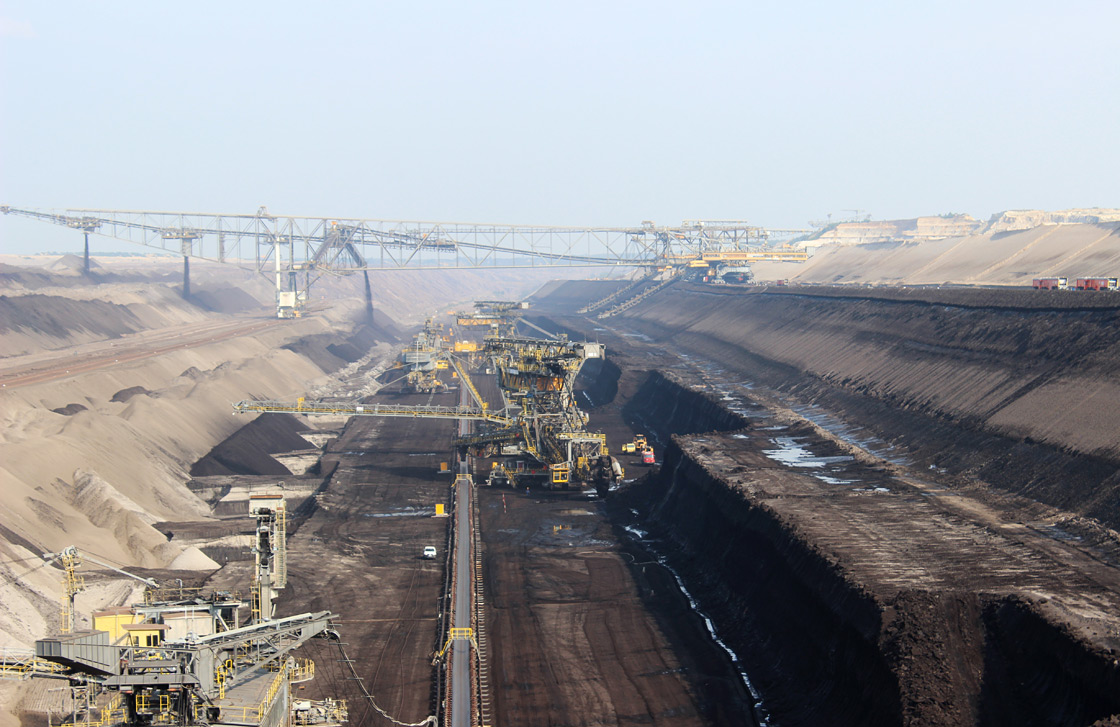

The bus bumped up over the hill and the tourists inside gasped out loud. They crammed onto the right side of the vehicle, eagerly snapping photos of the wasteland spread before them.

They were looking at a hole in the ground – the Welzow open-pit coal mine in Brandenburg state, one of Germany’s many working lignite coal mines. The mine is massive: a pit covering 88 square km, so deep your ears pop as you drive to the bottom.

Since announcing its “Energiewende” or “energy transition” in 2011, Germany has modelled itself as a global model of green energy made reality.

But Germany doesn’t run on sustainable energy alone. While the country is a world leader in solar power, it is also the world’s largest producer of electricity from lignite coal. And it’s one of the few that’s actually using and producing more coal each year – not less.

Germany has set ambitious targets for green electricity generation – 35 per cent of electricity consumption by 2020, and 80 per cent by 2050, is meant to come from sustainable sources such as wind and solar.

But reaching those targets means dealing with its lignite industry – a lucrative, centuries-old sector that employs thousands of people, generates massive amounts of stable electricity, and sent some 181 million tonnes of climate-damaging carbon into the air last year.

When it comes to adding green energy to its mix, Germany has made impressive progress in just a few years.

Solar is growing. So are wind and biomass. On one day – June 9, 2014 – Germany was over 50 per cent powered by renewable electricity, according to media reports – quite a feat for a modern, industrialized nation of 81 million people. The country has broken several records for green electricity use over the past year.

But this is accompanied by a much more rapid shift in energy use: Prompted by the Fukushima disaster in Japan, the former nuclear-energy giant is phasing out nuclear entirely. Eight plants were closed in 2011. Germany’s nine remaining reactors are to go dark by 2022.

