Watch the video above to hear how Mallory and Dave Holmes are breaking the silence of early infant loss.

Like most young couples, Mallory and Dave Holmes were looking forward to becoming new parents. But 20 weeks into the pregnancy, they received devastating news.

An ultrasound revealed their baby girl had a rare and lethal form of dwarfism.

“There was nothing they could do to save her,” Mallory Holmes, 30, told Global News.

“So we had the choice of carrying her to term and meeting her, which we chose because she was our daughter and we fought hard to have her.”

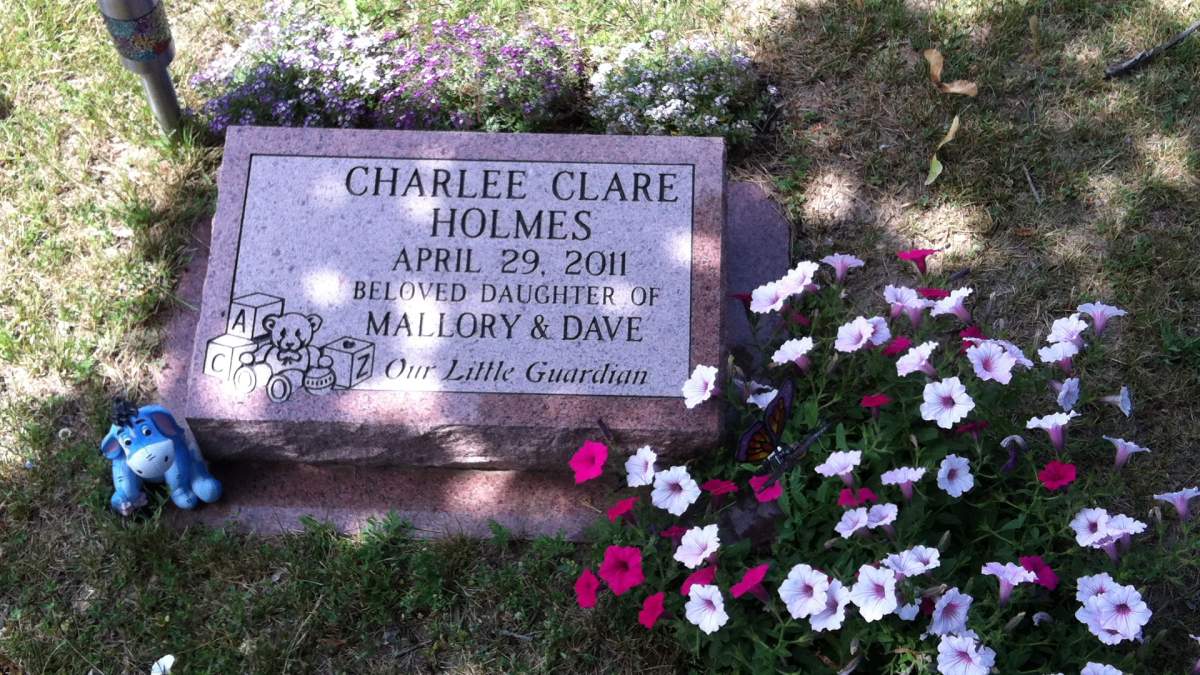

On April 29, 2011, Charlee Clare Holmes was born.

READ MORE: A parent’s worst nightmare — SUDC, cousin of SIDS, claiming lives of children

“She was just over a pound, tiny and beautiful, but sadly the same day we had her was the same day we had to say goodbye and it was one of the hardest things we’ve had to go through,” Holmes said.

“It was the most depressing joy. I don’t know how else to describe it,” explained her husband Dave, 30.

“I had waited so long to meet her. There was a part of me that just did not want to remember what I had been told by doctors.”

The Holmes were told that Charlee would likely not live for longer than 10 minutes, but in fact she lived for just over two hours. The couple said they filled those two hours with as much love as possible.

“I can’t even remember blinking. She probably knew more love than most people do,” Mallory said.

“I don’t think I’ve ever kissed a human as much as I did. Just looking at her features and trying to remember them.”

Dwarfism and other fatal neonatal conditions

While there are other survivable forms of dwarfism where people can live full and healthy lives, the kind of dwarfism Charlee had, as doctors put it, would not have been compatible with life.

