Catastrophic and extreme weather events have wreaked havoc in British Columbia this year.

Within a matter of about four months, the province has gone from experiencing a record-setting heat wave with raging wildfires to heavy flooding, which has forced mass evacuations.

The dramatic shift in the weather system is unprecedented for Canada, experts say.

“It’s extremely unusual,” said Anthony Farnell, Global News’s chief meteorologist.

“I don’t remember ever seeing this in Canada, where you have those two extremes, from dry heat and then the fires and then over the same exact areas this record amount of rainfall.”

From severe drought that kicked in at the end of June to the province’s latest atmospheric river, B.C. has undergone a “drastic change,” said Armel Castellan, a warning preparedness meteorologist at Environment and Climate Change Canada.

“This summer was extremely dry and warm, and we flipped that switch about the 14th of September … when things started to get very wet and without really much of a relent.”

Here’s how it has played out.

A “heat dome,” which is a high-pressure system that traps warm air underneath it, raised the mercury to unprecedented levels, hitting the mid-40s in late June and shattering dozens of heat records across British Columbia.

On June 29, the small town of Lytton set a new national high of 49.6 C, breaking records over three consecutive days.

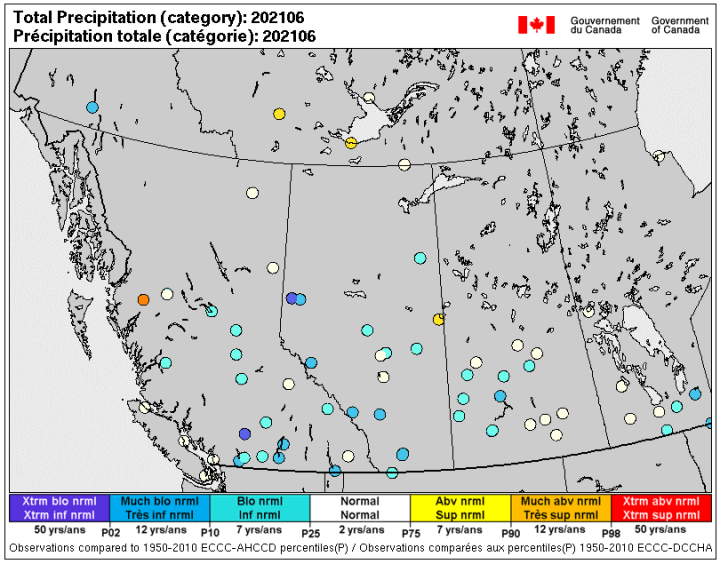

On top of the anomalous day and night temperatures, there was lack of rain from mid-June until at least early to mid-August for southern B.C. , said Castellan.

Get breaking National news

Amid the extreme drought, most places only saw minimal rain of a millimeter or two for weeks, said Farnell.

As hundreds of wildfires raged and forced mass evacuations, the province declared a state of emergency that went into effect on July 20.

This year, a total of 1,634 wildfires have been recorded in B.C. that burned 869,209 hectares of land, as of Nov. 15. This was a significant increase compared to a year before when 670 fires were recorded and 14,536 hectares were burned.

In mid-August, heat warnings were in effect for 100 Mile House, Central and North Coast, east and inland Vancouver Island, Fraser Canyon, Fraser Valley, Greater Victoria, Howe Sound, Whistler, Metro Vancouver, North and South Thompson, the Sunshine Coast and the Southern Gulf Islands.

Daytime highs ranged from 35 to 38 C, combined with overnight lows of 17 to 20 C.

After weeks of scorching heat and drought, there was some reprieve in August as northern B.C. experienced short-term rain. That helped shrink the fires in geography while still remaining intense, said Castellan.

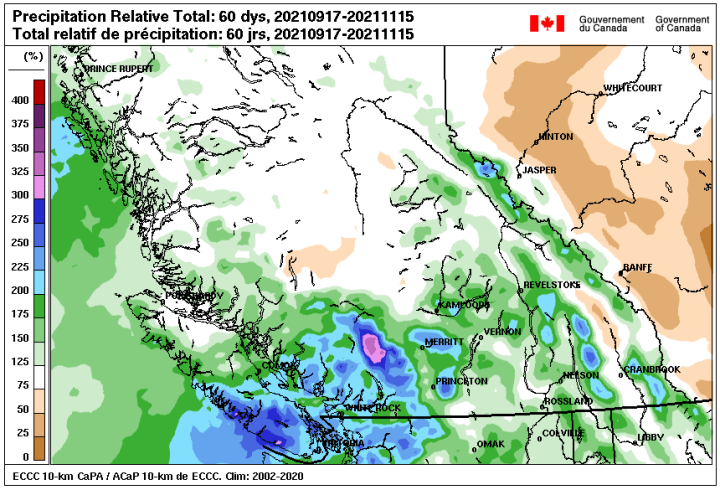

However, the tide significantly turned in mid-September when the typhoon season spurred into action in the western Pacific Ocean. Since then it has been eight to 10 weeks of torrential rain.

In September, many areas saw precipitation in excess of 300 per cent of normal, according to Castellan and in October, the excess ranged between 200 and 240 per cent of normal along the south coast.

In mid-October, Environment Canada issued a special weather statement covering Metro Vancouver, the Fraser Valley, Howe Sound and Whistler, the Sunshine Coast and eastern, western and inland Vancouver Island.

Environment Canada said a pair of frontal systems were expected to arrive packed with moisture “associated with an atmospheric river flowing from the southwest off the Pacific Ocean.”

That has led to what we’re looking at now across much of B.C.

The District of Hope saw its wettest day on record on Sunday, with rainfall adding up to 174 millimetres, Castellan said.

The City of Chilliwack also reportedly broke records on Sunday, with rainfall of 154.6 millimetres.

“It is a little bit mind boggling. We’re going to likely be analyzing these numbers for days and weeks to come because they are that extraordinary,” said Castellan.

Flooding has forced the evacuation of the entire community of Merritt, B.C.

An evacuation order has also been issued for the entire portion of the Sumas Prairie to the Chilliwack border in the eastern Fraser Valley.

The City of Abbotsford declared a local state of emergency on Tuesday, and asked residents to leave immediately as water levels rose rapidly.

Going forward, there will be some reprieve for the province, with some showers and flurries in the mountains.

“For the next week to maybe even 10 days, there will still be some rain from time to time, but no flooding, no significant systems that I see,” said Farnell.

However that may change towards the end of November going into December as the La Nina winter kicks into action, he added.

“It’s tough to say that there’ll be any more extremes like we’ve seen, but definitely above normal rainfall is on the way for coastal areas this coming winter.”

What is behind the dramatic shift?

Climate change is a contributing factor for the extreme weather events and B.C., with its mountainous terrain and geographical location has become a poster for it, said Farnell.

“These events are happening more frequently and climate change is one of the reasons for that,” he added.

However, Castellan said what we’re seeing now is very much consistent with wet climate projections from decades ago.

Burn scars left by the wildfire season, and melting snow on the mountains that wasn’t thick enough to survive the rain have also played a role in the atmospheric river’s intensity and impact on the ground, Castellan said.

— with files from Global News’ Elizabeth McSheffrey, Kristi Gordon

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.