Canada has been at the forefront of nuclear energy for almost 80 years. Canadian uranium and Canadian researchers were central to the U.S. development of nuclear weapons in the Second World War.

The first test reactor was built at Chalk River, Ont., giving this country a head start in developing nuclear energy for peaceful purposes after the war. Ottawa created a Crown corporation, Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd., and we soon emerged as a leading nuclear nation, building Candu reactors for electricity in this country, and selling Candu technology to several countries around the world.

The province of Ontario became one of the most nuclearized jurisdictions in the world. Three major nuclear plants were built at Pickering and Darlington on Lake Ontario, and the biggest one in Bruce County on Lake Huron. Today, nuclear power accounts for 60 per cent of the electricity in the province.

From day one, there has been a current of opposition to nuclear power, and like an electrical surge, criticism has spiked at times – during cost overruns in the province, and in the aftermath of disasters abroad. The partial meltdown at Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station in Pennsylvania occurred just as a federal election campaign was getting underway in Canada in the spring of 1979.

READ MORE: SNC-Lavalin appoints U.S. nuclear exec to head Candu Energy

Then-leader of the New Democratic Party Ed Broadbent called for a moratorium on expanding nuclear power in Canada. The opposition leader, Joe Clark, said he would have a committee of Parliament look into all aspects of nuclear power.

The immediate danger from Three Mile Island would pass and so did the political debate. Much the same happened after Chernobyl in 1986 and Fukushima, Japan in 2011. The disasters were horrific and chilling, but the loud debate over nuclear energy eventually receded.

Decades into the nuclear era the world has suffered periodic nuclear catastrophes, but it has also been left with a legacy of relatively safe use of nuclear energy.

READ MORE: BWXT Nuclear Energy Canada lands $168M contract extension with OPG

In fact, the fear that may have existed near nuclear plants when they were first built, has largely been replaced by confidence in the safety of nuclear technology.

“It’s been here for 50 years, and it’s a part of life,” the mayor of Kincardine, Ont., Anne Eadie, told Global News.

Kincardine sits next to the Bruce Power facility. About one-third of the plant’s 4,200 workers live in Kincardine.

“We are quite, quite comfortable. I would think there is more risk going on our roads to work than actually working at a nuclear power plant,” said Eadie.

While the nuclear creating heat and electricity has been well contained in reactors, ceramic pellets and fuel bundles, we have been left with big a problem that everyone saw coming: the hazard posed by nuclear waste.

At the Bruce plant, low and intermediate level wastes are accumulating. Low-level includes worker clothing and tools. Typically, they could be radioactive for 100 years. Intermediate-level waste is described as resins, filters and used reactor components that could be a hazard for 100,000 years.

READ MORE: Ontario NDP only party speaking out against nuclear waste bunker near Lake Huron

Ontario Power Generation has slowly made headway for a plan to bury this waste in a deep underground repository next to the Bruce plant. Much of it now sits in large tanks with row upon row of cement lids poking above the surface.of the ground.

Fred Kuntz, wearing an OPG hard hat, gazed over the containers: “This is all safe storage for now, but it’s not really the solution for thousands of years. The lasting solution is disposal in a deep geologic repository.”

He pointed to a stand of trees. “The DGR would be built here.”

Some think that’s a terrible idea. The repository could leak, it could be attacked, and the location on the Bruce site is barely a kilometer from Lake Huron, which has opponents on both sides of the Great Lakes up in arms.

READ MORE: Saskatchewan giving early consideration for small nuclear reactors

“There isn’t a magic bullet. It’s not like we can put it out of sight and we’ve solved the problem.” said Theresa McClenaghan of the Canadian Environamental Law Association.

She suggests humans have little concept of how long 100,000 years is. She questions whether the facility would last and whether we can be sure we’ll be able to communicate the dangers to some future civilization.