“Charlee’s bones weren’t formed correctly and she was going to be very, very small and short,” explained Michelle Gordon, chief of neonatal and pediatric medicine at Orillia Soldiers’ Memorial Hospital, where Charlee was born.

“When babies have this condition, their lungs don’t develop properly, they can’t breathe properly and it’s not a condition babies can live with once they’re born.”

READ MORE: What’s killing babies in Canada’s North?

It was caused by genetic factors, but not something that was inherited from either Dave or Mallory’s families.

“All of us are made up of genes that are like our blueprints. They tell us what colour our eyes are going to be, what our hair colour is going to be, how tall we’re going to be, whether we’re going to look like mom or dad,” explained Dr. Gordon.

“Sometimes there’s a problem with our chromosomes or genes and that creates a problem with the way the body is formed. Sometimes you inherit it from mom or dad and sometimes, like in Charlee’s case, it just happens spontaneously when the fetus is being created.”

And while Charlee’s condition was rare, early neonatal mortality, which is the death of a child under one week of age, does happen in Canada.

According to Statistics Canada, there were 1,153 early neonatal deaths in 2015 alone.

Dr. Gordon said there are a number of different conditions that could cause a baby to die so soon after birth.

“Some examples are other chromosome problems like extra chromosomes or parts that have been taken away,” she explained.

“Others are very serious heart problems. Sometimes babies are born with brains that are not properly formed. There’s a whole list of conditions that can be found when couples are pregnant and many of them would only be detected later on.”

Stigma and coping with the loss

After saying goodbye to their firstborn child, Mallory and Dave said they experienced immeasurable loneliness and darkness.

“Coming back to the nursery and having to deal with an empty crib, and the painted walls,” Mallory said. “Having to paint over those walls for our next child was one of the most heartbreaking things we’ve ever done.”

She admitted that even after she knew about Charlee’s condition during the pregnancy, she felt the need to finish the nursery.

“Looking back now, I see that it was a coping mechanism. At the time it was – we’re going to have a baby, finish the nursery, put up her name, put those leopard print shoes on the shelf, because that’s what she’s going to come home and wear. You’re not thinking logically,” Mallory explained.

Get weekly health news

Dave said one of the most difficult parts was also feeling that they couldn’t speak to anyone about what happened.

“We hadn’t talked to anyone, or even heard of anyone else in our family or friends who had lost a child or had a miscarriage, any type of prenatal loss,” he said.

The problem, they believed, is that no one really knew how to speak to them about it.

“When you talk about someone passing away, there’s an acceptable language to it. You can say I’m sorry for your loss, they’re not suffering anymore but when you lose a baby or pregnancy, it can silence a room.”

Mallory added that by not saying anything at all, it makes parents feel like they can’t talk about it because they make other people feel uncomfortable.

“There is also a stigma,” she said.

“You feel that if you say you’ve lost a child, you’ve failed as a parent. That’s the one thing you’re suppose to do is keep your child alive.”

Guilt is a feeling that Dr. Gordon said is common for parents and especially moms to experience after losing a child.

“They begin blaming themselves,” she said.

The reality is though, “the vast, vast majority of the time, it just happens.” And there was nothing a parent could do to prevent such a tragedy.

Eventually, the couple found a bereavement group, which they attended once a month for several months, just to talk to other parents who had experienced a loss.

Talking about it is what helped them with their grief the most.

They said parents can’t do it on their own, they need a community of people to help them with the grieving process.

The government can also play a role, according to Conservative MP Blake Richards.

Currently, in Canada parental leave benefits cease immediately upon the death of the baby.

Richards tabled a non-partisan private member’s motion in Parliament aimed at “fixing a serious flaw” and helping parents who suffer the loss of an infant child.

READ MORE: Parents who lose their baby being forced back to work too soon: Conservative MP

“The idea of Motion 110 is to have a committee study the issue of infant and pregnancy loss and come up with a way to ensure these programs, particularly the employment insurance program, don’t just add this extra grief and stress on families,” Richards told Global News.

“And it doesn’t force them back to work in the days following their child passing that they actually have a chance to grieve properly and not have financial stresses added at that time.”

The motion will return to the House for second debate in early June, where it will go to vote.

The decision to have more kids – second child falls sick

A year and a half after Charlee passed away, Mallory and Dave decided they were ready to have another child but the decision didn’t come easy.

