The economic downturn that gripped Alberta’s economy and job sector starting in October 2014 took a toll on nearly every working individual in the province — no matter their age, gender or the industry in which they worked.

In the years since the end of the recession, in October 2016, the province has slowly rebuilt its workforce, but it’s been an uphill battle for thousands of people and the bounce-back varies greatly across the province.

Three major differences have emerged since the end of the recession, according to University of Calgary economist Trevor Tombe: gender, age and where people live are playing into how Albertans are rebounding.

Employment by gender

Men and women across Alberta experienced the recession differently when it hit nearly five years ago, Tombe said, and men lost jobs at a higher rate than women.

“If we look at the employment rates across different groups of Alberta workers, we see the largest drop, by far, is among young men under the age of 25. Their employment rate now is 12 whole percentage points lower than it was before the recession started. That is an extremely large drop.”

According to Statistics Canada data, at the start of the downturn, 1,272,300 men were employed in Alberta. By the end of the recession in October 2016, that number had dropped to 1,239,200.

By February 2019 — the most recent statistics available — men’s employment had bounced back to 1,255,6000 — falling short of the pre-recession level.

Comparatively, 1,017,200 women were employed in October 2014, and that number actually rose over the duration of the recession to 1,037,100.

As of February 2019, 1,074,500 women were employed in Alberta.

“They have not only recovered the losses through the recession but have increased even more beyond what those losses were,” Tombe said. “That has drawn many more prime-age Alberta women into the labour market. So the participation rate — the fraction that either have a job or are currently looking for one — is higher than at any point in Alberta history.”

Why?

Get daily National news

Tombe said the difference boils down to the nature of jobs that were affected when the recession hit: oil and gas, construction and manufacturing — which are male-dominated sectors.

“In 2018, the entire increase in Alberta employment — which was about 21,000 — is accounted for by gains among women,” Tombe said. “There was little to no increase in employment among men as a whole that year.”

Most of those women found jobs in health care, Tombe said, as well as social services. And most of those positions were either in the private sector or created through self-employment.

Employment by age

The level of success in re-entering the job market also depends on age, especially when it comes to younger men, Tombe said.

According to Statistics Canada, Albertans between 15 and 24 years of age saw a dramatic drop during the recession — from 330,100 employed in October 2014 to 308,600 in October 2016.

Since then, it’s continued to drop, with only 282,800 people in that age bracket employed in February 2019.

Breaking that down by gender, young men saw the most dramatic drop in employment. At the start of the recession, 182,000 men aged 15-24 were working in Alberta and two years later, nearly 20,000 of them had lost their jobs. In February 2019, that number had dropped again to 143,000.

Tombe said many of those young men were lower-skilled, some of whom didn’t finish high school, but were earning large wages at jobs that were subject to heavy losses.

“The recession is going to disproportionately lower employment among men,” Tombe said.

“And the job losses in oil and gas, they were not really the jobs associated with oil production – we produce more barrels now than we did in 2014 – but the job losses were in support activities; exploration, drilling, site services – jobs where young men are also some of the first to be let go.”

Tombe added that nearly half of the people out of work are exploring retraining and educational opportunities, but at the same time, half have withdrawn from the workforce, potentially hurting future employment and serving another blow to the province’s economy.

Employment by region

The recession recovery also varies greatly based on where people are employed or looking for new jobs.

According to Tombe, there are three areas of the province that show a clear difference between growth, contraction and stagnation in the job market.

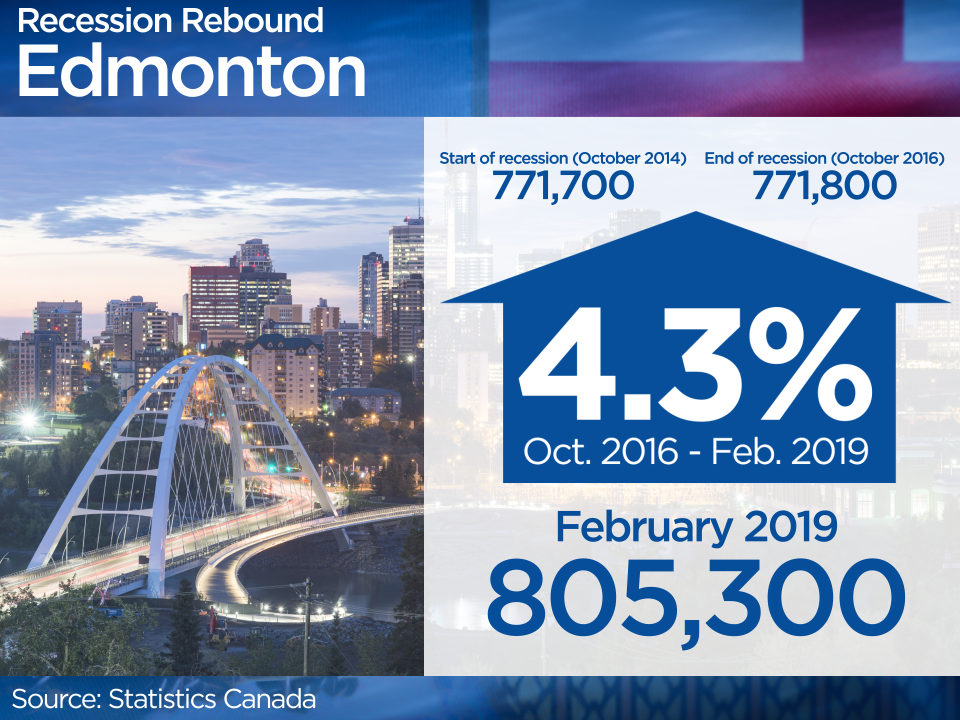

Edmonton and northwestern Alberta have seen a stronger recovery than the rest of the province. Edmonton saw 771,700 people employed in October 2014, which actually rose by 100 jobs by October 2016, according to Statistics Canada data. By February 2019, it had risen another 4.3 per cent to 805,300.

In southeastern Alberta, the numbers have fallen steadily.

Then looking at Calgary and the south, employment has remained relatively flat. Calgary had 861,000 people employed at the start of the recession, which rose to 866,100 by the end of it. In February, it had risen by 3.4 per cent to 895,700.

Tombe said the same factors play into that contrast as do with the age differences: the nature of the jobs in the regions.

Many of the jobs impacted by the downturn of oil in Calgary were headquarters-based, meaning they didn’t suffer the same kind of losses cities like Edmonton saw, where the jobs are more focused on processing, Tombe said.

Impacting the vote

Tombe said the varying success people have experienced in bouncing back from the recession can have a large impact on how they vote, but he said it’s important to note that governments only have “fairly modest effects on an economy’s overall growth.”

“We are too quick to credit the government when things go well and too quick to blame them when things go poorly,” he said, adding that many of the factors that are negatively impacting the economy are out of the province’s direct control.

According to a Global News and Ipsos poll carried out earlier this month, support for the NDP and UCP is nearly tied in Edmonton, but the story is very different in Calgary, with 57 per cent of eligible voters polled saying they’d vote for the UCP and 32 per cent saying they’d vote NDP.

Throughout the rest of the province, 57 per cent of those polled said they’d cast a ballot in favour of the UCP while 30 per cent said they were NDP supporters.

Age-wise, the two main parties were at nearly a tie among the 18-34 range. As the voters polled got older, the support for the NDP fell to 35 per cent in the 35-54 age bracket. Of those 55 and older who were polled, 62 per cent said they’d vote for the UCP with 32 per cent saying they were leaning toward the NDP.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.