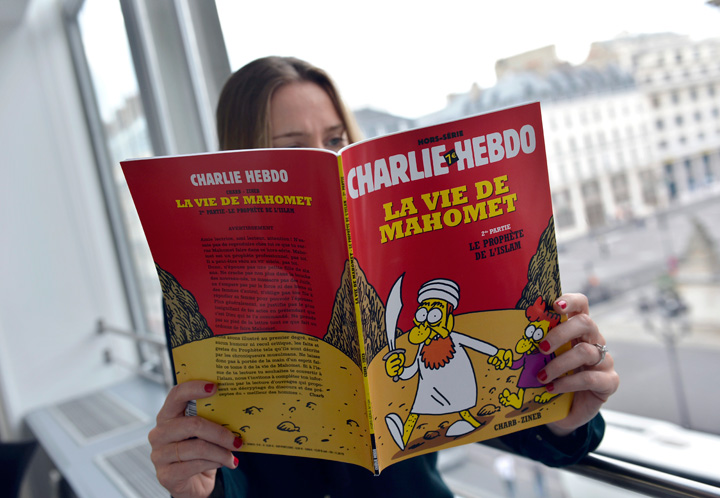

TORONTO – French magazine Charlie Hebdo was threatened for years over its religious cartoons mocking the Prophet Muhammed, culminating in a horrific attack on the publication’s Paris offices that left 12 people dead. Editor Stephane Charbonnier lived under police protection for years, and the office was firebombed in 2011 after featuring a caricature of the prophet on its cover. So why did these cartoons lead to such a tragedy when cartoonists have been satirizing religion for years?

“Of course religion has consistently been a target of satire,” York University associate professor Julia Creet told Global News. “Even Charlie Hebdo itself published scurrilous satires of the Catholic Church and its opposition to homosexuality.

“One of the earliest French satirists, Rabelais, was a monk who mocked everything. South Park has pilloried every religion in the world, though they only received death threats after daring to depict Muhammad. But, there are bigger contextual questions that must be asked in this circumstance that have to do with the relative power of the targets.”

Creet provided one example of an anti-Catholic cartoon dating back to 1851:

The above was printed in Punch, a Victorian periodical, on March 29, 1851. The cartoon was in response to “a dispute over the installation of a rich heiress in a Roman Catholic nunnery,” according to a paper by Dominic Janes published by The Johns Hopkins University Press. It accuses the Catholic Church of greed by “alluding to the criminal practice of kidnapping girls for their clothes” and also invites readers to “imagine the priest stripping the young girl” of her dress when she enters the convent, writes Janes. The author suggests it showed Punch‘s shift toward anti-Catholic attitudes to “achieve mainstream acceptance.”

- Arrest made after police issue emergency alert about ‘dangerous man’ in Bible Hill, N.S.

- 3-year-old Elijah Vue still missing: Man pleads not guilty to child neglect

- Closing arguments presented in Michael Gordon Jackson abduction case

- Trump trial seats 12 jurors after dismissing 1 over media reports on her ID

Here are some more contemporary examples highlighted by Creet, who teaches a course on satire and lectured on Charlie Hebdo this week:

Pat Oliphant’s above cartoon was published in December 2008 on washingtonpost.com and prompted complaints from over 300 readers who “said he lampooned their faith,” according to Washington Post ombudsman Deborah Howell. The cartoon shows then-vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin speaking in tongues — an aspect of worship in some Pentecostal churches.

“Anybody who holds deep religious beliefs is going to be offended by any kind of satire that attacks their spiritual symbols,” said Creet. “But we know that parts of Islam are in a particularly fraught moment. We know there are these huge tensions between Muslims, and Christians, and Jews.”

Satire works in a way that is always dependent on a particular historical and cultural context, says Megan Boler, professor of education and media at the Ontario Institute of Studies in Education (OISE) at the University of Toronto. She teaches classes on satire, and says it works on two levels: the joke and the “unspoken” or “unsaid.”

“That unsaid will always have to do with a particular moment or particular cultural myth that does require context in order to understand,” she said. “It’s also dependent on hierarchies of status in our society. So it’s more acceptable to make fun of certain groups and risk stereotyping certain groups than it is with other groups at a particular given moment.”

France has the largest Muslim population in Europe, and a “sizable portion” is fairly marginalized in French society, said co-director of the Canadian Network for Research on Terrorism, Security and Society Lorne Dawson in a Wednesday interview with Global News related to the suspects in the Charlie Hebdo attacks.

“So unlike the Muslim populations in Canada and the United States that are pretty well-integrated and assimilated, the French Muslim population is pretty ghettoized, and they are economically not in good shape,” he said. “You have a really substantial portion of young Muslim men who have not very good prospects in life. So we do have prime conditions for recruitment to radical causes.”

The above cartoon was published in the issue prior to the attack, called “Still No Attacks in France.” It shows a caricature of an extremist fighter saying “Just wait – we have until the end of January to present our New Year’s wishes.”

When asked if Charlie Hebdo‘s cartoons of the prophet Muhammad are comparable to the Nazi cartoons of the 1930s that satirized Jews by reinforcing stereotypes, Boler said there are similarities, but they are two distinct historical contexts.

“By looking at the contexts, we’re able to see how a culture will change the norms of who is permissible to make fun of.

Charlie Hebdo‘s controversial use of satire has made headlines since the attack: Vox’s Max Fisher asks “Are Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons racist? Did they go a step beyond satire and become something uglier?” Glenn Greenwald questions the #JeSuisCharlie push for a “very selective application of free speech principles.” Greenwald pointed out that while thought of as an “equal opportunity” offender, Charlie Hebdo fired one if its writers for writing a sentence some said was anti-Semitic; that writer later won a judgment against the magazine for unfair termination.

Creet called Charlie Hebdo “astonishingly left” in its politics, but believes people are still trying to work out the intention behind its controversial cartoons.

“The potential is always there for satire to be misread,” added Creet. “Because it demands on the part of the observer/reader/viewer, that the reader understand the intentions. It’s one of few places where intention still matters for writers, readers, drawers.

“How is it possible to read these images? It’s possible to read them as wickedly racist or as ardently non-racist, but that is the nature of satire.”

Comments