There have been plenty of 50th-anniversary commemorations this summer. The Apollo 11 moon landing. The Manson Family murders. The Stonewall Riots that gave birth to the gay liberation movement.

If we turn to music history, it was 50 years ago that The Who released Tommy. We heard of the mysterious drowning death of Rolling Stones founder Brian Jones. And, of course, Woodstock.

One thing missing from this list is the Toronto festival that played a larger part in bringing The Beatles to the end: The Toronto Rock&Roll Revival, an event that happened 50 years ago on Sept. 13.

READ MORE: Barefoot man arrested after breaking into Taylor Swift’s house

Promoters John Brower and Kenny Walker, fresh off producing a two-day event at Varsity Stadium at the University of Toronto that June, were intrigued by an event held a few weeks earlier in Detroit. Billed as the First Annual Rock&Roll Revival, the gig features local heroes The Stooges and The MC5 along with Chuck Berry, The Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band and Dr. John. Could they pull off something similar in Toronto?

They set about planning the Toronto Rock&Roll Revival, focusing on booking acts from the early days of rock’n’roll. Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, Boo Didley, Screaming Lord Sutch, and Gene Vincent were contracted to perform. A new group called The Alice Cooper Band signed on for double duty. Not only would they get their own set, but they would act as the back-up band for Vincent. The Chicago Transit Authority (later just plain Chicago), brought some jazz-rock fusion to the bill. The Doors were brought in as headliners at great expense.

- Posters promoting ‘Steal From Loblaws Day’ are circulating. How did we get here?

- Video shows Ontario police sharing Trudeau’s location with protester, investigation launched

- Canadian food banks are on the brink: ‘This is not a sustainable situation’

- Solar eclipse eye damage: More than 160 cases reported in Ontario, Quebec

A stellar lineup in retrospect, but at the time no one cared. Advance ticket sales were awful. When backers George and Thor Eaton (yes, of the department store) pulled their support, Bower and Walker, now deep in hock and facing total financial obliteration, came close to cancelling the show.

Weirdo producer Kim Fowley, who had been hired to be the official MC of the event, had an idea. Why not call up John Lennon and see if he’d want to drop by? After all, the lineup was packed with his musical heroes. What did anyone have to lose?

Brower finally got through to Apple at 6:30 a.m. Toronto time on Friday the 12th, 11:30 London time. He told the receptionist that he needed to speak to John about MCing a show the next day that was going to feature rock’n’roll royalty. Lennon was on the line in a flash. “Really? You have all these acts?”

“Yes,” Brower said. “I can’t pay you but I can get your first-class plane tickets.” (The Eaton brothers were back in the game by this time and fronted the money for the airfare.)

READ MORE: Suspected drug dealer arrested in connection with death of Mac Miller

Lennon was intrigued but returned a curveball. “Yeah, I’ll come, but I want to play.” Odd, considering that Lennon was deep into his heroin phase and leaving London meant that he’d be separated from his supply. But Brower quickly agreed to let Lennon do whatever he wanted and immediately arranged plane tickets for Lennon and Yoko Ono.

“What about your band?” asked Brower. Lennon didn’t have one. He was, after all, a member of The Beatles. He’d been in the studio with them working on the Abbey Road album as recently as Aug. 20. His first two solo albums were studio affairs made without a permanent back-up group. Lennon got on the phone to find someone, anyone, who’d be willing to fly to Toronto with him the next day. He ended up with Eric Clapton, future Yes drummer Alan White, and bass player Klaus Voorman, an old friend from The Beatles’ days in Hamburg and the designer of the artwork for the Revolver album.

Back in Toronto, when Brower tried to tell everyone that he’d bagged a solo performance by a Beatle — Lennon’s first proper public performance since The Beatles’ last show at Candlestick Park in August 1966 — no one believed him. Word on the street was that he was lying and just trying to scam people into buying tickets. Local radio refused to cover the story. The Vagabonds Motorcycle Club, which Brower had hired to escort Lennon from the airport to the gig, was threatening terrible things if they rode out there to find no Beatle.

Lennon had, in fact, had second thoughts. He told his people to send his regards and some flowers, saying that he and Yoko couldn’t make it. That’s when Clapton started screaming at Lennon that he’d made a promise and he had to go through with it. Lennon eventually folded.

READ MORE: 911 audio from Kevin Hart car crash released: ‘He’s not coherent at all’

