The City of Vancouver’s ambitious plan for the Downtown Eastside goes to council Wednesday and there are concerns about whether the plan is the right solution for the troubled neighbourhood.

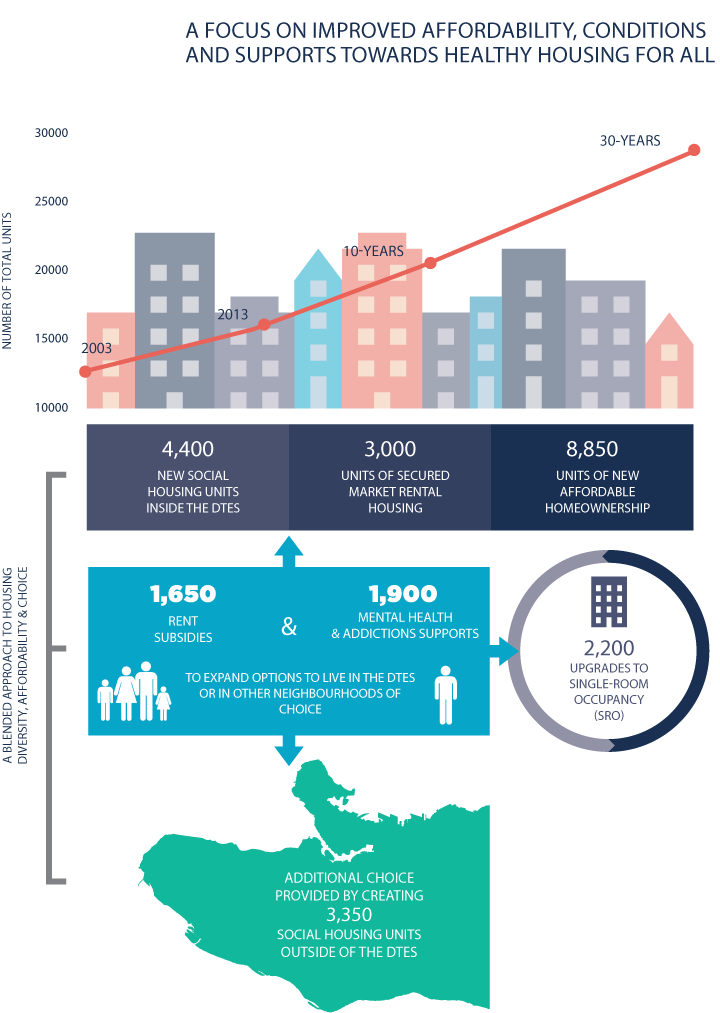

The 300 page plan maps out development in the area east of the downtown core for the next 30 years, while striving to preserve the neighbourhood’s low-income community.

The neighbourhood, running east from Richards to Clark and south to Terminal, is home to 18,500 residents, 67 per cent of whom are considered low-income. The median income is only $13,691, compared to $47,299 city wide.

For the first time, the city is proposing a social and rental housing district in the core of the neighbourhood, called the Downtown Eastside Oppenheimer District, which measures about 40 blocks in the area, roughly surrounding Oppenheimer Park. New projects built beyond existing zoning will be required to contain 60 per cent social housing and 40 per cent “secured market” rental housing.

The plan limits condo development, something city officials say is necessary.

“We want to secure assets for the low-income community,” says city councillor Andrea Reimer. “If you create a rezoning policy that allows market condos or social housing, you know where the land value is going to go — it’s going to go to the condo side — and it becomes impossible to build social housing.”

Reimer says that by discouraging land speculation in the area, private developers may be more willing to build social housing.

“The economics on that are pretty razor thin. It’s challenging but not impossible to get the social housing built, but because it’s so thin, it means no one will be speculating on that property because there’s no profit. If it’s already razor thin, there will be no speculation on the property.”

Victory Square, Gastown, Chinatown and the residential streets of Strathcona will see minimal changes under the plan. A new mixed neighbourhood, with hundreds of condos, is proposed for the area west of Clark Drive near the Ray Cam community centre.

Architect and developer Michael Geller says an exclusive social and rental housing district in the core of the community will only exacerbate the neighbourhood’s challenges.

“My concern is that rather than dilute the concentration of social housing and other housing for people with mental illness and addiction, the plan actually proposes a further concentration of social housing.”

Geller says that the plan could actually prevent new businesses from opening up and filling some of the empty storefronts, because of its policy that new businesses should be accessible to the neighbourhood’s predominantly low-income residents.

“One of things that bothers me is all those derelict storefronts along Hastings Street,” he says. “The plan discourages private developers from fixing those up and filling them with businesses that would cater to people at large. The plan says that — if you read between the lines — ‘we don’t want any more Pidgin restaurants, what we want are shops and services that are acceptable to the local residents, not businesses that will appeal to a city-wide clientele.'”

