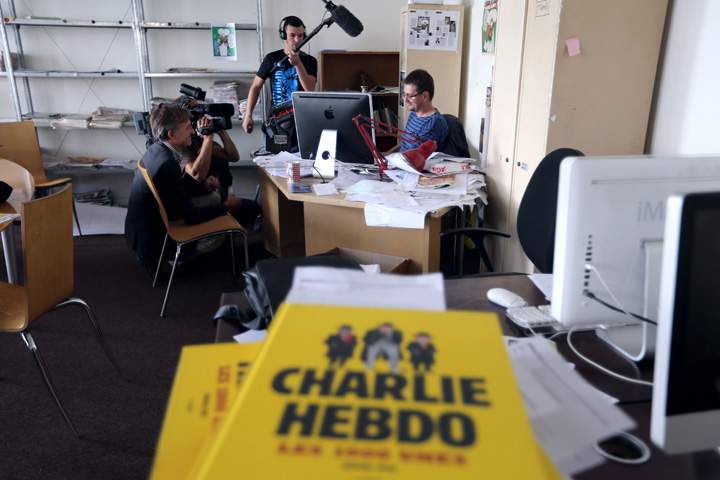

WATCH ABOVE: The satire magazine Charlie Hebdo wasn’t well known outside France, but its cartoonists and writers helped shape a generation in that country. They had been threatened before, but they never gave up and they never gave in. Eric Sorensen reports.

TORONTO – After years of drawing attention for ridiculing sensitivity around the Prophet Muhammad, the offices of French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo were attacked Wednesday morning, with at least 12 people killed in the shooting.

French President Francois Hollande called the tragedy “a terrorist attack without a doubt,” and said several other attacks have been thwarted in France “in recent weeks.”

Minutes before the attack, the official Charlie Hebdo Twitter account posted a satirical cartoon of the extremist Islamic State group’s leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, giving New Year’s wishes.

Another cartoon released in this week’s issue and entitled “Still No Attacks in France” had a caricature of an extremist fighter saying “Just wait – we have until the end of January to present our New Year’s wishes.”

Charlie Hebdo has been repeatedly threatened for its caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad and other controversial sketches.

In 2006, the magazine reprinted caricatures carried by a Danish newspaper in 2005 that stoked anger across the Islamic world. Many European papers reprinted the drawings in the name of media freedom.

Charlie Hebdo has also faced legal challenges; it was acquitted in 2008 by a Paris appeals court of “publicly abusing a group of people because of their religion” following a complaint by Muslim associations.

The weekly’s offices, located on the northeast edge of Paris amid a cluster of housing projects, were firebombed on Nov. 2, 2011 after a spoof issue featuring a caricature of the prophet on its cover. No one was injured in that attack.

The above front page, subtitled “Sharia Hebdo,” is a reference to Islamic law. The magazine’s offices were destroyed in the firebomb attack just hours before the edition hit newsstands.

Nearly a year later, the publication again published Muhammad caricatures, drawing denunciations from around the Muslim world. The government defended the right of the magazine to publish the cartoons, which played off of the U.S.-produced film The Innocence of Muslims and ridiculed the violent reaction to it. Riot police took up positions outside the offices of the magazine on Sept. 18, 2012, when the caricatures were published.

WATCH: French President Francoise Hollande condemns attack on Charlie Hebdo offices calling it an “act of exceptional barbarity.”

One of the cartoonists, who went by the name Tignous, defended the drawings in an interview with The Associated Press at the time.

“It’s just a drawing. It’s not a provocation.”

But members of the Muslim community disagreed.

“People want to create trouble in France,” President of the Paris-Based Anti-Islamophobia Observatory Abdallah Zekri said at the time.

“Charlie Hebdo wants to make money on the backs of Muslims.”

Charlie Hebdo’s chief editor Stephane Charbonnier, who went by the name of Charb and lived under police protection for years, defended the cartoons.

“Muhammad isn’t sacred to me,” he said in a past interview with the AP. “I don’t blame Muslims for not laughing at our drawings. I live under French law; I don’t live under Quranic law.”

Charbonnier was among the 12 people killed in Wednesday’s attack.

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) called the rampage “a brazen assault on free expression in the heart of Europe” and British Prime Minister David Cameron tweeted his support for freedom of speech.

The incident comes the same day of the release of a book by a celebrated French novelist depicting France’s election of its first Muslim president. Hollande had been due to meet with the country’s top religious officials later in the day.

With files from Adam Frisk

Comments