not consider decriminalization.

The Conservatives have not released their addictions strategy, but have signalled a more law and order approach to the addiction crisis while criticizing the Liberals’ plans for safe consumption sites.

The NDP plan includes declaring a “public health emergency,” decriminalizing drugs so people can seek treatment without fear of arrest, and better funding provincial programs.

The Greens plan to decriminalize possession and boost funding for treatment.

None of the parties have voiced support for creating a safe drug supply, though, which Ward says is critical to ending the crisis.

“We have to deal with it before it gets worse,” she said. “This is a poisoning in the very heart of the system that we’ve created.

“It indicts us all. Let’s be serious and address it, and we have to do it now.”

Doctor-created solution

One Vancouver doctor isn’t waiting for federal policy to create a safe drug supply. He plans to do it himself — through a vending machine.

Dr. Mark Tyndall has a prototype of the machine that dispenses a pre-programmed number of hydromorphone pills that are a substitute for heroin. The machine is set to be unveiled in the Downtown Eastside in a matter of weeks.

“The idea of offering people a safe regulated supply of drugs I think is what we do with any other poisoning epidemic, and this should be our approach with public health,” Tyndall said.

The eight-milligram pills cost about 35 cents each, and focus groups with drug users have suggested most people would need about 10 to 16 pills a day, according to Tyndall, who is also a professor of medicine at the School of Population and Public Health at the University of British Columbia.

He said the device includes a touchscreen and a biometric hand scanner on the side and pills would be dispensed in about 20 seconds for patients who have been approved to receive them, possibly several times a day.

“It’s a total misunderstanding of what’s going on if politicians continue to focus on recovery,” he said. “That’s a long march for a lot of people, and we have to start somewhere and meet them where they’re at.”

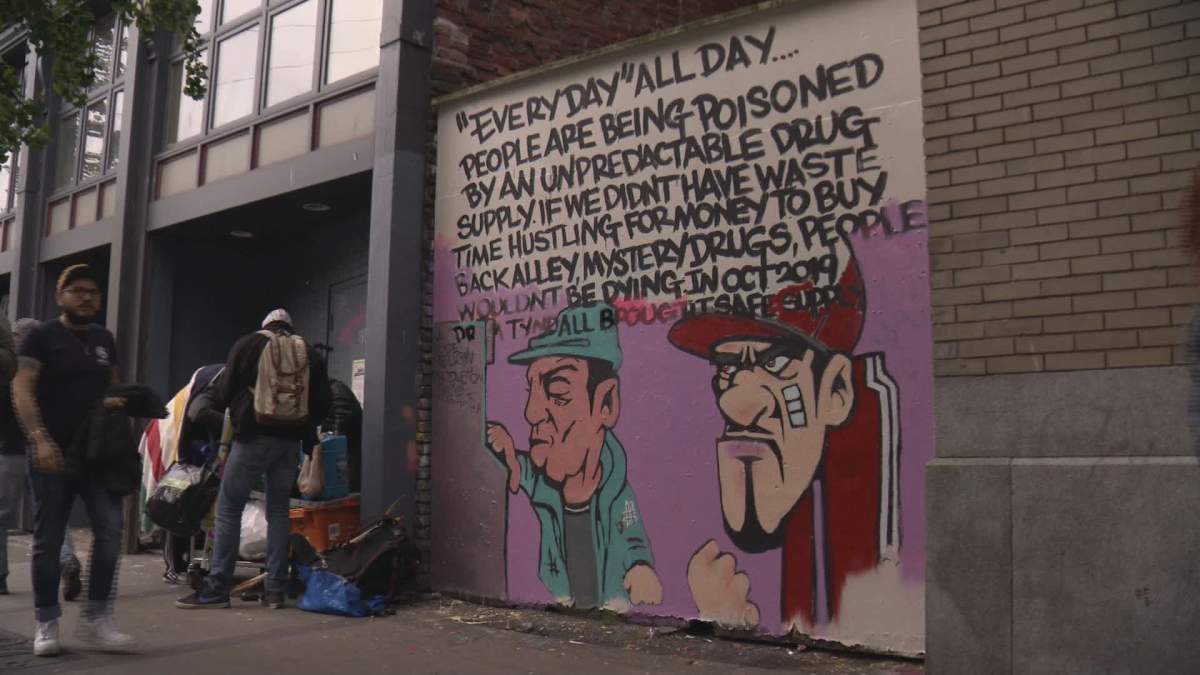

The idea has already caught on within the community. A mural recently painted on one DTES wall depicts drug users lining up to use the vending machine.

Ward says the idea is a great first step, not only to clean up the drug supply but also help end the stigma that sends so many people to their deaths.

“The machine isn’t going to look down on them,” she said. “The machine isn’t going to judge them.”

“The point of harm reduction is to meet them where they’re at. And they’re out there,” Ward added, motioning to the Downtown Eastside surrounding her.

— With files from Jordan Armstrong and the Canadian Press

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.