Blacklegged ticks are slowly spreading across Canada, and they bring with them more than just Lyme disease: they can also spread babesiosis, a malaria-like illness that attacks red blood cells, and anaplasmosis, a bacterial infection.

Both illnesses, which people catch from being bitten by a tick, can cause similar symptoms: fever, chills, muscle aches and fatigue, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Many people might not show symptoms at all, but both illnesses can cause death in rare cases.

Symptoms

People with compromised immune systems or those who have suffered injuries to the spleen are much more at risk of developing a severe case of babesiosis, according to Dr. Peter Krause, a senior research scientist at the Yale School of Public Health, who has researched the disease extensively.

“People who don’t have a spleen, people with cancer, people who have HIV/AIDS, and also the extremes of age — newborn infants and people over the age of 60 — tend to have more severe disease,” he said.

Similarly, people with compromised immune systems and the elderly are at increased risk of severe disease from anaplasmosis, according to the CDC.

Both diseases are usually successfully treated with antibiotics. If caught early, Lyme disease is also easily treated with antibiotics, but effective treatment becomes more complex the longer it goes undiagnosed.

Moving north

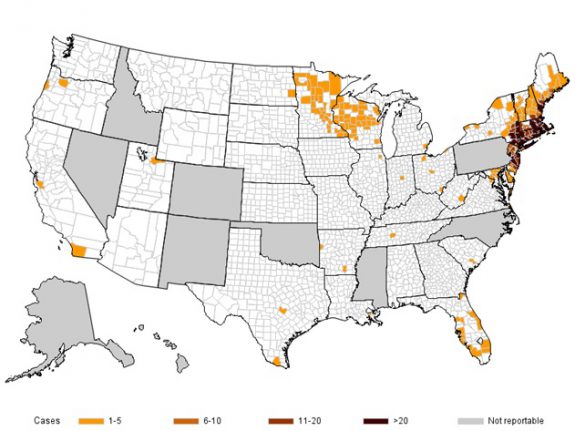

Babesiosis is currently very rare in Canada. The first locally acquired case was only reported in 2013, in Manitoba. But, cases are increasing south of the border. According to the CDC, there were 1,126 U.S. cases in 2011, and 2,161 in 2018.

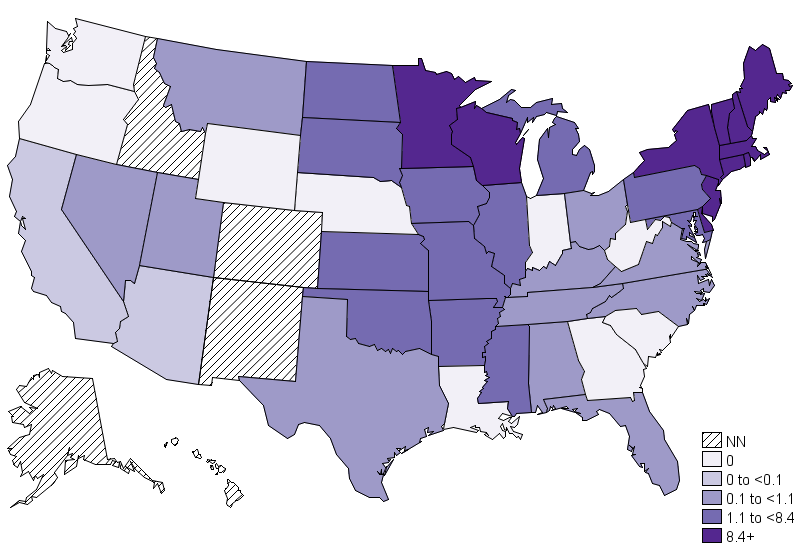

Anaplasmosis is following a similar upward trend – from 351 U.S. cases in 2001 to 4,008 in 2018, according to CDC data. While still relatively rare in Canada, human anaplasmosis cases have been found in every province that has blacklegged ticks to spread the bacterium, according to the Public Health Agency of Canada.

It’s only a matter of time before we see more cases of both in Canada, according to Justin Wood, a tick researcher in southern Ontario who runs the tick-checking website geneticks.ca.

Get weekly health news

Wood has a personal connection to ticks: he was diagnosed with Lyme disease in 2015, after suffering symptoms for some time. Lyme severely affected his life, he said.

“I used to be really active,” he said. When he caught Lyme disease, “I couldn’t participate in sports. I couldn’t really read, use a computer or listen to music. It kind of took my whole life from me.”

After getting treatment, Wood said he wanted to help others with tick-borne illness, so he started a business where people would send him ticks and he would test them for common pathogens.

And while Lyme remains the most common tick-related disease in Canada, he’s seeing more and more ticks carrying the parasites that cause babesiosis and anaplasmosis.

“Anaplasmosis and babesiosis, they’ve been in Canada for a while, but the prevalence is definitely increasing,” Wood said. “So we’ve started to see more and more of them.”

Last year, between one and five per cent of blacklegged ticks submitted had anaplasmosis or babesiosis, he said.

In Manitoba, where doctors are required to report anaplasmosis, there were 51 cases from 2015-18.

According to Robbin Lindsay, a research scientist at Canada’s National Microbiology Lab in Winnipeg, ticks with babesiosis are fairly rare – but are also much more likely in Manitoba.

“There’s something going on here in Manitoba,” he said.

Depending on where you are in the province, around one to five per cent of blacklegged ticks will be carrying a parasite that causes babesiosis, he said. More than five per cent will carry a parasite that causes anaplasmosis, according to a 2018 report from the Manitoba government.

Lindsay says that Lyme remains the most concerning tick-borne disease in Canada, but below that he would put anaplasmosis, followed by babesiosis.

The Public Health Agency of Canada plans to designate both diseases as nationally notifiable diseases, which will make their spread and prevalence easier to track, he said. Currently, while a few cases of both have been noted in Canada, the numbers are unreliable because doctors are not required to report every case.

Krause, the Yale researcher, thinks that ticks that spread babesiosis are likely to become more common in Canada, based on what has happened in the northern U.S., though its range moves more slowly than Lyme disease.

“It does seem like it’s moving north,” he said. “Global warming is also increasing, improving the habitat for ticks in Canada. And I think the expectation is that it’s going to continue to move northward.”

Protecting yourself from ticks

Protecting yourself from anaplasmosis and babesiosis is the same as protecting yourself from any tick-borne illness, Krause said.

This means taking measures like avoiding tall grass and bushy areas where ticks like to live, wearing long pants and shirts and tucking your pant legs into your socks, wearing insect repellent containing DEET or icaridin, and carefully checking yourself for ticks when you get home.

Ticks vary in size but can be as tiny as a poppy seed, so PHAC recommends feeling carefully for small bumps and looking for little dark spots on your skin. If you do find a tick, you can carefully remove it with tweezers.

Babesiosis remains a very rare infection, Krause emphasized.

“I would not lose sleep, if I were Canadian,” he said. “On the other hand, if I was immunocompromised, I would pay a little attention to this.”

–With files from Jamie Mauracher, Global News

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.