KHARKIV, Ukraine — The rocket was sticking out of the ground behind an industrial building. Tipped off by local residents, workers wearing helmets and body armour arrived in a truck to remove it.

They found another rocket on the rooftop and extracted a third from the kitchen of a wrecked apartment. Fragments of another were embedded in a playground behind a daycare centre.

After more than three months of attacks by Russian forces, Ukraine’s second-largest city is beginning to clean up and restart, but the challenges are daunting and the rockets keep coming.

Although Russia appears to have given up hope of capturing Kharkiv, once the capital of Soviet-era Ukraine, its forces continue to fire at civilian neighbourhoods from positions north of the city.

Russian shelling killed nine people on Thursday, including a five-month-old baby. Another 19 were injured. The attacks seem to have no purpose beyond harassment.

Asked why Russia was shelling Kharkiv without any obvious military aim, a Ukrainian soldier had a simple theory: “Because Putin is an asshole.”

President Volodymyr Zelensky visited Kharkiv on Sunday to thank his troops. He said the more than 2,000 houses destroyed in the region would be rebuilt.

“We will restore everything,” he said.

Part of the “New Russia” imagined by some in Moscow, Kharkiv was a key target of President Vladimir Putin’s Feb. 24 invasion, but his army failed to seize the city and instead occupied surrounding villages.

Ukrainian defence forces have now pushed the Russians back towards the border, and there are more cars on the roads and people on the streets. The mayor has encouraged businesses to re-open.

But the chief of the Ukrainian battalion that has been fighting around the city said on Saturday that Russian troops still needed to be cleared from the Kharkiv region.

“I am recommending not to come back to Kharkiv yet,” Konstantyn Nemichev of the Kraken Battalion told reporters. “It’s still dangerous.”

The Russian border is only 40 kilometres from the city centre, and the frontline is closer. Twenty minutes north on the highway to the Russian city of Belgorod, the bridge over the Lozovenka River has been destroyed.

Get breaking National news

In the nearby town of Ruska Lozova, few houses remain intact and dogs own the streets. Vehicles marked with Russia’s Z logo have been abandoned outside homes.

“I was sick, that’s why I was not able to leave,” explained Helena Yehorova as she sat on a bench in the sun outside her front gate in Ruska Lozova.

An 80-year-old who spent her life working at a poultry farm, she said her apartment was damaged by a rocket but she was saved by the bathroom walls.

“I survived by a miracle,” she said.

She moved into a nearby home abandoned by its owners, who were part of her extended family. The Russian soldiers told Yehorova they had come to save the people, she said.

“And I asked, from whom are you coming to save us?”

She said there was little food in the village and she relied on humanitarian donations. The constant shelling was unbearable, she said.

“It’s totally hell,” she told reporters, who were accompanied by Ukrainian soldiers. But she was fatalistic. “I’m not afraid of anyone because I will die soon anyway.”

Despite the daily firing in and around Kharkiv, the city has been trying to move on. Mayor Ihor Terekhov stood on the platform at Central Market station last week and reopened Kharkiv’s subway system.

For three months, the metro was shut because of the war. Its underground stations became bomb shelters and camps for those whose homes were destroyed. But the mayor said it was time to restart the city’s economy.

Waiting for the next train, a commuter said the decision might have been premature but Kharkiv was a big city and needed its transit system. “It’s also a feeling of peacefulness,” he said. “It’s like the old life coming back.”

The return of the subway brought residents out into a heavily-damaged city. Rockets and missiles damaged thousands of buildings and more than 200 schools.

An official charged with patching up buildings before winter said he was working through 8,000 requests for repairs. Many have roofs damaged by shelling, particularly in the hard hit Saltivka district, said the director of the program, Bogdan Dolyna.

With attacks ongoing, two of his staff have been injured, and one was killed. “Putin should pay for it,” he said of the damage. “They destroyed it and they should pay for it.”

War crimes investigators are also assessing the damage. They visited an apartment building last week that had been bombed by a Russian plane, which was later shot down.

Twenty-six died in the March 1 attack. One of the two bombs struck outside Olga Dergach’s ground floor apartment while her grandmother was sitting at the table by the window.

The explosion drove glass shards into her grandmother’s body, who was in the hospital for a month. A nail flew into Dergach’s leg.

The building had nothing to do with the military and many residents were pensioners, she said. Witnesses have reported seeing the pilot eject.

If he is found, she wants him punished fittingly. Asked what his sentence should be, she said: “The same that happened to us.”

