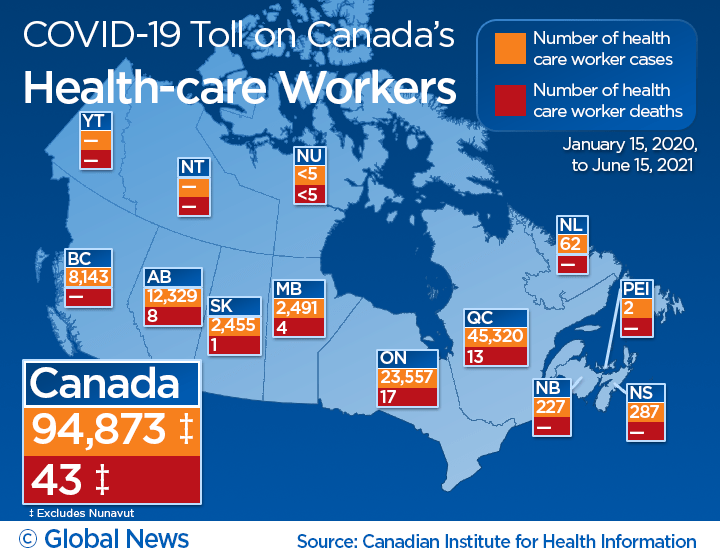

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to take a toll on Canada’s health-care workers, with nearly 95,000 cases and 43 deaths reported since the start of the pandemic.

The latest figures, as of June 15, 2021, were released by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) on Thursday.

Data collected by CIHI showed a 43 per cent jump in cases among health-care staff across the country since January. But the share of cases out of Canada’s total tally among the general population has continued to decline — reaching roughly seven per cent — amid greater vaccination coverage, CIHI reported.

“It’s been a significant impact on health-care workers who provide care to Canadians and we’re seeing that in a number of aspects, including the total COVID-19 cases and deaths that have been experienced,” said Lynn McNeely, manager of health workforce information at CIHI.

Beside the physical impact, McNeely said the pandemic has also presented mental health challenges for health-care workers grappling with long hours and COVID-19 fatigue.

“There’s no doubt health-care workers have been working tirelessly for the past year and a half under some really challenging conditions,” she told Global News.

Personal support workers (PSWs) were at the greatest risk of contracting the disease compared with physicians and nurses, data from Ontario, Manitoba and British Columbia showed.

Because PSWs tend to work on a part-time basis at multiple facilities, that puts them at an increased risk of exposure, McNeely said.

Get weekly health news

Of all the provinces, Quebec was the hardest hit, reporting 45,320 cases and 13 deaths among the health-care workers. Ontario, Canada’s most populous province, came in second place with 23,557 infections and 17 deaths.

With the country in the midst of a fourth wave of COVID-19 fuelled by the highly transmissible Delta variant, there is a greater push to make vaccinations mandatory for health-care workers.

In Quebec, health-care workers will be required to be fully vaccinated against COVID-19 by Oct. 1, Premier Francois Legault said Tuesday.

The Ontario government will also be requiring hospitals and home and community care service providers in the province to enact COVID-19 vaccine policies by Sept. 7. Individuals will need to provide proof of full COVID-19 vaccination, a medical reason for not having COVID-19 vaccines, or they will need to complete a COVID-19 vaccine educational session, the province said in a statement.

Meanwhile, on Aug. 12, British Columbia became the first province to order people working in long-term care and assisted living to get fully vaccinated as a condition of employment.

Staffing concerns

While the COVID-19 pandemic saw an increase in the overall supply of selected health-care professionals last year, staffing shortages remain a major concern for provinces — prompting hospitals to postpone surgeries, close emergency beds and offer incentives.

Nurse practitioners made the biggest gains with a roughly eight per cent increase followed by physiotherapists and licensed practical nurses, the CIHI report showed.

Nearly 6,000 nurses, occupational therapists, physiotherapists and pharmacists re-entered the workforce to provide COVID-19 support across the country.

“Canada’s supply of health-care workers increased as a result of workers who returned to help respond to the pandemic, as well as new entrants to the professions,” CIHI said in its report.

“Despite the increase in supply and the ability to call on those not working in profession-specific roles, health-care worker infections and exposure to the virus contributed to shortages.”

With increasing pressure on the country’s health-care system and backlog created by the pandemic, McNeely stressed the need to provide mental health support to the staff.

According to a Statistics Canada survey released in February 2021, 77 per cent of health-care workers who worked in direct contact with confirmed or suspected cases of COVID-19 reported worsening mental health compared with before the pandemic.

It’s an area that will need attention in the months and years ahead, said McNeely.

“We’re going to have to continue to monitor and closely watch that burnout, as well as staff shortages among those who have been dealing with — not only through work, but through their own personal lives — the impact of the pandemic.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.