A suicide bomber from Calgary strikes near Baghdad. A Windsor man masterminds the torture and killing of foreigners at a Dhaka bakery. Two London, Ont., gunmen take hostages at a gas plant in the Algerian desert.

Canadian terrorists have killed and injured more than 300 in other countries since 2012, according to figures compiled by Global News that document the victims of so-called extremist travellers.

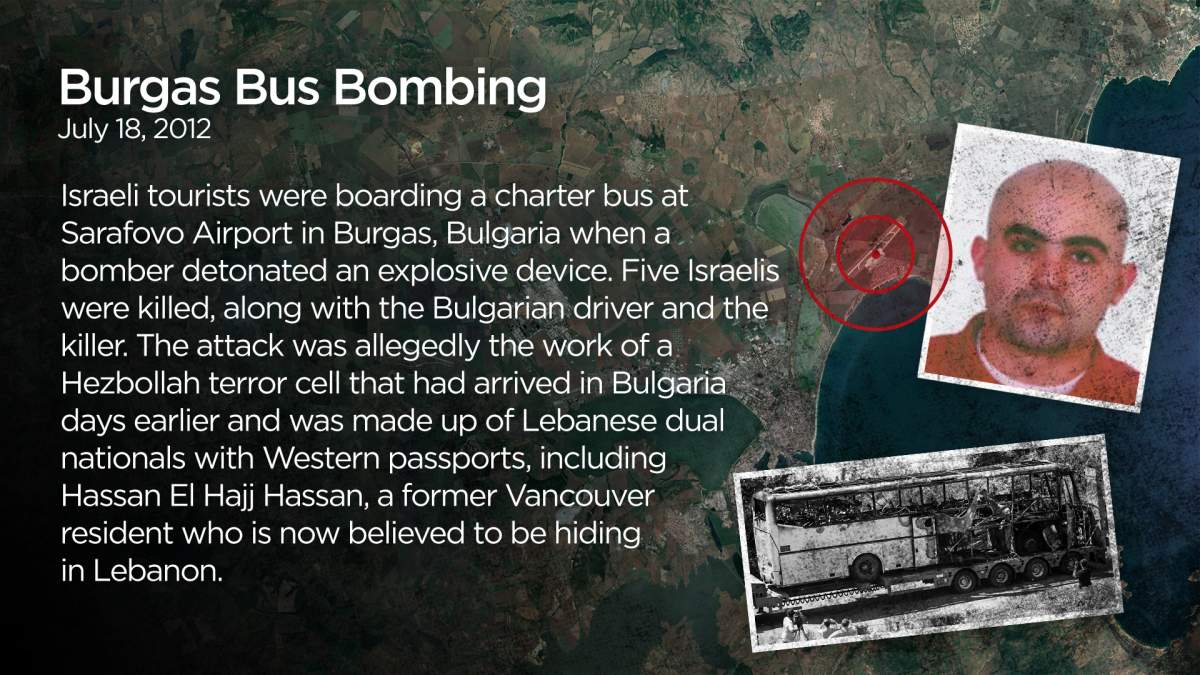

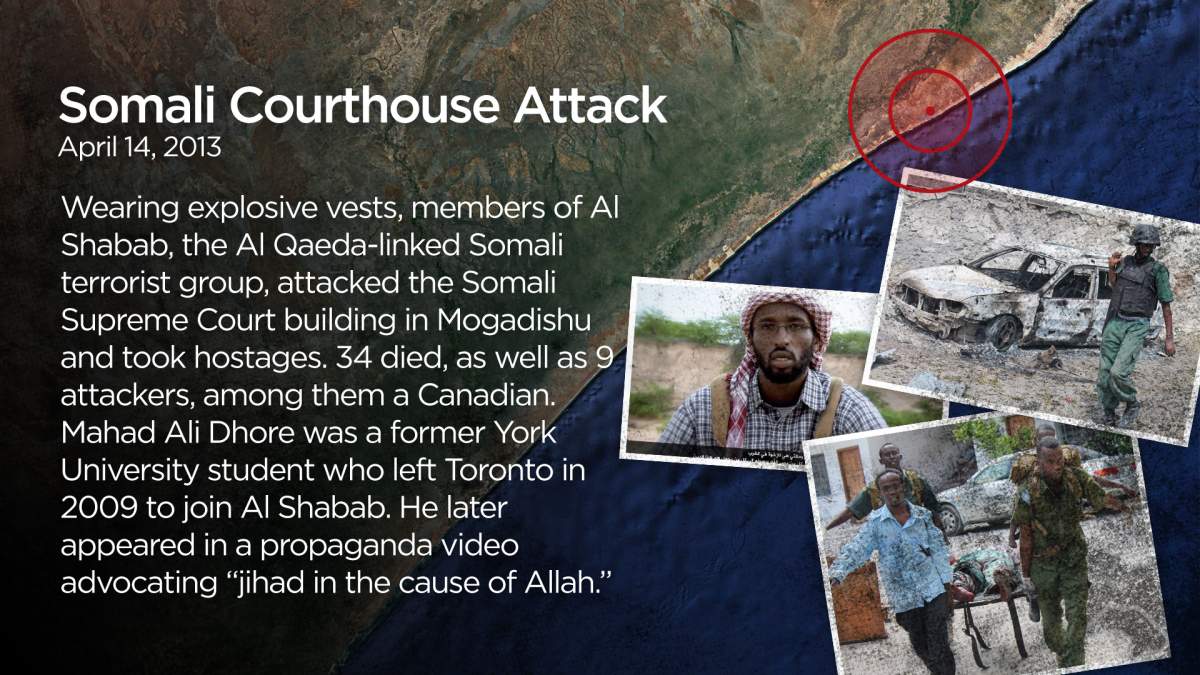

Fatal attacks in Algeria, Bangladesh, Bulgaria, Iraq, Russia, Somalia and Syria were attributed to Canadians during that time. An attack in Michigan resulted in no deaths but seriously injured a police officer.

Citizens of 19 countries were killed in attacks involving Canadian perpetrators, including locals and British, Colombian, French, Indian, Israeli, Italian, Filipino, Japanese, Malaysian, Norwegian, Romanian and U.S. nationals.

The figures are an attempt to tally overseas terrorism casualties attributed to Canadians from the time that numbers of extremist travellers began to spike in 2012 until the territorial defeat of ISIS last month.

Global News compiled the data from the Global Terrorism Database, Canadian Terrorism Incident Database, government documents, interviews, news reports and releases by terrorist groups. Included were attacks in which Canadians were direct participants or accomplices.

A total of 127 victims reportedly died in the attacks, and 195 were injured. Fifty-five attackers also died.

Four of the attacks killed more than a dozen victims and were worse than any mass murder in Canada since the 1985 Air Indian bombings by Sikh extremists. Injuries included stab wounds, burns and cuts caused by flying glass.

“While Canadians are right to think that terrorism generally happens less in our country, we also need to keep in mind that we export a lot of terrorism in different forms all over the world,” said Toronto-based terrorism researcher Prof. Amarnath Amarasingam.

Canadians have long been active in foreign terrorist groups, but their numbers increased sharply following the start of the Syrian conflict. In 2013 alone, overseas attacks in which Canadians played key roles killed 90 and wounded 98.

A February 2014 RCMP document noted the “growing” participation of Canadians in foreign conflicts and acts of terrorism and called preventing “high-risk individuals” from leaving the country a “challenging but important task.”

The government subsequently ramped up efforts against extremist travellers — placing them on the no-fly list, arresting them at airports, seizing their passports and having them intercepted as they transited through Turkey.

But some were still able to find their way to foreign terrorist groups.

