Between the coronavirus pandemic and the attack directly preceding the worst mass murder in modern Canadian history, domestic violence — which accounts for one in five murders in Canada and kills women at a rate 4.5 times higher than men — has been thrust squarely in the spotlight.

A pandemic within a pandemic, as many have taken to writing.

Despite the attention, Dr. Kari Sampsel, an emergency room doctor and medical director of the sexual assault and partner abuse care program at the Ottawa Hospital, says there’s still a long way to go toward destigmatizing conversations about intimate partner violence. She says we need to normalize those conversations if we’re going to more effectively intervene.

“I’m trying very hard to get the word out that it’s OK to ask.”

If you’ve ever thought somebody near you was being abused but you didn’t know where to start, there are many people like Sampsel who stand ready to help.

There’s no shame in needing an assist navigating the conversation, says Karen Mason, co-founder of Supporting Survivors of Abuse and Brain Injury through Research (SOAR).

“It’s taking us a really long time to get beyond that very embedded, old-school notion that what happens in someone’s household is their own business,” Mason says.

That conversation blocker is often compounded by uncertainty over what to say, she says — an uncertainty that isn’t limited to brothers, sisters, friends or neighbours.

Lawyers, judges, doctors, nurses and other professionals need education and training, too, Mason says, because ultimately, no matter who you are or where you work, “we really need to not be bystanders. We need to care for each other.”

Domestic violence is a social problem involving whole communities, says Angela Marie MacDougall, executive director of Battered Women’s Support Services (BWSS) in B.C.

“What we tend to do is treat each of these incidents as standing alone, as individual incidents,” MacDougall says. “They are, but they are also part of the social-cultural fabric within Canadian society.”

- More than half of small businesses say U.S. no longer reliable: CFIB data

- The Bank of Canada says these are the 3 warning signs for mortgage default

- Carney says Canadian military participation in Middle East war can’t be ruled out

- Canadians want floor-crossing MPs to face ‘immediate’ byelections: poll

More people seem alert to that reality lately, she says. At BWSS, the crisis line is fielding more calls than usual from family, friends, co-workers and neighbours worried someone they know has been stuck at home indefinitely with their abuser.

Get breaking National news

If you want to broach the subject, Dalya Israel, executive director of the WAVAW Rape Crisis Centre, recommends frontloading your questions.

Say things like: “I know it can be really scary to talk about violence that you’ve experienced, but I want you to know that I’m a safe person.”

Or: “I understand that no violence is anybody’s fault, but I’d like to offer you care.”

