On Open Access Day, the National Archives in the Netherlands declassifies thousands of government documents that have been cleared for public access.

In 2022, files from 1947 turned 75, and reached the maximum number of years a document can be hidden from public view. On Jan. 3, they were officially made public — and one file, in particular, is attracting global attention.

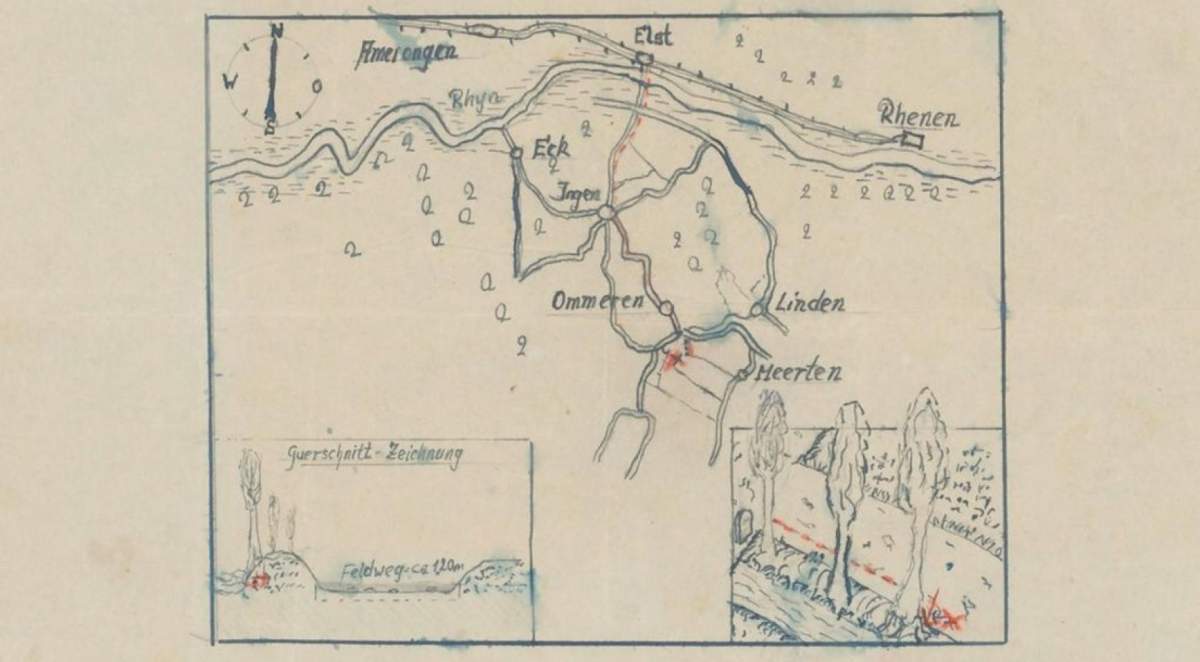

“A real treasure map this time,” the National Archives wrote in its annual press release for Open Access Day, “containing the clues to a never-found Nazi treasure that is said to be buried near Ommeren.”

The decades-old map is believed to mark four spots where German soldiers hid treasure worth millions of dollars, containing diamonds, rubies, gold, silver and all sorts of jewelry. Archivists believe that the treasure was looted from a bank in nearby Arnhem during battle and was buried shortly after.

The release of the map on Jan. 3 sparked a treasure-hunting craze in the Netherlands. Armed with metal detectors and shovels, groups wandered through the fields surrounding rural Ommeren in search of the buried gold.

According to the National Archives, researchers have looked for the treasure “several times in vain,” and some believe that the loot could have been dug up long ago, or shortly after it was buried.

- Judge orders 5-year-old Liam Conejo Ramos and his dad released from ICE detention

- Earliest launch date for Artemis II set for Feb. 8 after cold weather delay: NASA

- U.S. Senate passes funding deal as shutdown looms, DHS debate to come

- Jeffrey Epstein denied permission to visit Canada in 2018, documents show

The map for the treasure was created based on the testimony of a German soldier who allegedly witnessed some of his fellow soldiers burying boxes of gold. A Dutch institute tracing German capital in the Netherlands after the war interviewed him, and drew the map to his instruction, down to the fact that the treasure was buried next to a poplar tree, Dutch News reported.

Get breaking National news

Although the existence of the treasure could never fully be confirmed, archivists believe it to be a credible claim.

“We don’t know for sure if the treasure existed. But the institute did a lot of checks and found the story reliable,” said National Archive spokeswoman Anne-Marieke Samson.

“But they never found it and if it existed, the treasure might very well have been dug up already.”

But that hasn’t stopped people from wanting to get in on the search.

“I see groups of people with metal detectors everywhere,” 57-year-old Jan Henzen told Reuters as he took a break from his own search.

“Like a lot of people, the news about the treasure made me go look for myself. The chance of the treasure still being here after 70 years is very small I think, but I want to give it a try.”

Former Ommeren mayor Klaas Tammes, who now runs the foundation that owns the lands that might hide the treasure, said he had seen people from all over the country.

“A map with a row of three trees and a red cross marking a spot where a treasure should be hidden sparks the imagination,” he said.

“Anyone who finds anything will have to report it to us, so we’ll see. But I wouldn’t expect it to be easy.”

In fact, so many people showed up to look for the buried gold, that the nearby municipality of Buren had to issue a statement urging people to go home.

“Searching there is dangerous because of possible unexploded bombs, landmines or grenades. We therefore advise against searching for the Nazi treasure,” they said on Thursday.

The statement also noted that, under Dutch laws, would-be treasure hunters need permission to operate metal detectors and “archaeological excavations are prohibited, except for organizations with an excavation certificate.”

— With files from Reuters

Comments