“Unless there is some legitimate reason to prevent people from traveling to conflict zones, the rights of mobility contained in Section 6 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms apply,” the RCMP wrote in “Foreign Fighters: Preventing the Security Threat in Canada and Abroad.”

WATCH: Former CSIS analyst discusses the priorities of security agencies and preventing terrorists from leaving Canada

Former Canadian Security Intelligence Service analyst Phil Gurski said government agencies struggled at times to come up with solid evidence proving that someone preparing to travel intended to participate in terrorism.

“We may know that you’re completely radicalized and that you’re possibly open to the idea of taking part in an attack but we don’t necessarily know your intent,” said the former intelligence official.

Get daily National news

Another challenge is that those prevented from travelling may conduct attacks in Canada instead. In 2014, such attacks left two dead, and in 2016, a suicide bomber was killed and his cab driver injured.

“So it’s almost like you’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t,” Gurski added.

Meanwhile, the foreign conflicts that have attracted Canadian extremists remain mostly unresolved, and Al Qaeda and ISIS affiliates continue to operate from West Africa to Southeast Asia.

As a result, governments need to be cautious about reducing their focus on Islamist extremism as they tackle the emerging threat of right-wing extremism, Gurski said.

Many of the Canadians who went abroad ended up as terrorist combatants whose killings were rarely publicized and were therefore difficult to track.

A few held senior positions and were likely responsible for deaths — notably Fawzi Ayoub, a former Toronto convenience store worker who was a Hezbollah commander in Syria, and Abu Bakr Kanadi, who led an English-speaking ISIS faction known as the Anwar al-Awlaki Brigade.

Following his capture in Syria in January, Mohammed Khalifa of Toronto admitted to fighting with ISIS and narrating propaganda videos that showed the mass executions of at least 10 prisoners.

Another Canadian, who went by Abu Huzayfah, returned to Toronto and told a reporter he had executed two prisoners while serving in the ISIS religious police in Manbij, Syria.

But Global News could not verify the alleged killings mentioned above and did not include them in its calculations.

While the casualty figures suggest Canadian terrorists are responsible for significant bloodshed in other countries, experts said that was often overlooked in public debate about national security.

“Our guys and girls have caused a lot of harm abroad, and this is something we never really factor into our analysis of Canadian terrorism, at least in terms of public awareness of the issue,” said Amarasingam, senior research fellow at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue.

The grief Canadians have caused abroad “should also make us think twice about arguing against the repatriation of captured foreign fighters,” he said.

The deadliest attack since 2012 was by a faction that included Xristos Katsiroubas and Ali Medlej, high school friends from London, Ont., who “were introduced to a radical form of Sunni Islam through associates,” according to the transcript of a British coroner’s inquest.

After leaving Canada in 2011, they joined up with Algerian terrorist leader Mokhtar Belmokhtar, formerly a leading figure in Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb who formed his own splinter group and, in December 2012, announced his intention to target western interests.

The In Amenas gas plant was easy prey: jointly owned by BP and Statoil, it was an inadequately defended facility close to the Libyan border with 800 workers, many of them foreigners.

According to witnesses, Katsiroubas was a “clear leader” of the terrorists who stormed the plant early on Jan. 16, 2013. He identified the foreign nationals, held them captive with explosives and relayed the group’s demands for the release of prisoners held by the U.S. and Algeria.

Forty people from 10 countries lost their lives during the four-day siege, and 29 of the terrorists died when Algerian forces retook the compound. The RCMP later identified Katsiroubas and Medlej among the bodies.