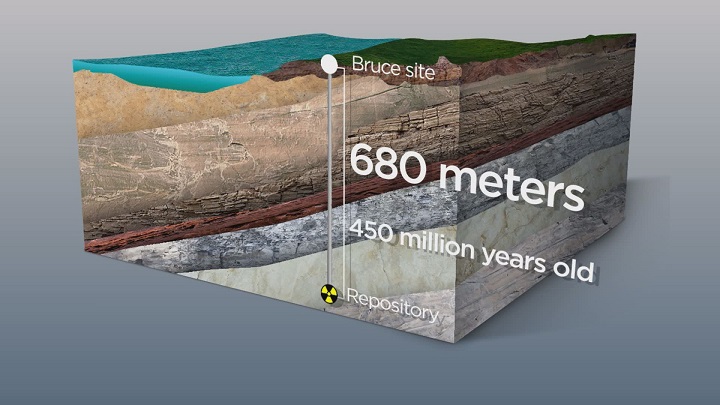

OPG says the proximity to Lake Huron is much more distant when you plunge the waste into rock more than half a kilometer below the surface. That’s more than three times deeper than the depth of the lake in sedimentary rock that is 450 million years old.

Fred Kuntz of OPG said, “The rock at 680 metres deep is impermeable. It’s dry. It’s strong. The geology at that depth below the site has been isolated from any groundwater or the lake for hundreds of millions of years.”

The deep geological repository was approved by an environmental review panel in 2015, but both the Harper and Trudeau governments have put off giving the final go ahead. It now appears to hinge on the approval by indigenous people in the region.

READ MORE: Tiny power plants hold promise for nuclear energy

Get daily National news

For the Saugeen Ojibway Nation, it’s about time they were consulted. Fifty years ago, the concerns of indigenous people were an afterthought when it came to major public policy decisions.

The nuclear plant was built on the traditional land of the Saugeen Ojibway. OPG says it has come to recognize the “historic wrongs of the past” and is negotiating compensation for those wrongs. And moving forward, OPG has given its assurance that the repository will only be built if the Saugeen Ojibway approve – from an afterthought to the power of veto over a multibillion-dollar enterprise.

“It’s here,” he said. “We didn’t ask for it. It’s not a problem of our own creation. Certainly had we been part of the conversation from the outset, things probably would have been a lot different.”

There is a kind of irony for the Saugeen Ojibway in dealing with nuclear waste. Among Canadians, First Nations have always emphasized the need to care for the land and the water. They have taken the long view of their responsibility to future generations, but here they are confronted with something beyond even their historic comprehension of obligation.

READ MORE: Sask., Whitecap Dakota First Nation sign environmental regulation agreement

Kahgee says the elders have traditionally looked seven generations ahead. Nuclear waste requires wisdom that extends a thousand generations.

Kahgee says it is a heavy decision and in some ways unfair.

“Our people don’t see it as a simple project. We see that as a forever project, because that’s how long it will be here. And if it’s allowed to proceed, it will forever become part of the cosmology of our people, so how can we not be part of that conversation?”

Kahgee says it is empowering, but also “very scary when you consider the gravity of what you’re dealing with.”

Bottom line, nuclear waste exists, and it exists on their land.

“We think about stewardship,” Kahgee told Global News.

“Implicit in stewardship is the responsibility to act. I hope we’re prepared for the next conversation, which is, ‘What are we going to do about the problem?’ because it’s not going away.”

Remarkably, this is the relatively easy stuff to deal with: low- and intermediate-level nuclear waste. An even bigger problem is high-level radioactive used fuel. It too is piling up, primarily at the three big Ontario plants. It may be toxic for a million years.

READ MORE: Meadow Lake Tribal Council clean energy project to power thousands of homes

Now what’s to be done? Enter the Nuclear Waste Management Organization. It was established in 2002 under Ottawa’s Nuclear Fuel Waste Act by Canada’s nuclear electricity producers in Ontario, Quebec and New Brunswick.

The NWMO is tasked with coming up with a long overdue plan for Canada’s used nuclear fuel. In 2005 the NWMO recommended and in 2007 Ottawa accepted a proposal to contain all of the country’s used fuel in one deep geological repository.

If you’re keeping count, that would be a second DGR in Ontario. The estimated cost of this project is $23 billion. One NWMO executive described it as the biggest infrastructure project you’ve never heard of.

