After a prolonged battle with the provincial government, an Ontario First Nation has finally obtained critical air pollution data — previously held in secret — showing alarming levels of a cancer-causing chemical in the air.

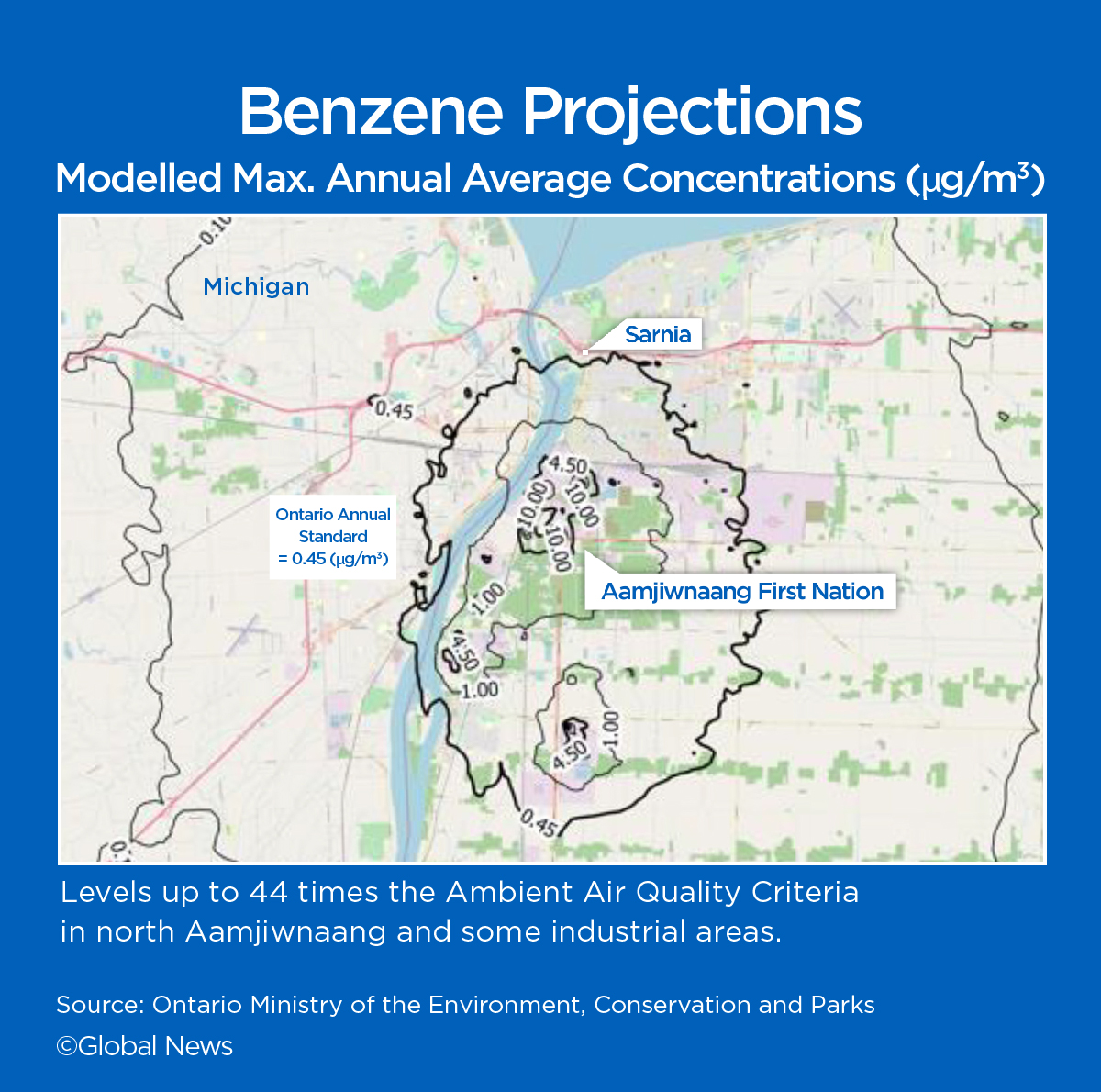

Newly revealed data from the Ministry of Environment, disclosed last week following questions from Global News, shows a startling forecast for benzene pollution, a chemical linked to cancer, up to 44 times the annual level in the northern part of the First Nation.

Members of Aamjiwnaang First Nation, located along the Michigan border, said the Ontario government has been stonewalling them and withholding crucial data for years in what amounts to a “disrespectful” partnership that has treated them as less than equal.

“When we’re talking with the ministry and the province about nation to nation and reconciliation, if we can’t even get a minister to answer our letters, it speaks to the commitment of the government,” said Aamjiwnaang’s environment coordinator Sharilyn Johnston.

Aamjiwnaang had been asking the government for the benzene data for months, and for other air pollution reports since 2017. Community members were also anxiously awaiting a new government regulation to reduce sulphur dioxide (SO2) emissions from nearby petroleum plants.

Both the reports and the proposed SO2 regulation were released last week following questions from Global News.