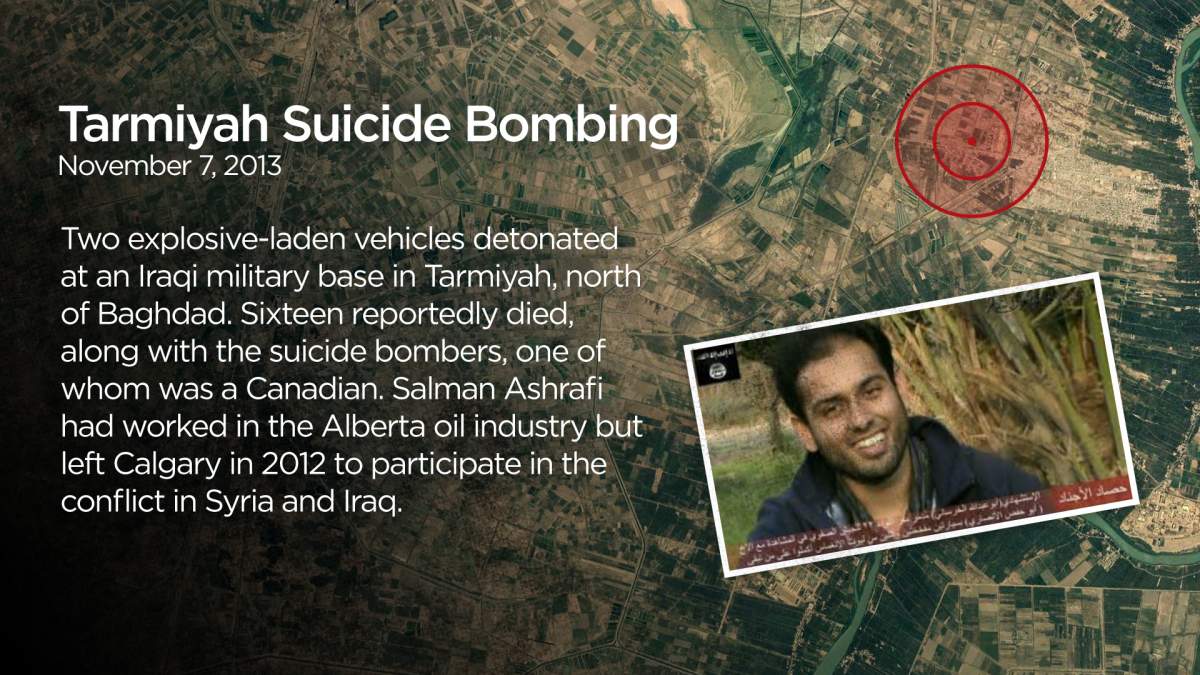

Ten months later, the worst known suicide bombing by a Canadian occurred when Salman Ashrafi, a former Alberta oil industry analyst, and another attacker detonated explosive-filled vehicles in Tarmiyah, Iraq.

The target was the headquarters of the Iraqi Army’s 22nd Brigade. ISIS said 46 were killed. The Iraqi embassy in Ottawa said 12 died. Global News counted 16 dead in its calculation, which was the number reported by the Global Terrorism Database.

Iraqi Ambassador Abdul Kareem Kaab said Iraq had been the victim of scores of such attacks and a “large number” were carried out by foreign nationals.

“Many of those terrorists are individuals who are known to the security authorities in their homeland as dangerous fanatics,” said the Ottawa-based diplomat. “The duty of the governments of those countries is to prevent those terrorists from travelling.”

The most recent documented attack abroad was in Flint, Mich. After writing a letter to his wife saying he loved jihad more than he loved her, Amor Ftouhi left Montreal and tried unsuccessfully to buy an assault rifle at a U.S. gun show.

Armed instead with a knife, he entered Bishop International Airport on June 21, 2017 and stabbed an airport officer, Lt. Jeff Neville, in the neck. Once in custody, Ftouhi spoke about Syria and Iraq and called the United States a “bastard nation.” Neville survived.

“We shouldn’t be exporting our problem,” said Gurski, the author of the book Western Foreign Fighters. “The onus is on us to prevent it, whether it’s through passport seizure or peace bonds or charges.”

“If we’re aware of it we should stop it.”

Stewart.bell@globalnews.ca

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.