From 2006 to 2009, Stephen Harper was prime minister, leading a Conservative government that fended off a Liberal Party that hoped to sweep to power in 2008 on the strength of a “Green Shift” that would cut income taxes and put a price on carbon emissions.

All through that time, Mark Cameron worked as a senior policy advisor in the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO), under a boss who came under heavy criticism internationally for his actions on the climate change file.

Coverage of carbon pricing on Globalnews.ca:

Today, Cameron has a new job, as executive director at Canadians for Clean Prosperity, an organization that works to foster political support for “market-based policies that generate growth while conserving our environment.”

It has just released a new report titled, “Carbon Dividends Would Benefit Families.”

And it argues that, far from just costing Canadians money, a federal carbon pricing plan could actually give more cash back to families than they spent in the first place.

The federal government earlier this year passed the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act, legislation that puts a national price on fossil fuels.

Some provinces — including Saskatchewan and Ontario — have indicated they won’t go along with it.

For provinces that won’t fall in line, the federal government has said it will bring in a “backstop,” a direct carbon tax for those provinces that will begin at $20 per tonne in January 2019 and then rise by $10 every year before hitting $50 in 2022, the report noted.

Under the act, revenues collected from any backstop would have to return to the provinces or territories they came from.

Provincial or territorial governments could take the money, but Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Environment Minister Catherine McKenna have indicated that it could flow right back to households in those jurisdictions, the report added.

Canadians for Clean Prosperity engaged environmental economist Dave Sawyer to look at how much the backstop would cost households in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Ontario, and how much money families of different income levels would be given back.

The report found that, in almost every case, households that paid carbon taxes under the backstop would take back more money than they paid in.

This is because carbon taxes aren’t just collected from households, but from emissions by industries and businesses.

“The results show that at almost all income levels and for almost all family types, families and households would receive more money back in carbon dividends than they would pay out in carbon taxes or indirect costs,” the report said.

The cost of carbon was analyzed two ways — through the taxes paid by households in energy, and indirect costs associated with non-energy consumption.

WATCH: Carbon tax remains sticking point for Canada’s premiers

Indirect costs were calculated by taking household expenditure data from Statistics Canada and then looking at the greenhouse gas intensity of goods and services.

The analysis found that, even when putting carbon taxes and indirect costs together (this was done by Global News, not the report), households still largely took more money back.