“The only reason that he shared any of the data is because of the pressing by (Global News),” said Aamjiwnaang Chief Chris Plain.

Health concerns in Chemical Valley go back years

Aamjiwnaang First Nation lies on the south side of Sarnia and is surrounded by heavy industry.

The area is known as Chemical Valley: a cluster of more than 50 registered polluters — some located mere steps from the homes in Aamjiwnaang.

For years, the people living here have suspected the high level of pollution was making them sick. A study published last spring by an Ontario health research institute indicated that air pollution is likely contributing to a higher risk of asthma in kids in the region.

Other serious health concerns — including cancer cases — have remained anecdotal in the absence of hard data.

A 2017 Global News investigation, in partnership with the Toronto Star and the Institute for Investigative Journalism, exposed a pattern of industrial leaks and spills in the Sarnia area and revealed the stories of residents who believed it was making them sick.

Just two days after the investigation was made public, the provincial government announced it would launch a health study that the community had been requesting for a decade.

The stakes of the health study are high.

Get breaking National news

Should it prove a connection between elevated air pollution levels and adverse health impacts, oil and chemical companies — the lifeblood of Sarnia — could be forced to invest millions to renovate their plants.

The financial cost, some speculate, could jeopardize Ontario’s competitive advantage, putting jobs at risk.

A spokesperson for the Environment Ministry said the Sarnia Area Environmental Health Project will “enhance our understanding of the links between environment and health.” It is slated to be completed this spring.

The people of Aamjiwnaang were eager to see the underlying data.

In 2017, the provincial government, then led by Kathleen Wynne, assured the Aamjiwnaang First Nation that it would be included in the project, which the government said would “improve the relationship with Ontario’s Indigenous communities.”

The Ford government also reiterated its importance.

“People can count on us to make sure that the health study gets done, obviously in partnership with the Aamjiwnaang First Nation, with the town, with the health authorities,” former environment minister Rod Phillips said in 2018.

While the Ministry of the Environment has kept the First Nation regularly updated on the project, until last week it withheld key air pollution data informing the health study.

“This is just the continuation of the Canadian legacy of putting Indigenous people, people of colour, at a lower place,” said Janelle Nahmabin, chair of Aamjiwnaang’s environment committee, who goes by the spirit name Red Cloud Woman.

The recently released benzene data is part of the health study’s air exposure review, which is meant to identify the hazards, evaluate exposures and characterize risks.

