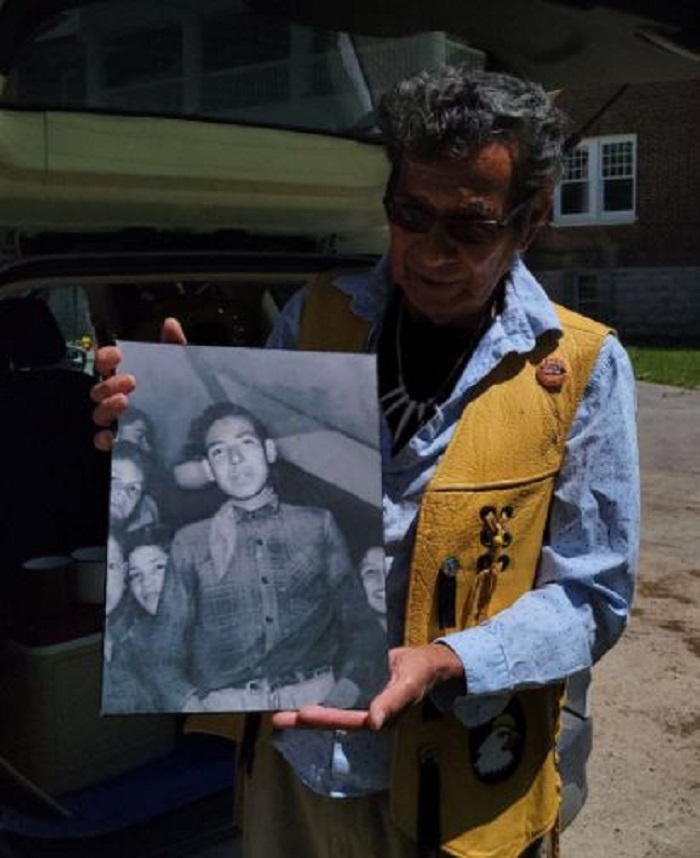

On the top of Geronimo Henry’s right hand is a tattoo that reads “M – R – S – Survivor #48” representing the words: “Mohawk Residential School Survivor” and the number Henry would be called instead of his name: number 48.

“If I ever meet the prime minister, shake his hand … that was the whole idea in the beginning and he would see that,” Henry told Global News.

The front steps of the former Mohawk Institute Residential School in Brantford, Ont., now called the Woodland Cultural Centre, have become a memorial after the remains of 215 children were uncovered at another former residential school in Kamloops, B.C.

On this day, Henry is organizing the dozens of pairs of shoes, teddy bears and flowers that continue to be left and he is calling on the government to fund a search for the remains of children he believes could be buried on the Brantford, Ont., property.

“I want them to dig at every residential school,” Henry said.

On Tuesday, the Ontario government announced $10 million will be spent over the next three years to help identify and commemorate unmarked burial sites at former residential schools.

An estimated 150,000 First Nation, Inuit and Metis children were taken from their families – forced to attend residential schools. The Mohawk Institute Residential School is one of only a few residential school buildings left standing in Canada.

Get breaking National news

The Six Nations of the Grand River community voted to keep the structure as a physical reminder of the assimilation imposed upon Indigenous children in Canada.

More than 130 residential schools operated in Canada between 1828 and 1996.

“Came out like a dysfunctional person. Just kind of like ruined my life,” Henry said.

READ MORE: Trudeau vows ‘concrete action’ after discovery of 215 bodies at former residential school site

Henry said he arrived at the Mohawk Institute when he was six years old. He recalled his two sisters leaving after around a year or so. His brother ran away after around five years but Henry said he ended up spending eleven years of his childhood at the school.

Henry said once he and his siblings arrived, school staff cut their hair off.

“They took my language, culture and ceremonies away from me.”

The Mohawk Institute Indian Residential School operated in Brantford, Ont., from 1828 to 1970. It served as a boarding school for First Nations children from Six Nations, as well as other communities throughout Ontario and Quebec.

“By the 1940s, enrollment was at 185 students,” said Janis Monture, executive director at the Woodland Cultural Centre.

“So, you can already imagine — it was overcrowded and there were already a lot of reports about the child neglect, about the children being hungry, cold in the winter, hot in the summer, reports they weren’t getting an education anymore. It was really child labour,”

Many survivors, including Henry, reported being fed oatmeal daily while the headmaster and teachers enjoyed bacon and eggs for breakfast and roast beef dinners. The regular servings of oatmeal gave rise to the children referring to the school as the Mush Hole.

After closing in 1970, the school reopened in 1972 as the Woodland Cultural Centre, a non-profit organization that serves to preserve and promote First Nations culture and heritage.

READ MORE: Calls grow for federal government to review settlement decisions for residential school survivors

“We’re doing the exact opposite of what these schools were meant to do. We’re doing language preservation, we’re doing revitalization of cultural heritage, we are telling the history from our perspective,” Monture said.

Currently 84 years old, Henry said the residential school still has a profound effect on him and his children.

“Eleven years I was here, like, nobody said they love me. When you’re small and your mom always says, ‘I love you’ and stuff and no hugs, nobody came and hugged me,” he added.

- Man guilty of 1st-degree murder for shooting of rap artist outside Scotiabank Arena

- Blue Jays legend Joe Carter to be honoured with statue outside Rogers Centre

- Ontario taxpayers stuck with nearly $100K bill for rescue of 58 dogs

- 7 suspects charged in 2024 home invasion that killed Ontario homeowner

Comments