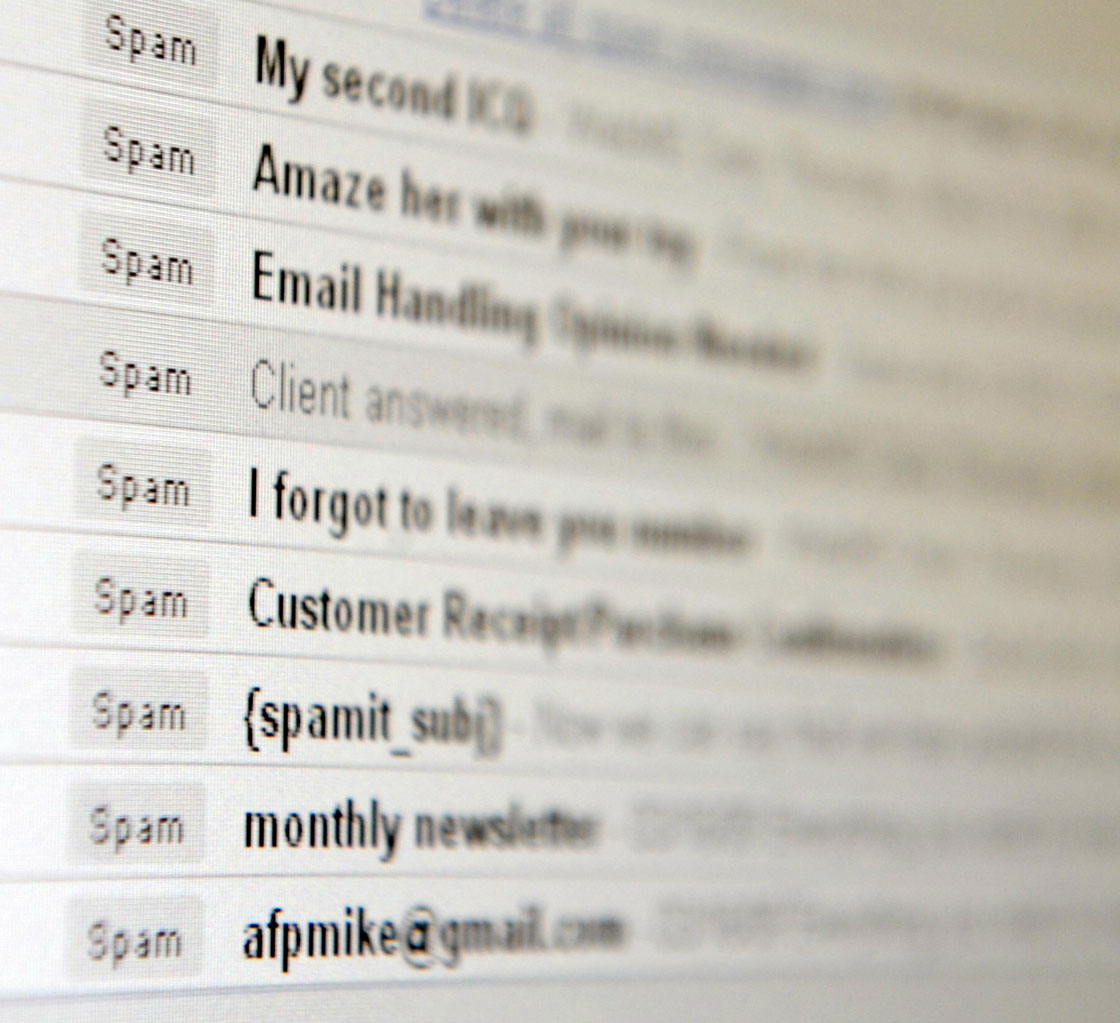

TORONTO – Canada’s anti-spam legislation was created to help Canadians regain control of their overflowing inboxes – but ironically, the law has caused a dramatic increase in spam mail.

“Please say yes,” read an email from Vancouver-based yoga retailer Lululemon, asking email subscribers to confirm that they wished to receive updates from the company.

Canadians have been receiving hundreds of emails just like this as the deadline fast approaches for businesses to obtain express consent from email subscribers in order to comply with the new federal legislation – leaving many with overflowing inboxes.

The law, which comes into effect on July 1, requires businesses to obtain explicit consent from a user in order to send them an email.

Implied consent – when a company assumes you have given consent by providing your email address when making a purchase, for example – is no longer good enough.

READ MORE: CRTC says anti-spam law will be hard to police

“It helps to explain a little bit why some people are surprised to be receiving all of these emails right now asking for full consent, wondering how did these people get my email address in the first place.”

Geist, who worked on the task force that advocated for an anti-spam law nearly a decade ago, said the process has undoubtedly caused more spam for Canadians due in part to the lack of understanding of the legislation.

“There has been so much fear-mongering associated with this legislation that some companies are doing things that frankly aren’t necessary,” he said. “Certain businesses are going beyond what’s required of the law.”

Some users have reported receiving consent emails from companies which they have already provided explicit consent to – something Geist calls a “double confirmation” tactic.

He said while this isn’t necessary under the anti-spam legislation, many businesses are doing so out of fear of violating the new law.

READ MORE: Canada’s anti-spam law coming into force next year

Under the existing law, the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA), businesses who are engaged in marketing still need to obtain consent, keep a database of that consent and respect a consumer’s right to opt out of email lists.

The new law is stricter in terms of the information businesses must include in their emails and the switch from implied to explicit consent.

Businesses that violate the new law could face financial penalties of up to $10 million per violation, while individuals could be fined up to $1 million per infraction.

“It’s not as if this is coming out of left field with the sense that there are no obligations or no requirements under the law even today – the difference in a sense is that there are real penalties,” Geist said.

Business groups cry foul over anti-spam legislation

The Canadian Chamber of Commerce, the Canadian Marketing Association, the Canadian Wireless Telecommunications Association and the Entertainment Software Association of Canada submitted a lengthy document that opposed much of the law in February.

READ MORE: Canadian business groups push back against anti-spam law

“Red tape and legislation tends to hit small businesses the hardest. When you add and create legislation without really keeping a small business owner in mind, it’s hard for policy advocates to really think about what the impact is on the ground.”

Moreau said small businesses especially will be hit with significant costs, especially if they do not have an electronic database to keep track of customer consent.

“That business owner is not really the one captured under the legislation in terms of how policy advocates were thinking about how this would be designed – they were thinking about telecom companies, for example, who can ask their chief compliance officer to help them comply,” she said.

“For a small business owner they are the owner, the chief compliance officer and sometimes their own accountant all rolled into one.”

Businesses will also have to deal with consumers ignoring consent emails, especially with so many flooding their inboxes.

But Geist noted this could have a positive effect on businesses.

“From a business perspective I do raise the question of how good was your list to begin with if people think so little of it that they aren’t willing to keep receiving your messages,” he said.

“What I think many businesses will end up with is certainly a smaller list, but probably a more effective list because it will be one of consumers that want to hear from the company.”

Moreau said the federation is urging all small businesses to obtain express consent “one more time” before July 1 to be sure they aren’t in violation – once again contributing to all of that email.

On the up side, Geist said this provides consumers with a chance to clean up their inboxes by either ignoring the consent emails or choosing to opt out altogether.

Comments