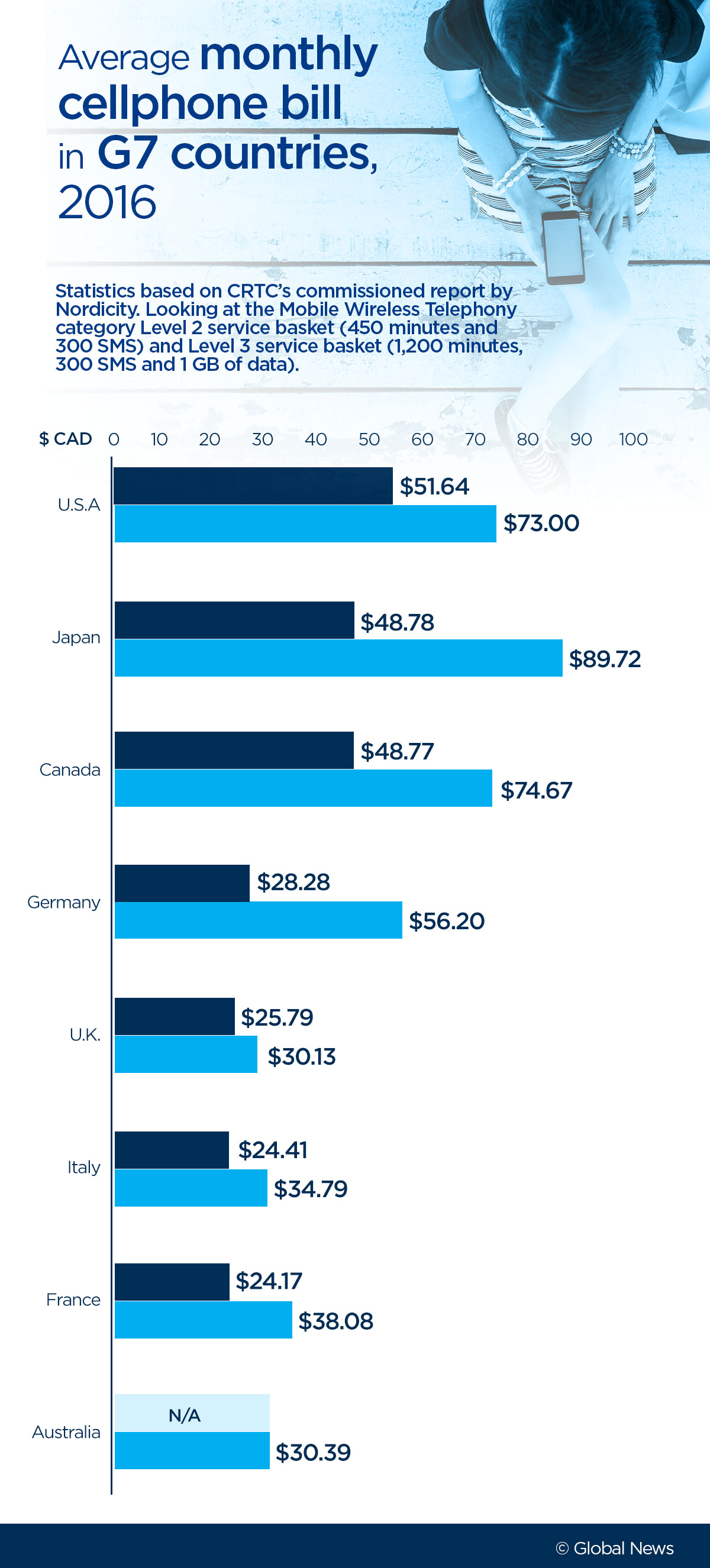

Here’s what the calculations looked like for two provinces, in ranges that captured median total incomes for economic families with children.

Saskatchewan — carbon costs v. benefits, incomes of $100,000 to $150,000

Alberta — carbon costs v. benefits, incomes of $100,000 to $150,000

The returns would be more acute in Saskatchewan, the report noted, than they would be in Ontario.

This became clear when looking at money returned to households per capita.

In the latter, an average Ontario household of 2.6 people would receive $350 per capita next year, while in Saskatchewan, where people use more coal-fired electricity, an average household of 2.5 people would be returned $1,075.

READ MORE: Carbon tax won’t harm economy, but climate change will, study shows

There were variances in how much money households would take back, particularly when looking at their incomes.

The report noted that in Ontario, a household that earned income of over $150,000 would only receive $2 more in carbon dividends than it paid in carbon costs.

However, it also said that lower-income families would receive the biggest benefits, as would families in provinces with more intense emissions, like Saskatchewan and Alberta.

For Sumeet Gulati, a professor of environmental and resource economics at UBC, the numbers looked solid so long as the federal government returns revenues directly.

WATCH: Scheer accuses Trudeau of hiding true costs of Canada’s Carbon Tax

He thinks that’s the best way for the feds to counter anti-tax sentiments in provinces like Saskatchewan and Ontario.

One omission he identified in the report — the analysis did not consider the increased prices of goods due to carbon taxes applied throughout a supply chain.

While he called that an omission, “I do not consider it a significant one.

“Most people care only about direct costs, it is what the political rhetoric is all about too. Most do not associate indirect costs with carbon policy,” he told Global News in an email.

“Finally, I do not think the indirect costs are large enough to change these conclusions.”

As for whether the federal carbon pricing plan could have any effect on emissions, Gulati said it “creates incentives to reduce greenhouse emissions at every level.”

“That is the beauty of per capita lump-sum returns,” he said.

“We still pay a higher price for gasoline or other carbon-based fuels. This keeps the incentives to reduce carbon emissions alive.

“We still drive less, and buy fuel-efficient vehicles in response, but also receive a little more money at the end of the year as a rebate/dividend.”

Comments