As the horrors of the First World War drew to a close on Nov. 11, 1918, the planet was already fighting a new, more deadly war, against an influenza pandemic that killed as many as 50 million people.

The effects of the so-called Spanish flu are thought to have shortened the war, but the virus claimed the lives of about 50,000 Canadians, many of them veterans who had survived the conflict.

Among those soldiers was the Canadian immigrant James Baird Brown, whose love for his son led to him becoming infected by the deadly flu virus.

The tragic story began in 1907 when James and his wife Ellen (née McQueen) emigrated from Scotland to Canada with their children.

They built a new life in Winnipeg, only for the outbreak of war to send three of the Browns back across the Atlantic Ocean just a few years later.

After the outbreak of war, James Jr., who was 21, and George, aged 19, enlisted with the 44th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) and fought in France.

Although George was old enough to enlist, he lied about his age, pretending he was 21, the same age as his big brother.

But what is really remarkable about the Browns is that their father, James Sr., lied about his age to enlist, too.

A few months after his sons signed up, the 53-year-old chopped 10 years off his age, to pretend he was young enough to fight with his sons.

He joined the 61st Battalion CEF and was posted to England.

“You hear about the younger (soldiers) often saying they’re older, but rarely do you hear about the older saying that they’re younger, so I guess he felt extremely patriotic,” said Canadian genealogist Eunice Robinson.

“I think the fact that he went over, because his sons were there, I think that might have just been a little icing on the cake.”

Robinson should know. Her husband Barry is the great-grandson of James Baird Brown Sr., and she has been researching the Browns’ family history, on and off, since 1973.

Get daily National news

“I believe when he finally got to England, they thought, ‘Eh, you’re too old, fella!'” said Robinson, who is a past president of the British Columbia Genealogical Society.

“So they put him to work in the quartermaster’s office, where I guess he did quite a good job.”

But like so many Canadian families in the First World War, the Browns were struck by tragedy.

On Oct. 25, 1916, George was declared missing during the infamous Battle of the Somme.

His body was later recovered and buried in a temporary war grave.

Today, George is buried at the Adanac Military Cemetery in northern France, alongside 561 other Canadians.

Records on the Canadian Great War Project website say that James Baird Brown Sr was eventually discharged for being overage, and he returned to Canada in 1917, more than a year before the war ended.

Fateful return to Europe

But in early 1919, just a few months after Armistice Day, Brown headed back to Europe again, to find George’s grave.

On his arrival in the U.K., it’s quite likely that James Sr. stayed with his son James Jr. in London.

James Jr. had married a British war bride, Eleanor Gay Masters, in January 1919, and they were living in the city’s Notting Hill neighbourhood.

It’s unknown if James Sr. got to London in time to attend the wedding, or if he made it as far as France to find George’s grave.

On March 21, 1919, James Sr. died in London, succumbing to the influenza pandemic that was sweeping the globe.

“It must have been very heartbreaking for his wife and family, to not only lose a brother but a father at the same time,” Robinson said from her home in Delta, B.C.

With the world now going through another pandemic in 2020, Robinson says it makes the events of a century ago all the more real.

“Who can envision what the world would have been like with a previous pandemic? And this has really brought it home,” she said.

“Especially with our better sanitation and our medical advice.”

The widowed Ellen Brown finally got to see her son James Jr. in 1921, when he returned to Winnipeg with his wife.

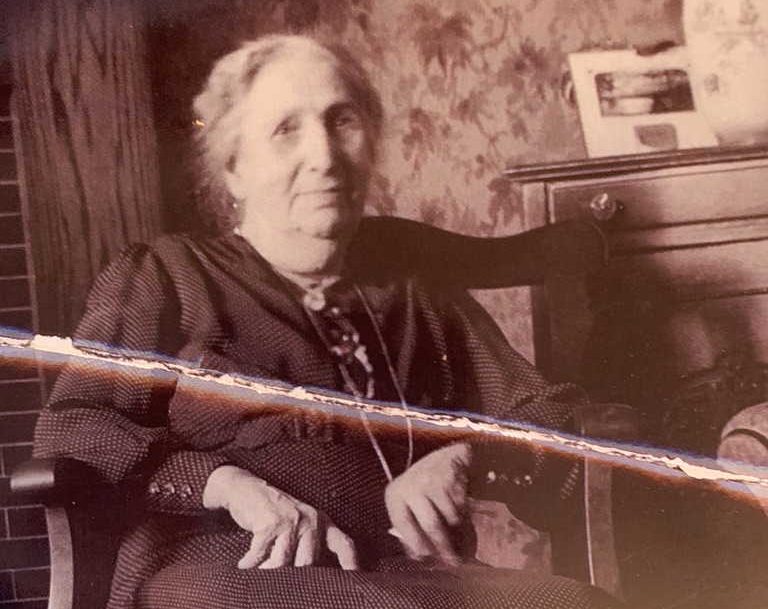

Ellen never remarried and died in 1945, aged 84.

In 1953, James Jr. died at age 60 and took with him the answer to a Brown family question that lingers to this day.

“I don’t really know if (James Sr.) ever found George’s graveyard. That was done under the Canadian War Graves Commission. So there’s a good chance that he may not have,” said Robinson.

“I don’t really know all those answers, and unfortunately, I don’t think there’s anyone living that still does.”

Whatever the answer, the Brown descendants know that James Sr. died while searching for the final resting place for his beloved son George.

Comments