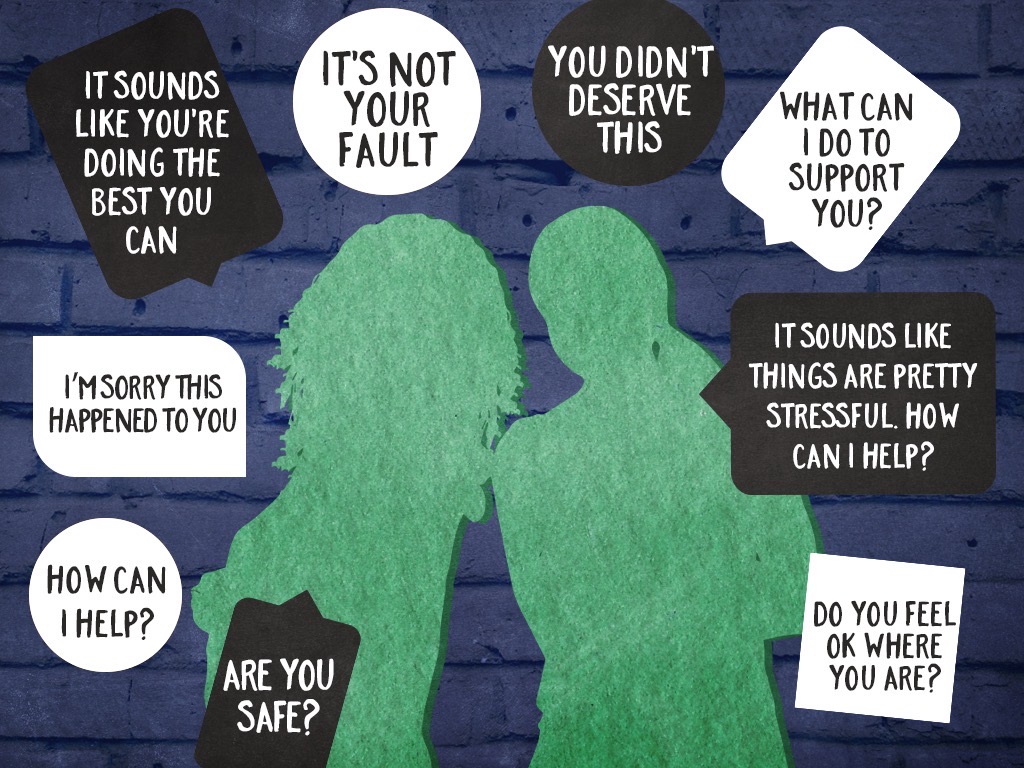

Mason recommends peppering your sentences with supportive reminders: “You didn’t deserve this,” “It’s not your fault,” “Are you safe?” or “What can I do to support you?”

Both Mason and Israel agree language is key.

“The way that somebody responds the first time that folks disclose is so crucial to the trajectory of how they will continue down the road towards healing and justice,” says Israel.

With that in mind, she says it’s best not to respond with how you “want to get this person” or commit any sort of retaliatory acts.

“Not everybody can afford to have the person who’s harming them disappear from their world,” Israel says. It could cost some people their homes, community and other social supports and even custody of their children.

Kristi Yuris, program manager at the Ending Violence Association of B.C., says the best thing you can do is make it clear your support will be ongoing.

“Survivors who are in these kinds of relationships often feel a lot of pressure from friends and family, from society, to leave,” Yuris says. But, she adds, “they might not be ready to have that conversation.”

Getting the conversation right takes time, says Sampsel — particularly in the medical setting.

“You can be ships passing in the wind, so to speak, when you’re coming back and forth from all the things you’re doing,” she says. It’s a big part of the reason why Sampsel plugs programs like her own: they’re designed for time.

In an ideal world, she says there would be “true universal screening” in health-care settings, meaning no matter what treatment a person comes in for they would be asked questions about their safety and experiences with violence as part of a medical history.

“We would pick up so many more people than we currently do because we don’t ask.”

In the legal sphere, Vicky Law says one of the reasons people don’t ask is discomfort, likely exacerbated by a lack of mandatory training.

“These issues are complex and nuanced, and it takes a nuanced approach to ask these questions and catch their red flags,” says Law, a lawyer with Rise Women’s Legal Centre.

That uncertainty over how to ask — whether to ask — is further compounded by what to do with the information when a person does disclose, Law says.

“Another reason why we don’t ask these questions is because the legal system itself is not a safe place for women to disclose violence,” she says.

In some cases, such disclosures have been met with an attack on the person’s character or accusations they’re lying, or they’re just “downright not believed.”

It’s important to remember just how expansive the issue of violence is, says Tracie Afifi, a professor at the University of Manitoba and associate editor of Child Abuse & Neglect.

“Violence against women and children is a big problem in Canada, and often people don’t realize it’s a problem here, they think maybe it’s a problem in different countries,” Afifi says.

But Canada is not immune. One in every four police-reported violent crimes is domestic violence, a woman is killed by her intimate partner on average every six days — and those are statistics that predate COVID-19.

Based on consultations with front-line providers across the country, the federal government has noted a 20 to 30 per cent average increase in demand for organizations that support victims of gender-based violence, such as shelters and crisis lines. BWSS, where MacDougall works, has reported a 400 per cent increase in calls since mid-March.

The pandemic requires Canada to innovate, says Afifi, to adjust and make sure that interventions don’t put families, already isolated because of physical distancing, at further risk for violence.

“We need to think of ways to keep people safe.”

In fall 2019, as we approached the 30th anniversary of the École Polytechnique massacre, Global News took an in-depth look at the ways in which violence against women has and hasn’t improved in the decades since.

You can find the full project here.

If you or someone you know is experiencing gender-based violence, these resources can help.

— With files from the Canadian Press

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.