Geller says his biggest concern is that the plan won’t actually accomplish what it sets out to do: build more social housing. He predicts the plan will have to be revised again, or thrown out completely.

“I predict that if it is approved — and it probably will be with very minor modifications — it will be changed in three years when the first formal review is mandated to take place. They will realize that the housing they were hoping would be built, and the vacant shops they hoped would be filled — is simply not happening.”

Get daily National news

Reimer says the city needs to put the brakes on property values in the neighbourhood and a project like Woodwards, widely considered a successful development mixing condos, social housing and retail, would be detrimental in this area of the Downtown Eastside.

“A project like Woodwards in the Downtown Eastside Oppenheimer District would encourage speculation. We’ve had a 303 per cent increase in property values in the Downtown Eastside in the past 10 years. In the last year, it’s gone up again in the Downtown Eastside, and I’m guessing that’s in anticipation of a plan that would allow for some new condo development.”

Geller says the city shouldn’t be discouraging mixed buildings that include market condos and social housing under one roof.

“Don’t discourage new developments like Woodwards – encourage them. There’s a gain of social housing, food stores, drug stores, because the developers can make that happen, and non-profits can’t — especially in the absence of provincial funding.”

“I just don’t feel that the city is listening and I don’t fully understand why,” says Geller.

Since 2007, the city and provincial government have partnered to build 14 social housing projects on city-owned land. Many of the projects have already opened, and more are scheduled to open soon, including two more projects in the Downtown Eastside: 146 units at 606 Powell Street and 139 units at 111 Princess Avenue.

In fact, the provincial government says they aren’t in the business of building purely social housing anymore, instead focusing on housing for people with mental illness and homelessness.

Wes Regan of the Hastings Crossing Business Improvement Association also has concerns with the plan, and says business owners were forgotten.

“We have felt this has largely been a housing and social planning focused plan. Businesses in many respects were unfortunately an afterthought. Now we are working with the city to play catch-up.”

However, Regan thinks concerns about the area becoming a ghetto due to a concentration of social and rental housing are overblown.

“The inclusionary zoning that they are putting in there is actually more true to the social mix philosophy that the city has had for the last several years in the area, than it is ghettoization,” he says.

He points to an upcoming social and rental housing project by Atria on the site of the current United We Can bottle depot on East Hastings Street.

“If we are taking the upcming Atira project on Hastings as an example, some of the rental units will be $1,600 a month. That won’t be low income folks renting those – it will be young professionals working nearby in the tech community. So I think the ghettoization argument is pretty weak.”

Reimer says the city has taken great steps to include local residents in the development of the plan, especially those from the low-income community.

“The Downtown Eastside has always had a high concentration of low-income people, whether there was social housing or not, because it’s always had cheap land, and therefore, cheap housing.”

She says that getting people into housing is the first step to helping to stabilize their lives and in turn, reduce some of the street disorder in the neighbourhood.

“We’ve built a plan around ‘if you house people, and provide the community services to support people in the treatment that they need for whatever issues they have, which in some cases is just being very poor and lacking housing, you can help get rid of the challenges we see on the street,” says Reimer.

But Geller says the city has given up on the core of the nieghbourhood, and caved into pressure from anti-poverty activists.

“Many of the representatives of the low-income community, especially the Carnegie Community Action Project, can be very forceful in expressing their views. After a while, it’s quite easy for the Stockholm Syndrome to take hold,” he says. “And that actually what I believe has happened to many of the planners. They have simply become overwhelmed by the needs of the low-income community and this has blinded them to the absence of economic feasibility and blinded them to the concerns that the rest of the city has about this neighbourhood.”

“The Downtown Eastside is a unique neighbourhood, in that it’s something that the whole city cares about. For that reason, I don’t think you can’t just do what the very low-income population and the poverty activists are demanding,” says Geller.

He says many of the non-profits operating in the neighbourhood have an interest in keeping things the way they are.

“Just like mining and forestry, there is a poverty industry in the Downtown Eastside. Those who are funded by it, are as keen to protect it, as others are to protect fishing and lumber. It sounds crazy, but it’s part of the problem. Of course the poverty industry cares about their clientele but it doesn’t always act in their best interests.”

Reimer says the plan reflects the wishes of the residents of the neighbourhood, as with community plans in any other neighbourhood across the city.

“If you live in a community no matter what your income is, you have every right to participate in a plan and the expectation that the community plan will provide for your future. The plan is built around securing low-income assets and tenure.”

View a PDF of the plan:

Comments