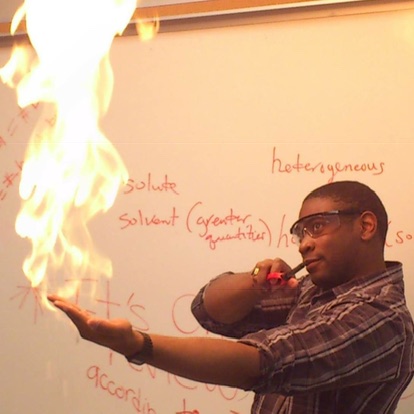

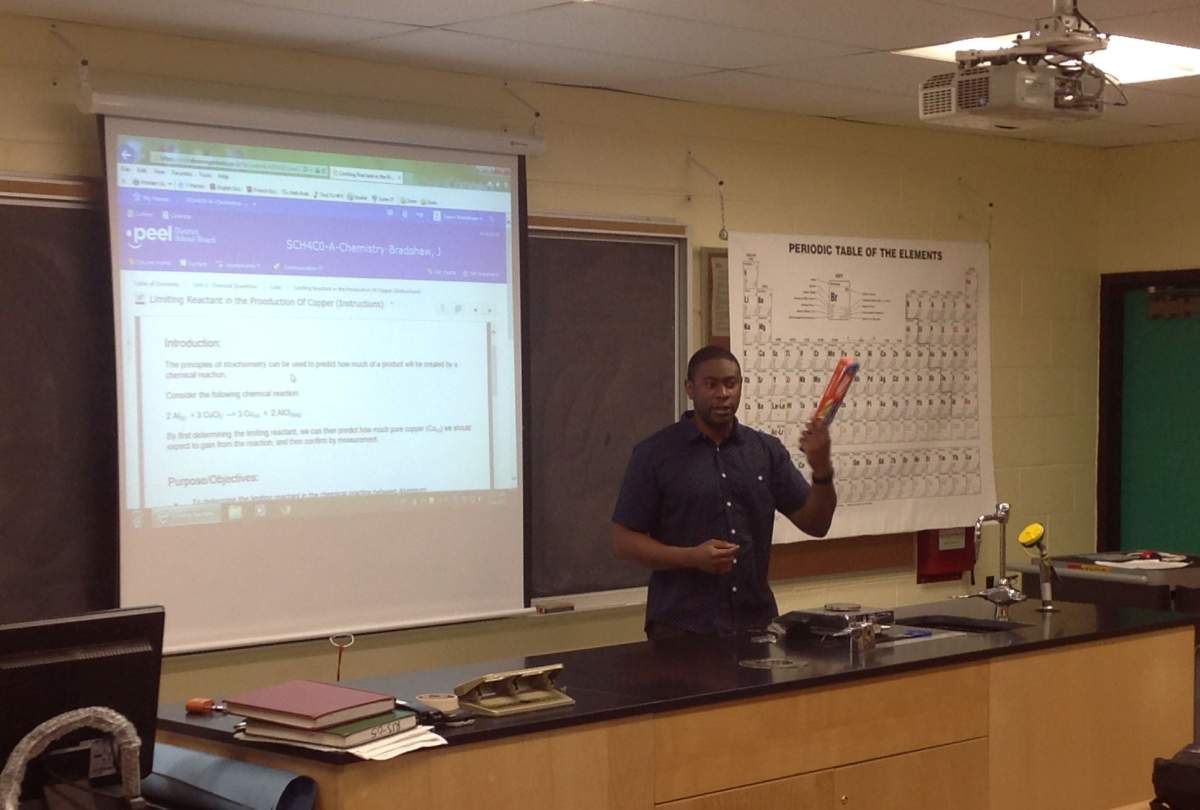

Jason Bradshaw loves teaching science, but since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s gotten harder.

“Some days when you’re when you’re just teaching online, you get out of bed and it’s like you don’t feel like you’re really teaching. You feel like you’re you’re talking to a computer screen,” the Brampton, Ont. teacher said.

“And after several weeks of doing that, I think it really does start to get to you.”

And although his high school students were able to adapt, “you can tell it’s difficult for them,” he said.

“They’re teenagers. They want to be with their friends. They want to be engaging in extracurriculars. They don’t want to be just sitting at home on a screen all day. So it was definitely challenging for them. And many of them told me as much.”

But while endless Zoom classes and uncertainty have taken a toll on Bradshaw’s mental health and that of his students, new research suggests that it’s likely not permanent.

Lara Aknin, a distinguished associate professor of psychology at Simon Fraser University in B.C., has been studying mental health during the pandemic as chair of the Mental Health and Wellbeing Task Force for the Lancet medical journal. What she and her co-authors found was that while mental health certainly suffered at the beginning of the pandemic, people seemed to have gone back to normal by the summer of 2020.

Get weekly health news

“It was a surprise,” she said. “I think a lot of us were assuming the general narrative that there had been large scale, widespread, ubiquitous, long-lasting distress.”

Looking at multiple international mental health surveys that covered hundreds of thousands of people, the researchers found that on average, people seemed to have recovered from an initial slump in mental health.

“I think the evidence is quite clear that there was significant distress early on average levels of anxiety, depression, distress had had indeed risen,” Aknin said. “But I think the evidence coming from multiple high quality data sources suggests that by and large, average levels did reduce in some cases to near baseline levels last summer, which was striking and surprising to us.”

Other mental health data over the course of the pandemic has been a bit of a mixed bag, particularly in Canada.

Some other Canadian survey data showed people reporting poorer mental health as Canada entered the second wave of the pandemic. Provinces across Canada also showed a huge increase in deaths due to opioid overdose in 2020.

However, deaths by suicide didn’t rise during the pandemic and in some cases actually fell below normal levels, according to some Canadian and international studies.

While the Lancet group’s research looked mostly at averages, it’s likely that some people fared much better or worse than others, said Luana Marques, an associate professor of psychology at Harvard Medical School.

“Before the pandemic, we already had a mental health crisis with a lot of people needing help,” she said.

“So we have a good group of people that are doing well. But then we have a group that is struggling,” she said. Some of those people are dealing with pre-existing mental illness, some are struggling with poverty, and some are from diverse and historically underserved groups, she said, and she expects that their responses to a survey wouldn’t match the rest. “I think the data there, it looks very different.”

“These large scale averages do gloss over some very important individual differences,” Aknin said. “I certainly don’t want this evidence to suggest that the real and significant and really meaningful struggles for some people did not occur. They did.”

Overall, however, Aknin thinks that the evidence points to a “widespread resilience” among people.

“Natural disasters perhaps do not need to be followed by psychological ones. We as human beings have the capacity and the ability to adapt and so we can take care of ourselves and take care of our communities,” she said.

Marques agrees.

“Psychologists suggest that all of us have a psychological immune system, which really means our ability to manage and deal with difficult things,” she said. “And when faced with adversity like this pandemic, a lot of people are able to sort of adjust and some even thrive. And that’s really what we call our psychological immune system.”

She would like to see researchers to continue to collect data, to see whether there are lasting effects from the pandemic years down the road.

Bradshaw is looking forward to a more normal classroom experience in the fall, and thinks his students will be ready for it.

“I definitely think they will be able to bounce back. And as for teachers, I think we’re also a pretty resilient group. We’re used to having to adapt on the fly.”

Comments