The couple was worried about the possibilities of losing another child and told themselves they could not survive going through something like that again.

At the same time, they said, they had so much love to give, they could not delay having more kids.

“I think it had to do with how much we loved her. That love you have for your child is, you can’t put that into words,” Mallory explained.

“I remember us both saying if we are lucky enough to have another child that survives and is healthy, we will do anything to make their wildest dreams come true and that was a sense of hope for us, knowing that we have more love to give. We wanted to have more of that in our lives.”

Mallory was closely monitored by doctors throughout the entire pregnancy and in August 2012, they welcome their son Keenan into the world.

To their relief, he was born healthy and the family was able to go home from the hospital without any complications.

But at two weeks old, Keenan fell ill with a kidney infection that wasn’t caught at birth and he was admitted into the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) back at Orillia Soldiers’ Memorial Hospital.

“We almost lost him,” Mallory said.

If they didn’t get Keenan to the hospital when they did, he may have not survived.

“We spent 11 days in the hospital, 11 very very hard days, very long days,” Dave said.

Mallory recalled the two feeling completely helpless.

“We just kept saying, we can’t do this again, like physically, we cannot survive another loss that’s blindsighting us this time. We’re not going to make it.”

Keenan eventually recovered and grew up to be a healthy boy but not without his parents watching his every move.

“I would just watch him sleep, I don’t think we slept for months,” Mallory said with a laugh.

“He wasn’t allowed to run on pavement, we were very paranoid and we spent many trips to the ER just having them check him.”

Four years later, they had another healthy boy, Mackenzie.

The parents made it a point to explain to their boys that they once had a big sister, named Charlee.

And at 5 years old, Keenan knows to call himself a proud little brother.

“At orientation in Kindergarten they asked, how many brothers and sister do you have, he had no problem saying, I have a little brother Mackenzie and I had a big sister named Charlee but she died,” Dave said.

“He’s learning that it’s okay and we want him to continue that.”

Charlee’s Run

The family has made it their mission to keep Charlee’s name alive and to commemorate her legacy.

Often times, Dr. Gordon explained, parents don’t get an opportunity to talk about a child they’ve lost.

“It’s like that member of their family never existed,” she explained.

“It’s very important for families to have an opportunity to talk about their child and acknowledge that they were a member of their family.”

With that in mind, as well as a need to show gratitude towards the NICU at Orillia Soldiers’ Memorial Hospital, a charity event known as Charlee’s run was born in 2017.

“We realized we were doing something bigger than just a run. We started getting messages from other parents who had lost a child,” Mallory said.

Charlee’s Run turned into something much bigger than a fundraiser, it became an outlet for the community to come together to remember and celebrate the lives lost too soon.

“We were giving a voice to people who didn’t have a voice before, which is really to raise awareness for pregnancy and infant loss.”

The first event drew nearly 400 people and raised over $40,000, which was used to fully renovate the unit.

After such an overwhelming response, the family decided to make the run an annual event.

“It was such a celebration of Charlee’s life, and it became a recognition of a really important issue in our community and it was truly a beautiful event,” said Dr. Gordon.

This year, they raised $57, 500 for the construction of the hospital’s new Paediatric outpatient unit.

“Just saying her name, Charlee, feels really good. And giving other people that chance, gives them healing and helps them feel as good as we do,” Mallory said.

“The more you talk about it, the more you realize there are so many more people going through the same thing and, as it turns out they thought they couldn’t talk about it either.”

A lifetime of struggle

While the Holmes family have found ways to cope with such a tragic loss, they admit, some days are still harder than others.

“Be aware of the triggers, pregnancy due date, Mother’s day, Father’s day. Any holiday,” explained Mallory.

The couple’s trigger relates to the first gift they bought for their baby, when they found out they were having a girl, leopard print shoes.

“I’ll see a girl in leopard print shoes and that will set me back.”

Dave added, “in a crowd of a thousand people I will find those leopard print shoes.”

On days like those, they said they don’t quite know how to move on from that heart sunken feeling.

But thinking of the positives they turned Charlee’s legacy into, helps them get through it.

“I think we realize now that this is a lifetime of struggle and the grief is never going to get easier, it’s never going to get easier to say her name. It’s seven years later and it’s still not easier. Talking helps,” explained Dave.

“The loss of a child is not something you get over, but something you can carry on with.”

Comments