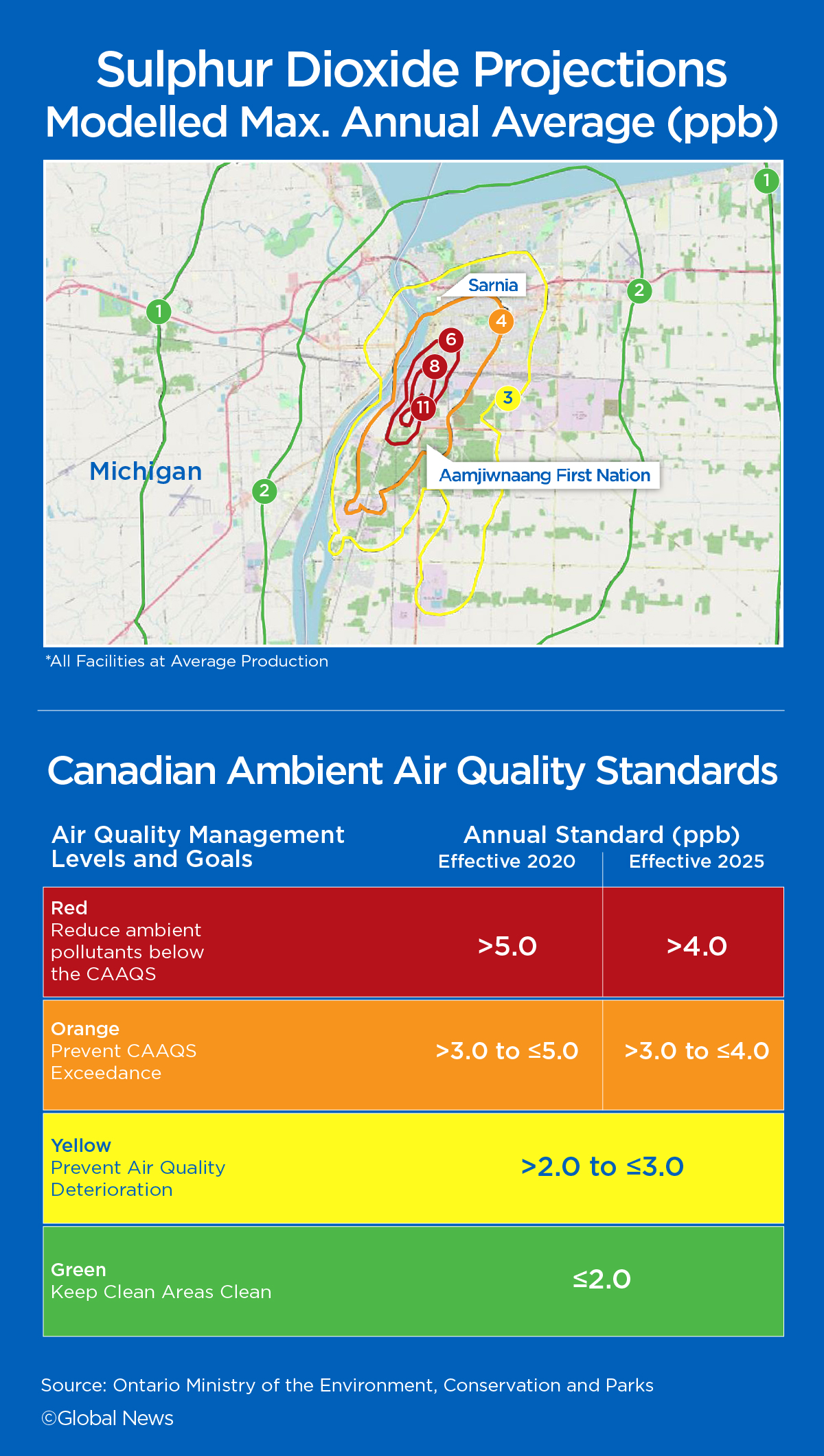

Five priority chemicals were identified by the ministry for inclusion: benzene and 1,3 butadiene, which are known carcinogens, as well as sulphur dioxide, which can cause respiratory distress.

All five chemicals were modelled by the Ministry of the Environment — a projection of pollution levels based on combined industrial emissions and weather patterns.

Global News was able to obtain part of that modelling data, under freedom of information legislation. The data indicated sulphur dioxide levels at much higher concentrations than most Canadian cities.

The maximum annual average of sulphur dioxide over three years was forecast to be as high as 11 parts per billion (ppb) in Sarnia’s industrial heart and five to six ppb in north Aamjiwnaang, which is located close to a petroleum plant.

Toronto, by contrast, had an annual SO2 level of 0.3 ppb for the last year data was reported.

The Canadian Ambient Air Quality Standard for SO2, a non-enforceable standard, is five ppb annually, and is being lowered to four ppb annually in 2025.

“These are very high levels,” said Scott Grant, an air pollution engineer who retired from the Ontario Ministry of the Environment and is now consulting with Aamjiwnaang.

“There have been a number of studies going back into the early 2000s that demonstrate an increased level of hospitalizations and increased level of mortality, even with these higher levels of SO2 on a long-term basis. This is a significant concern.”

On Oct. 27, Global News contacted the Ministry of the Environment seeking information about sulphur dioxide and its health effects. On Nov. 1, there was a follow-up request for more data and an interview with the minister — which was not granted.

On Nov. 9, however, the ministry proposed a new regulation for sulphur dioxide.

If it is approved, heavy emitters would be required to reduce SO2 levels by 30 per cent by early 2022 and would have to reduce emissions by up to 90 per cent by the end of 2026. It would also allow the province to fine a company up to $100,000 for contravening the new requirements.

“Our facilities in Ontario, near Aamjiwnaang, are decades behind in terms of air pollution control,” Grant said.

“There are cost-effective solutions that have already been proven in the United States that could be applied here.”

The proposed regulation also stipulates that companies will have to share emissions data with local municipalities and First Nations.

‘Tired of empty words’

Among the other documents disclosed to the First Nation this week: an air monitoring report that shows the government had been aware of how severe the benzene levels were for years.

The emissions report was published in 2017 by a Swedish firm hired by the ministry to conduct specialized air monitoring using “state of the art” infrared and laser techniques.

It measured the air quality at 18 different locations in the Sarnia area and found benzene levels outside two of the industrial plants which neighbour Aamjiwnaang up to 10 times Ontario’s hourly benchmark. The report also zeroed in on the specific sources of the emissions.

Aamjiwnaang had been asking the government for this report for four years.

“It is unconscionable as to why the Ministry would fail to produce a report to Aamjiwnaang First Nation,” Aamjiwnaang Chief Chris Plain wrote to Environment Minister David Piccini on July 13, 2021.

Currently, benzene emissions have been reduced in parts of Aamjiwnaang, but they are still well above Ontario’s stringent air quality standard.

An independent analysis by Global News found the annual benzene level in 2020 at a government air monitor on the north side of Aamjiwnaang was still seven times Ontario’s Ambient Air Quality Criteria — a threshold established to protect health.

Environment Ministry spokesperson Gary Wheeler said that level is a 50 per cent reduction from 2019 and the government has taken action by issuing orders, requiring an industrial plant across from Aamjiwnaang to reduce its benzene emissions.

For Red Cloud Woman of Aamjiwnaang, the continued pollution and the lack of partnership is environmental racism.

In an era of reconciliation with Indigenous communities across Canada, she said the rhetoric of rebuilding relations rings hollow.

“We’re tired of empty words. We want action.”

Comments