READ MORE: Atlantic Canada clean energy collaboration receives $2M federal investment

The organization wants the public to learn more about it. It seems that the first response to nuclear waste is public resistance, so the more they can talk about it, the better the chance of persuading Canadians of its merits.

Ultimately they need to find one particular community to be a “willing host” for what amounts to 57,000 tonnes of used nuclear fuel.

To put that in Canadian jargon, the NWMO says the roughly three million used fuel bundles would fit into eight hockey rinks up to the top of the boards. Doubtless, most communities would take the hockey rinks over the bundles.

NWMO does not lack for communities willing to consider taking the waste; more than 20 expressed interest. That number has been trimmed to five potential sites: Ignace, Manitouwadge, and Hornepayne in northern Ontario, and Huron-Kinloss and South Bruce in southwestern Ontario.

The NWMO pitch paints a picture of a repository that will be safe, essentially forever. The construction and transportation will ensure one small community decades of economic growth.

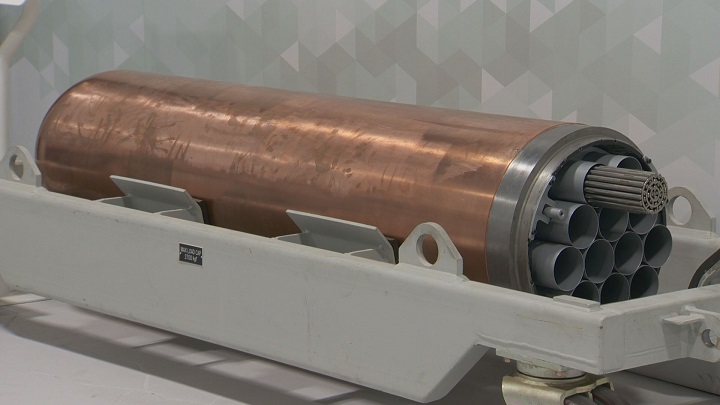

The waste management organization is convinced it has the engineering figured out. The small ceramic nuclear pellets that fit into tubes are collected into those familiar nuclear bundles – each about the size of a fire log and a lot hotter in terms of radiation.

The plan is to pack the bundles into carbon steel tubes coated in copper – 48 bundles per container. They look like a big torpedoes. Each one will be packed snugly into what look like coffins made of a special clay called bentonite.

Thousands of bentonite boxes will be moved by robotic machines into hundreds of long placement rooms deep underground. Dried slightly, the clay will expand and plug every last space, ultimately sealing the repository. Multiple barriers to contain the waste in rock so old that it would take millions of years for water or radioactivity to make its way out – that, in a nutshell, is the science.

One of NWMO’s technical experts, Erik Kremer, says it will work in either the Canadian Shield north of Lake Superior, which is billion-year-old granite, or the 300-million-year-old sedimentary limestone in western Ontario.

Either way, he said the rock has been stable for much longer than the time needed for the radioactivity to subside.

“I mean if it’s billion-year-old rock, it’s not much to ask for another million years,” Kremer said.

And, he added, the containers are designed to withstand the crushing weight that could come from a future earthquake or even glaciers in the next ice age.

“This needs to be able to withstand those forces,” he said.

WATCH: Proposed ‘ideal’ site for nuclear waste storage in Ontario raises concerns

If you think environmentalists are skeptical of the low and medium waste repository, just listen to their take on burying this stuff.

“I mean, it sounds crazy to be talking about that. We’re talking about waste that’s going to be toxic for hundreds of thousands of years.” said the Canadian Environmental Law Association’s Theresa McClenaghan.

Rather than lock in a decision now, she suggests fortifying the temporary storage for a few more decades and waiting for new and better technologies to come along.

Coincidentally, Gerard Mourou, the Nobel-Prize-winning physicist is turning his expertise in lasers toward zapping the radioactivity out of nuclear waste.

Maybe it’s far-fetched and years away, but McClenaghan said there are no good solutions on the table right now, so “let’s choose the least bad alternative.”

Brennain Lloyd with a nuclear watchdog group, Northwatch, agrees, suggesting a deep repository will leave future generations few options for new ideas.

“What we should not do is foreclose on future generations’ opportunity to do better,” she told Global News.