These goals have received widespread support among the German public as well, according to recent polls. A recent survey by TNS, published in the newspaper Die Welt October 7, 2014, reported that two-thirds of Germans rated the Energiewende as good or very good – though they were less impressed with the government’s implementation of the plans, with only 21 per cent saying the Energiewende has been well-managed.

And a December 2013 survey by Deutsches Atomforum, the German nuclear industry association, found that 81 per cent of people thought generating electricity through renewable energy was important or very important.

But at the same time, Germany is relying increasingly on a much dirtier electricity resource: coal.

Germany has significant deposits of lignite coal – a soft, crumbly form of the fuel that has low carbon content, high water content and pollutes even more than black coal.

And since the Energiewende was announced in 2011, lignite electricity generation increased to its highest level since 1990.

According to numbers released by Germany’s Finance and Energy Ministry, lignite coal was Germany’s biggest source of electricity in 2013. An extra 15 terawatt hours of lignite generation were added between 2010 and 2013 – about the same amount of growth as wind power over the same time period.

This has a big effect on the country’s carbon emissions: Germany’s carbon emissions ticked upward in 2012, due partly to lignite coal, though preliminary figures from 2013 show a slight decrease in emissions from that energy source.

Canada’s electricity generation by comparison is quite green, due mostly to our hydro resources. About 63 per cent of Canadian electricity was generated from hydro in April 2013, according to Statistics Canada. But coal is still a significant source for power, particularly in Alberta. While it provides only about 15 per cent of Canada’s electricity supply, coal accounts for 11 per cent of the country’s overall greenhouse gas emissions, according to Environment Canada.

It remains an open question whether Germany can green its energy and keep its coal.

Either way, the implications could be great for Germans whose lives are tied up with that crumbly brown mineral.

“Our municipality will die”

GALLERY: Click the arrows to explore photos of Kerkwitz, Germany

Sleepy, picturesque Kerkwitz has occupied the same spot in the Lusatia region of former East Germany, about a two-hour drive southeast of Berlin and four kilometres from the Polish border, for five and a half centuries.

A decade from now, it may be gone.

The tiny village has been slated for demolition because of what’s underneath those gardens: coal.

The electricity and mining company Vattenfall, owned by the Swedish government, wants to dig a new coal mine in the area and the Brandenburg state government is considering the proposal, though details have yet to be worked out. If the mine is approved, the inhabitants of Kerkwitz and nearby towns Atterwasch and Grabko (about 900 people in total) will have to move somewhere else.

The plan was first announced in 2007 but very little is concrete yet. If the mine is built it’s Vattenfall’s responsibility to relocate displaced residents – but they themselves have no idea what will happen to their villages, when they’ll be uprooted or where they’ll go.

“We cannot plan anything. We have no idea what to do, to build a house or not. … Many question marks,” said Kerkwitz resident Jessica Sroka, 23.

“It is all up in the air, for years an uncertain situation. That is the worst,” said Tony Lehmann, who lives in Kerkwitz and works as a mechatronics technician for the mining industry in the nearby city of Guben.

Get daily National news

“If we knew really, okay, we need to move, we would at least know. It would not be nice but at least it would be calming.”

Andreas Stahlberg works in mining-related issues for the Schenkendöbern municipality, which includes the threatened villages of Kerkwitz, Atterwasch and Grabko.

The municipal government opposes the expansion not just because people will lose their homes, but also because it’s damaging to local quality of life, he said.

“We think that when three villages will be resettled, our municipality will die.”

That said, living near these mines is no picnic either, he said.

“When you want to go in an outside area in the gardens, it’s not possible sometimes. Washing clothing, drying clothing outside is often impossible. It’s hard when you live quite near.”

He and local residents, as well as thousands of other activists from elsewhere in Germany and abroad, joined hands in August in an eight-kilometre-long human chain through affected villages and across the German-Polish border to protest the coal mine expansion. They plan to fight to keep Kerkwitz and other settlements where they are.

Villages elsewhere are slated to move, too, as at least three new mines or mine expansions are planned.

Proschim is one of them. It sits near the massive Welzow Süd mine. The Brandenburg government has approved a new mine development there and is working with Vattenfall on the next stage of the licensing process.