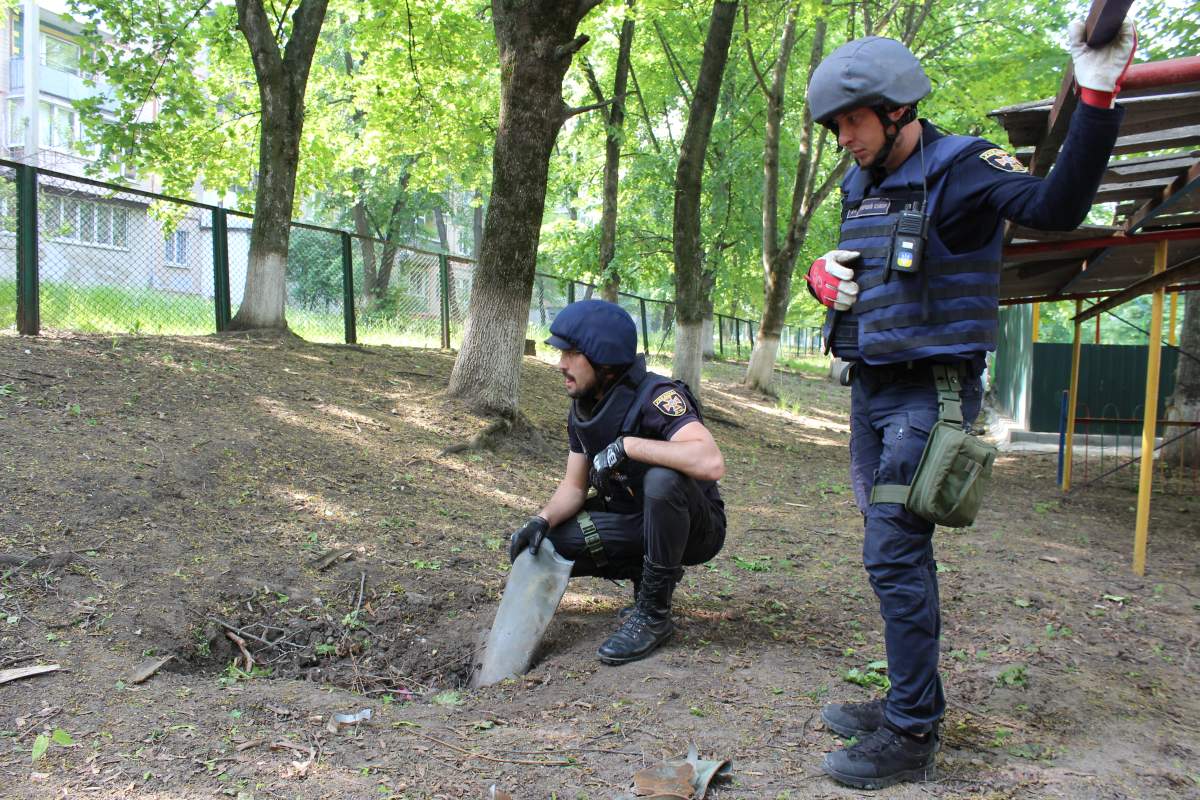

Leading the spring clean-up of Kharkiv are members of the State Emergency Service, who have been collecting Russian missiles and rockets that have landed around the city.

They mostly find Grad, Smerch and Uragan rockets, as well as mines and anti-tank missiles, said Vladimir, a member of the ordinance disposal team.

The munitions turn up in fields, riverbanks, forests, houses and rooftops. The team takes them to a collection point to be destroyed.

Vladimir said he was a father and that seeing rockets in playgrounds upset him. “I am really angry. I want to kill them with my hands, each of them,” he said.

Behind a daycare centre, he met Sergiy Abramov, who guided him to a rocket fragment he found dug into the dirt at his son’s playground.

“I understand why they destroy military objects, but I don’t understand why they target a kindergarten,” Abramov said.

He showed reporters his apartment building, which had also been bombed. The windows were gone and the exterior was charred black.

His wife Ilona said she had lived in the neighbourhood all her life and watched its decline since Russia’s invasion.

The market was destroyed, the buildings were destroyed. It’s like an empty village, she said. More than 200 schools are damaged.

It was too hard to explain to her son Igor. He was only three and couldn’t understand. When he’s older they will tell him, she said.

She didn’t flinch at the sound of another explosion.

“It’s calm,” she said.

stewart.Bell@globalnews.ca

Comments