The NWMO says it’s time to act. Ben Belfadhel, the organization’s vice-president in charge of site selection, says there’s no guarantee that there will be a better solution 200 or 300 years from now.

“Doing nothing is not an option,” he said.

“The waste is there, and we have to do something to protect future generations. We are the generation that is benefitting from nuclear, and we owe it to future generations to provide them with the solution for the long term management of nuclear fuel,” said Belfadhel.

He says the plan also leaves scope for technologies to change, so there will be opportunities for their plans and this project to adapt.

Still, he is seized by the enormity of the decisions his organization must make.

“When you look at what we are doing and protecting future generations, I think for me it’s a noble project,” said Belfadhel.

READ MORE: Ontario PCs introduce legislation to scrap Green Energy Act

It still comes down to finding a willing host. The NWMO wants to pick the site by 2023. The five communities on the NWMO’s short list are all relatively small and rural, sit above a suitable rock formation, and they have all demonstrated an openness to the project so far.

Each has a liaison committee working with the NWMO to hold regular meetings where residents can raise questions and learn more about the project, but what a decision for one small town to make.

Mildmay, Ont. is a small farming town in South Bruce. It’s not home to the Bruce Power plant, but it’s close enough that people here are familiar and comfortable with nuclear as a neighbor.

Jim Gowland is a local farmer and chaired the most recent liaison committee meeting.

“Certainly our community has seen the benefits of Bruce Power and the nuclear industry. We know the used fuel is sitting up there in interim storage, and there has to be a solution. And I think our community can be a part of evaluating that solution,” he said.

The NWMO sent a representative to that same meeting to reassure townsfolk on the issue of transporting nuclear fuel. Caitlin Burley brought a prop with her – a metal bolt that looks like a 10-pound barbell.

She explained that 32 such bolts are used just to keep the lid on one of the containers that would be used to transport the used fuel – 35-tonne containers, each carrying four tonnes of fuel.

She also played a video that showed containers being tested – a train in the UK ramming a nuclear container in a 1984 test, and a German test in 1999 in which a propane tank car exploded. The nuclear containers survived intact.

READ MORE: Exclusive: Shutting down Ontario nuclear plants, buying Quebec hydro is path to cheaper electricity

Most people watching seemed satisfied. One attendee, Ron Schnurr, said afterward, “The thing is we have to trust somebody, and we do hope these professional people know what they’re talking about.”

Dennis Eikeimer was not convinced: “It’s so tremendously dangerous the nuclear waste.”

He has a background in physics, and he’s not sold on long-term storage underground.

“And if it does leak, there is absolutely nothing they can do,” he said.

Instead he suggested to “just store it and do some more research.”

It’s hard to ignore the used fuel as it accumulates above ground. Bruce Power has more than 1.2 million nuclear bundles of used fuel. A little more than half of it is in wet storage – in big pools of water where the radioactivity can “cool down” for seven to 10 years.

The rest is older fuel, already moved into dry storage in massive concrete and steel containers on site. New containers are brought in regularly, tested, and then filled with 384 used fuel bundles.

The massive containers – 1,539 of them – are put in a giant hangar, warm enough to the touch that there is no need to heat the building.

Picking a host community, getting regulatory approval, building the repository, and transferring high-level waste will take the next 50 years.

It is separate from the OPG plan for low- and intermediate-level waste, which could have an answer from the Saugeen Ojibway Nation by the end of this year, and federal approval in 2020.

As it turns out, two of the NWMO sites for high-level waste – South Bruce and Huron-Kinloss – are also on Saugeen Ojibway land, so they may ultimately have to decide on separate nuclear waste projects on their land.

“When you think of the sacrifices our ancestors made, what they were trying to do is protect what was sacred to them . . . that relationship to the lands and waters. It’s a responsibility we have to those generations yet to come. So that we take very seriously,” said Randall Kahgee.

A deep geological repository is a massive and expensive proposal and will take decades to build and safely secure Canada’s nuclear waste. There is clearly momentum towards constructing a repository. If so, it seems like one more question may arise in the years ahead: does it really makes sense to build two?

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.