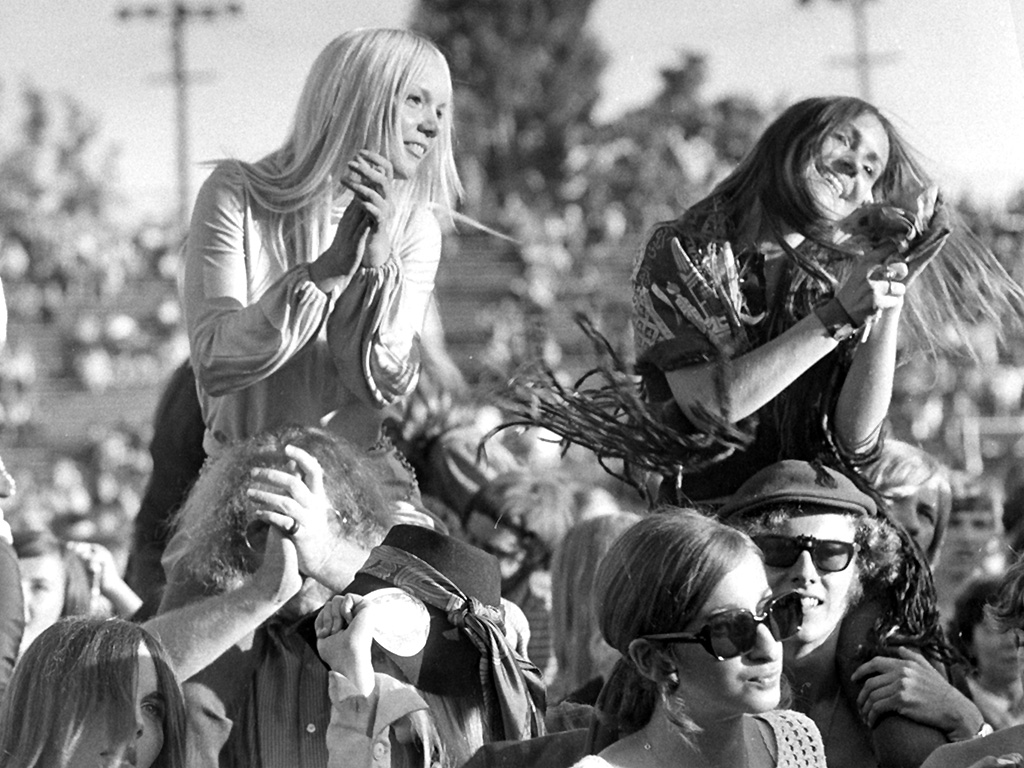

Ticket sales remained flat until the afternoon of the 13th after the 14-hour show had already begun when the wire services reported that Lennon had indeed boarded an aircraft headed for Toronto. Radio stations from Ottawa to Toronto to Detroit went wall-to-wall with the news. People ran to Varsity Stadium and by nightfall, all 20,000 tickets had been snapped up.

Meanwhile, on the plane from Heathrow, Lennon started to panic. What if he’d lost the ability to play live? What if the decidedly experimental music of The Plastic Ono Band turned the crowd against him? To bomb in front of his musical heroes would be unbearable. He hadn’t slept at all the Friday night and Clapton spent most of the flight reassuring John that things would turn out okay. Besides, it was too late to back out now. They were more than halfway across the Atlantic. They passed the time by holding their only rehearsal in the back of the Boeing 707.

Lennon started to feel a little bit better when his group was met by The Vagabonds. The limos received an escort from the airport — 40 bikes up front, 40 in the back — straight to the backstage area at Varsity on Bloor Street. When Lennon ran into Berry, Lewis, Vincent, and the others in the crappy dressing rooms, he reportedly fell to his knees in an “I am not worthy” greeting. Maybe things would be all right.

Then Lennon took a look at the audience. All those people there to see him. Not The Beatles, but John Lennon on his own. This led to another round of drug-addled paranoia. Lennon was terrified to go on. Plus without his smack fix, he was going through cold turkey withdrawal and had been throwing up for hours. A little coke from a local dealer helped sort things out.

Fowley came to the rescue again. Stepping on stage, he asked the crowd to create a special vibe for Lennon by holding up lighters and lit matches to create the appearance of thousands of calming candles burning in the night.

“Everyone get out your matches and lighters, please. In a minute I’m going to bring out John Lennon and Eric Clapton and when I do I want you to light them and give them a huge Toronto welcome.” It worked.

Beatles fixer Mal Evans is quoted in The Beatles Bible: “He did a really great thing. He had all the lights in the stadium turned right down and then asked everyone to strike a match. It was a really unbelievable sight when thousands of little flickering lights suddenly shone all over the huge arena.”

Thus was born the rock’n’roll tradition of holding up lighters at a concert.

Lennon, Yoko, and the band finally appeared, launching into a rendition of Blue Suede Shoes. That was followed by songs like Dizzy Miss Lizzy, The Beatles’ Yer Blues and a brand new song called Cold Turkey.

Yoko got her chance to do her thing, but her caterwauling — which included a 17-minute shriek entitled Don’t Worry Kyoko (Mummy’s only looking for her hand in the snow) / John, John (Let’s hope for peace) — didn’t go over very well. Perhaps it was best that she did all her vocalizing from inside a large bag.

Things went better than the could have possibly dreamed. Afterward, he reportedly told Brower, “I haven’t felt so alive in years.” Later Lennon said, “The buzz was incredible. I never felt so good in my life. Everybody was with us and leaping up and down doing the peace sign because they knew most of the numbers anyway, and we did a number called Cold Turkey we’d never done before and they dug it like mad.”

Returning to London with new energy and purpose, Lennon realized that maybe he didn’t need The Beatles after all. Things had grown increasingly hostile between the four of them over the last year. Who needed that kind of aggravation? Hadn’t he just proven that there was life beyond the Fab Four?

There were a few things left to clear up with the Beatles, including some final sessions for what would be the Let It Be album. Ringo recalls a meeting at Apple Corps HQ in the weeks after the Toronto show. In the Beatles Anthology, he recounted: “After the Plastic Ono Band’s debut in Toronto we had a meeting in Savile Row where John finally brought it to its head. He said, ‘Well, that’s it, lads. Let’s end it.’ And we all said ‘Yes.’”

An impulsive decision to fly to Toronto led to the break-up of the most important band in rock history. That’s worth remembering not just 50 years later, but for all time.

—

Alan Cross is a broadcaster with 102.1 the Edge and Q107, and a commentator for Global News.

Subscribe to Alan’s Ongoing History of New Music Podcast now on Apple Podcast or Google Play

Comments