HALIFAX – Black holes, the astronomical mysteries at the centre of physics and astronomy, aren’t the cosmic vacuums people think they are.

Their activity is a lot more complicated than that, says Luigi Gallo, professor in the astronomy and physics department at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax.

“A lot of black holes actually eject a lot of material out into space,” Gallo said in an interview Tuesday.

“This material can then get shot across the galaxy, even into the space between galaxies, and it can kind of affect how galaxies form and how the galaxy evolves sometimes.”

Gallo’s research focuses on supermassive black holes – the regions in space where gravity is so strong that not even light can escape. Supermassive black holes are orders of magnitude larger than our sun.

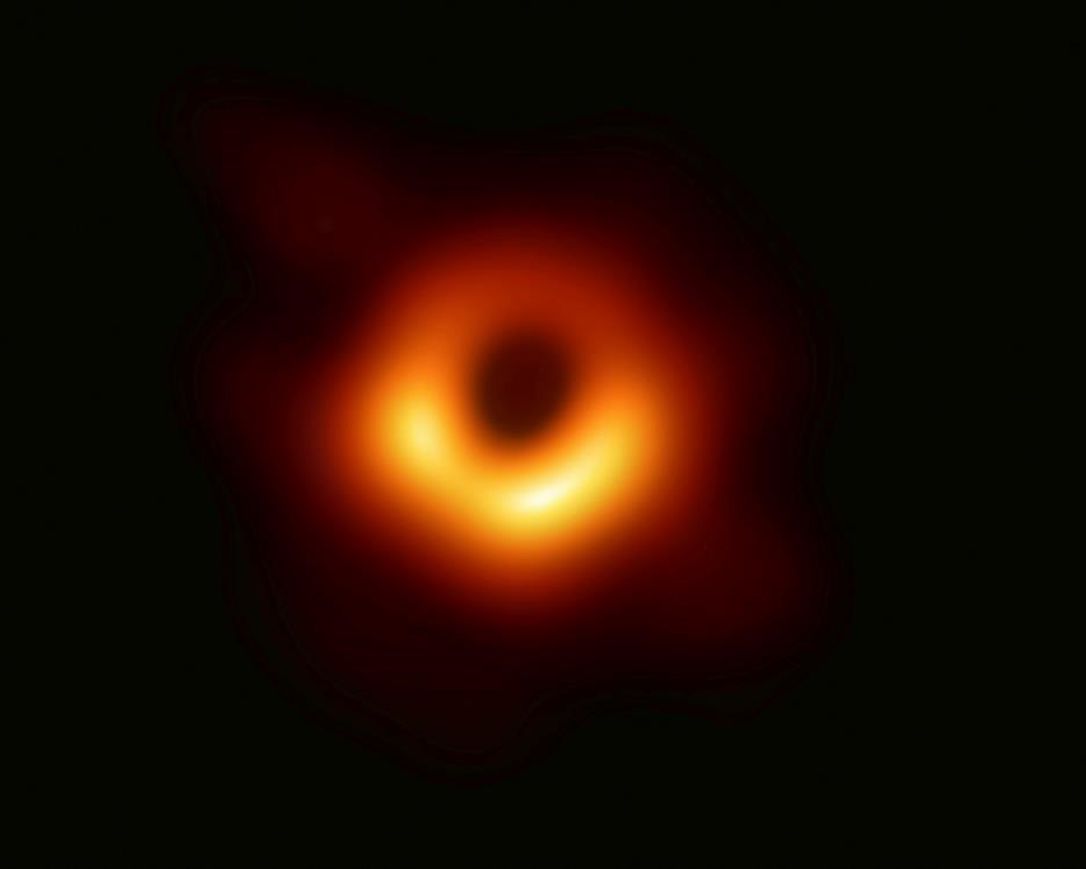

He and his students are looking into the area right at the edge of supermassive black holes as well as the high-temperature X-rays that are found there. Beyond that edge – known as the event horizon – scientists aren’t able to see what’s going on because light gets sucked into the black hole’s maw and disappears.

Gallo said by looking at the edges of supermassive black holes – the largest kinds of black holes – he and other scientists are hoping to get a better picture of the shape of the area surrounding the perimeter of those massive voids. They want to know what that area is made of and how it’s falling into the hole.

X-rays, Gallo said, are made of light the human eye can’t see. And therefore, he said, to study them, scientists are planning to launch a new satellite into space. His research is being used in the development of the satellite, called XRISM. The project is backed by NASA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, and it is set to be launched into space in 2022.

The satellite will be equipped with a tool called a calorimeter, which is a sensitive prism that will break the X-rays into a band of colours. From there, researchers will be able to use the different colours to identify the composition of the material and its movement around a black hole, giving them more information about the “geometry” of the region just outside the hole itself, Gallo said.

Get daily National news

There is an exchange between the black hole and the outer reaches of the galaxy it’s located in, Gallo said, a sort of “feedback” loop that allows the two to “know” about each other. “We understand that there’s a relationship between how galaxies grow and how black holes at the centre grow, but we don’t really know exactly which one is driving which.”

He said that as the black hole becomes “active” and spits material out into space, “it can trigger or turn off star formations,” affecting how heavenly bodies in the path of the material evolve. Scientists believe these massive objects exist at the centre of every galaxy.

Though scientists aren’t exactly sure how the relationship between a galaxy’s dark centre and its outermost reaches works, Gallo said the new satellite can hopefully help explain.

“The galaxy dumps material onto the black hole and then at some point the black hole says, `That’s enough material, I don’t want any more,’ and it tosses it back out into the galaxy and it turns things off and stops the feeding process,” he said.

“Eventually it stops tossing material out and the galaxy starts feeding it again and you get this cyclic process.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Jan. 13, 2021.

– – –

This story was produced with the financial assistance of the Facebook and Canadian Press News Fellowship.

Comments