“I have lived in Proschim 60 years. I was born in Proschim,” said Petra Rösch, who owns a beef and dairy farm and was until recently the village’s mayor.

“For me, it’s my home.”

She has no plans to move, and, according to media reports, as mayor she completely refused to discuss the issue with Vattenfall.

“We don’t need to think about what will happen after if the coal mine comes, because it will not come,” she told Global News.

It’s clear others in Proschim disagree, however: According to local media reports Rösch lost the last local election to Gebhard Schulz, a Vattenfall employee.

Out with the old, in with “New Haidemühl”

GALLERY: Click the arrows to explore photos of old and new Haidemühl, Germany

Mines – and the villages they displace – have come and gone in Lusatia before. One local museum chronicles the destruction of 136 villages in the region since 1922, many of them home to the Sorbs – a cultural minority. More than 25,000 people had to move, according to the museum’s records.

One such village was Haidemühl, near Proschim next to the Welzow Süd mine. In 2006, more than 600 residents left. Most moved into a new community – “New Haidemühl” – which Vattenfall build especially for them on the outskirts of a nearby town.

The old village now stands, in ruins, on the edge of the mine – waiting to be swallowed up.

According to Vattenfall spokesperson Thoralf Schirmer, every Haidemühl resident who chose to move to the new village was given a home comparable to what they left behind in square footage and amenities. If you had a three-bedroom house, you got a three-bedroom house, no matter what the difference in market value would be.

“New Haidemühl,” about 14 kilometres away, looks at first glance like a typical North American suburb. As seen from a viewing platform – not an “observation tower” Schirmer says – in the community park, there are lots of green lawns and tiny, scrubby trees. It’s quiet on a Wednesday morning, with few cars or people around.

Schirmer points out a community centre, a fire station, even a large pond dug for the local anglers club.

“We had to replace everything that the community used to have at the old place, at the new place. This is one of the principles,” he said.

He said Haidemühl residents who chose instead to move to other towns or to move in with their adult children were compensated financially.

But they all had to move somewhere.

Once the state government decides a village has to go, residents no longer have a say. If they don’t cooperate their land could be expropriated, and they could be obliged to accept whatever terms are offered.

“In the cases I know from former resettlements, it was not necessary to use any legal instruments to make them move,” Schirmer said.

“But it was all talks, long talks, negotiations, and then a fair solution for both sides. There was no case of compulsory purchase. It was not necessary to use this instrument of compulsory purchase, but this would be the last resort.”

Over lunch at the Schwartze Pumpe lignite power plant, talk turns to Proschim.

“It’s really a pity to move such a pretty village,” Schirmer said. But this isn’t up to Vattenfall, he says: The company does what the government decides.

Coal mining has meant the landscape of Lusatia is constantly being transformed by mammoth-scale human activity.

The mines themselves, each several square kilometres in size, slowly creep sideways along the coal bed at a rate of about 300 metres per year, as machines chew up the earth on one side and fill it back in on the other. Once the coal is gone, the machines leave a huge hole ringed by desert-like slopes.

According to Vattenfall, about 860 square kilometers of land in Lusatia have been at some point affected by mines. That’s about the size of Ontario’s Brant County – bigger than Alberta’s oilsands.

Right now only about 315 square kilometres are being actively mined – more like the size of Saint John, New Brunswick, or Surrey, BC.

So far, 14 former mines have been filled with water to form artificial lakes – a process the local tourism board says will eventually create the largest artificial lake district in Europe, with 24 lakes total. On its website, the tourism board offers cycling tours and promotes boating and other activities in the area, with many lakes even open for swimming.

Forests are being replanted where land has been disturbed by mining. Vattenfall plans to plant an appropriate mix of native trees, Schirmer said; previous replanting efforts in the Soviet GDR-era resulted in a pine forest monoculture, not native to the area.

“It is not only about destroying but is also a chance for creating,” he said.

Agricultural land has also been re-made, including a vineyard Vattenfall built in 2005 on land formerly part of the Welzow mine.

“This region in medieval times used to have vineyards,” he said – just look at all the streets named “Vineberg.”

“So you can recreate all this and you can show people that it’s possible, even in this rough region, to grow, I won’t say excellent wine, but good wine.”

