The coronavirus pandemic that began as a public health crisis then metastasized into an economic crisis is likely to finish as a debt crisis that could end up swamping not only some governments but also hundreds of thousands — if not millions — of Canadian households.

The growing accumulation of debt at the household level combined with reduced incomes to service that debt — two phenomena characteristic of this pandemic — also threatens to slow the recovery.

And dealing with a future debt crisis is going to present some new challenges to policy-makers, who will have to account for one of the unique aspects of this recession: it disproportionately affects women.

“What is absolutely clear is that women have been hit harder than men in this recession. And that’s the first time ever in history because in most recessions, usually, men take it on the chin first,” said Armine Yalnizyan, an economist and Atkinson fellow on the future of workers who has, among other things, acted as an adviser to federal government departments.

Even before the pandemic, Canadian households had been taking on more and more debt. Fuelled by a long period of low interest rates, Canadians eschewed savings in favour of more spending — spending sometimes done with cash on hand but, increasingly, spending facilitated through lines of credit, credit cards or other borrowing.

The national household savings rate has been steadily drifting downward in the last decade so that, just as the pandemic hit, Canadians were saving only about $3.60 for every $100 earned.

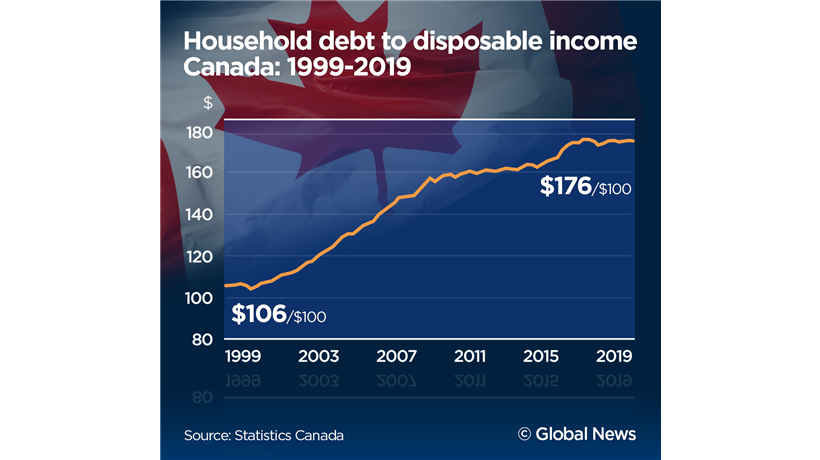

Meanwhile, the relative size of Canadian household debt has been ballooning over the last 20 years. In 1999, Canadian households had $106 of debt for every $100 of disposable income. Twenty years later, in the quarter before the pandemic, Canadian households owed $176 for every $100 of disposable income — a debt-to-income ratio of 176 per cent.

“And you’re probably going to see it at something like 230 per cent,” said Craig Alexander, chief economist at Deloitte Touche. “And the reason is that the denominator — income — will have fallen because of the employment shock that we’re having during the pandemic and the lockdown.

Get weekly money news

“Before the pandemic, Canada’s No. 1 economic risk was the amount of leverage that households had taken on the enormous amount of debt that had accumulated during an exceptionally low interest rate environment for an extended period of time.”

Canada’s big banks can see the writing on the wall. As they reported their financial statements for the first quarter of 2020, banks increased their loan loss provisions by $11 billion. That’s not to say that banks expect they will one day be forced to write off all of that, but they certainly will have to write off a portion.

And yet, as of right now, income replacement programs like the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) are, so far at least, keeping the debt wolf at the door.

“Government supports and payment deferrals for some of these debts are giving Canadians, to a certain degree, a false sense of security, which is actually allowing them to put off dealing with the debts, even though those debts may be just as bad, if not worse, when the situation ends,” said Keith Emery, CEO of the non-profit credit counselling firm Credit Canada.

But government supports are unlikely to last forever. The CERB expires after a recipient has been on it for four months, for example. And bank programs to allow mortgage holders to defer some payments only buy a few months of relief.

“The mortgage payments are going to start again,” said Alexander. “And then we’re going to find out what the real economic toll is because it’s when the mortgage deferrals end that you’re going to see whether or not there are Canadians that are having difficulty making their mortgage payments.”

The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp., the federal Crown corporation that provides mortgage insurance for most Canadian homeowners, recently told the House of Commons finance committee that it estimates 12 per cent of the country’s mortgage holders had already entered into a mortgage deferral agreement with their bank and that by September, that number could rise to 20 per cent, or one in five.

But those deferrals won’t last forever. Eventually, the bills will come due again.

“I think what we’re looking at potentially is sort of what’s being termed the deferral cliff, meaning that government supports and payment deferrals end while the economy hasn’t fully recovered, or in some cases, for personal consumers, they haven’t fully recovered,” said Emery.

Getting everyone back to work at their pre-pandemic wage levels, of course, is the best solution for all.

But as governments consider policies to reflate the economy, they will be forced to confront the gender effects of the COVID-19 recession. That means, in the first place, accounting for the decimation of the service industry — everything from salons and stylists to restaurants and tourism — an industry that has typically relied heavily on female labour.

And since the ability of many women to work depends heavily on access to child care, ensuring child-care providers are up and running becomes a critical priority if the country is to emerge from what has been dubbed the “she-cession.”

“There is no recovery without a ‘she-covery,’” said Yalnizyan. “But there is no ‘she-covery’ without child care, and we don’t have a plan for either.”

And, however you term it, there is a much slower recovery as a result of these sky-high levels of consumer debt.

“Part of the question around how strong the recovery is going to be is how are we going to power growth with that much amount of debt being carried by the economy?” said Alexander. “The consumer is 60 per cent of the Canadian economy. So if we have households with weaker finances, it could be the case that they save more.”

To economists, “saving more” is about the same as “paying down debt.” But neither paying down debt nor saving more is equivalent to spending more — which is what powers growth.

“Globally, the single biggest risk to the global economy, pre-pandemic, was the amount of leverage or debt that had been taken on. And now we’re going to have a situation that’s far worse when we get to the recovery,” said Alexander. It doesn’t mean we won’t get a recovery, but it means that this recovery could be very slow and drawn out.”

David Akin is the chief political correspondent for Global News.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.