The result of all of these projects is that the post-mining landscape of the Lausitz bears little resemblance to whatever was there before. There are new lakes, new forests, new towns, new vineyards.

“It looks different. Of course it looks different,” Schirmer said. And, he argues, “It can be a benefit for the country, the landscape.”

Welcome to Welzow – City on the mine

GALLERY: Click the arrows to explore the Welzow lignite coal mine

Welzow is the kind of place where old women ride bicycles to the bakery every morning with wicker baskets dangling from their handlebars, where most houses have lace curtains, and the distant rumble of the mine – sounding something like a train passing – is constant, and even more noticeable at night.

The city’s motto, displayed on its website, is “Stadt am Tagebau” – “City on the mine.”

Lusatia is a comparatively poor region of Germany. The mining and energy sector makes up the biggest share of local industry.

According to the Brandenburg state government, the coal industry provides more than 10,000 direct and indirect jobs, 40 million euros a year in tax revenue and 1.3 billion euros in economic benefits.

That’s partly why the state of Brandenburg supported the new Welzow mine, which would displace about 810 inhabitants.

“The Government takes very seriously, that people lose their homes if the coal is mined,” wrote state spokesperson Steffen Streu.

“Nevertheless the provincial government has carefully considered its decision. This process took several years.”

He said producing electricity from brown coal is an “indispensable” bridging technology to accompany Germany’s energy revolution, security of supply, system stability and affordability (in contrast to green energy, whose supply is often unpredictable).

“The brown coal secures jobs and added entrepreneurial value creation. Also, the brown coal as an indigenous energy source ensures independence from energy imports,” he wrote.

And while, in response to queries from Global News, the Brandenburg government said the intention is for lignite to eventually become unnecessary, it gave no time frame for phasing it out. Renewable energy is supposed to account for 80 per cent of the country’s gross electricity consumption by 2050 but there’s no indication how this will happen.

“A simultaneous exit from nuclear energy and coal is … not possible”

GALLERY: Click the arrows to explore lignire power plant Schwarze Pumpe

When it comes to coal’s importance, the federal government would seem to agree.

“A simultaneous exit from nuclear energy and coal is … not possible in a highly industrialized country like Germany,” wrote Beate Braams, press officer for the federal ministry of economics and energy, in an email to Global News.

“It is clear that conventional power plants must continue to adapt to the requirements of our energy transition.”

Greenpeace’s Anike Peters doesn’t see it that way.

“Renewables already supplied 28 per cent of electricity in the first half of 2014. So by 2030 or something like that, there will be a much higher supply of renewables, so there is no more need for new coal,” she said.

And calling lignite a “bridging technology” implies that it will end at some point.

“Germany does have climate goals and if Germany wants to reach these goals, there has to be a phase-out of lignite sometime,” Peters said. “And this sometime has to be after our calculations in 2030. After that there is no place in the Germany energy system and no place if you face climate change for new lignite.”

It seems even Vattenfall no longer believes in a future for lignite in Germany: It recently announced its intention to sell German lignite mines and power plants . But Vattenfall stated that the application process to expand the mines is ongoing, regardless.

But if lignite mining has an expiry date, what happens to the thousands of people whose livelihoods depend on it?

“It’s very important to this region for jobs,” said Paul Zuchold, a 31 year-old Vattenfall worker and Welzow resident who supports the new mine. He drills holes for water drainage in the surrounding mines. Without the mines, he said, “Nobody knows” what people would do for work.

“The mine will go for 30 or 40 years, and then we will see.”

Alexander Brux, a Welzow resident and contract worker for a heating company, agreed.

“In this region there are not many job opportunities,” he said. “Once there were over 7,000 residents. 7,000! Now we’re only about 3,800 who still live here. They all moved, because here there are no jobs and they hoped to find jobs elsewhere. The companies who used to be here all went bankrupt or were marginalized.”

“What are people supposed to do when the power station closes one day and the mine business has become past? Nobody knows.”

Editor’s note, Nov. 12, 2014: An earlier version of this story stated that Germany is using more lignite than ever, which is not true, as lignite use was higher in much of the 1980s and part of the 1990s. Additionally, a decimal point in one figure was in the wrong location. We regret the errors.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.