Nearly three months into lockdowns and physical distancing in the time of COVID-19, it seems Canadians are still getting the message.

Recent data collected by Google provides insight into how public health measures have affected people’s behaviour. And it suggests Canadians are generally still staying home.

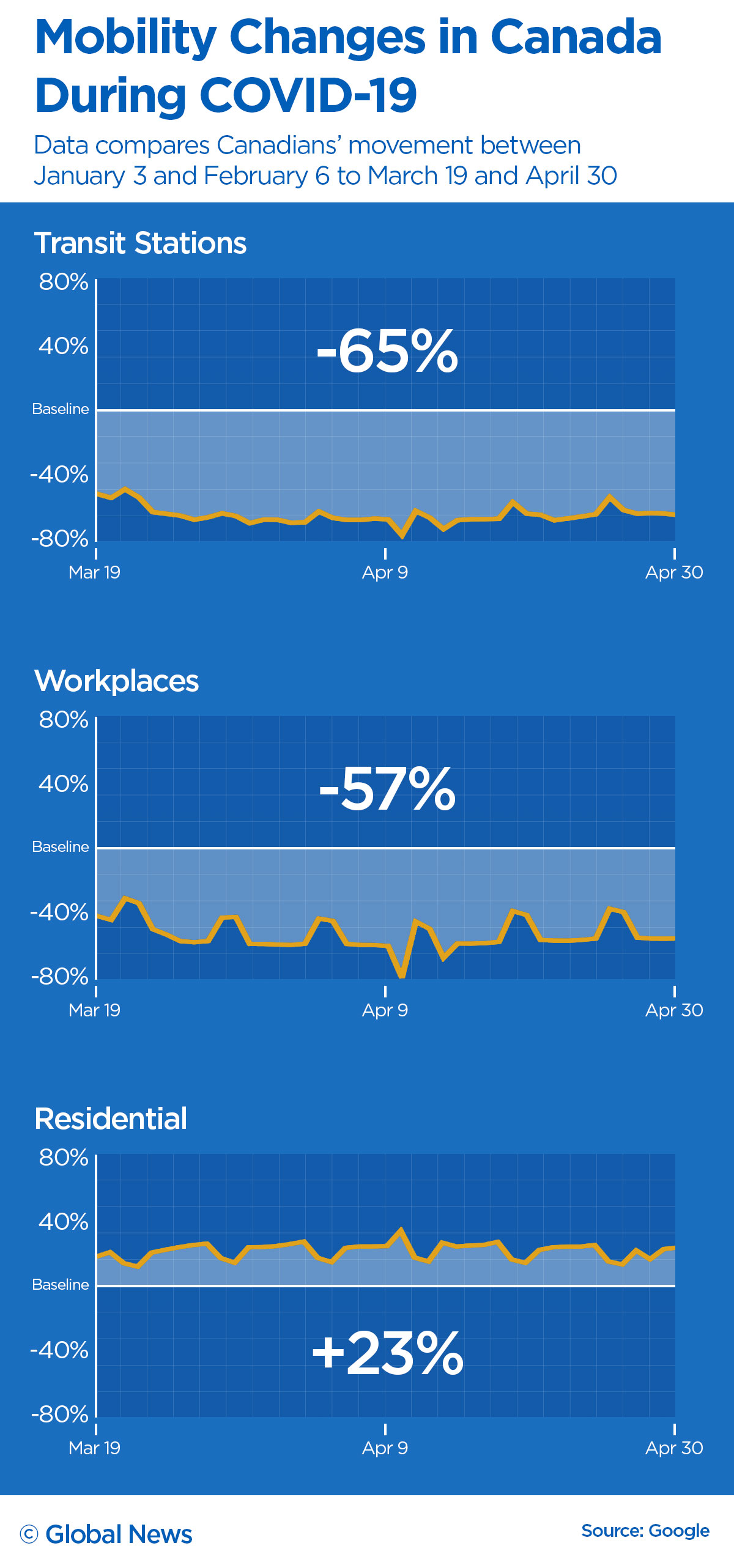

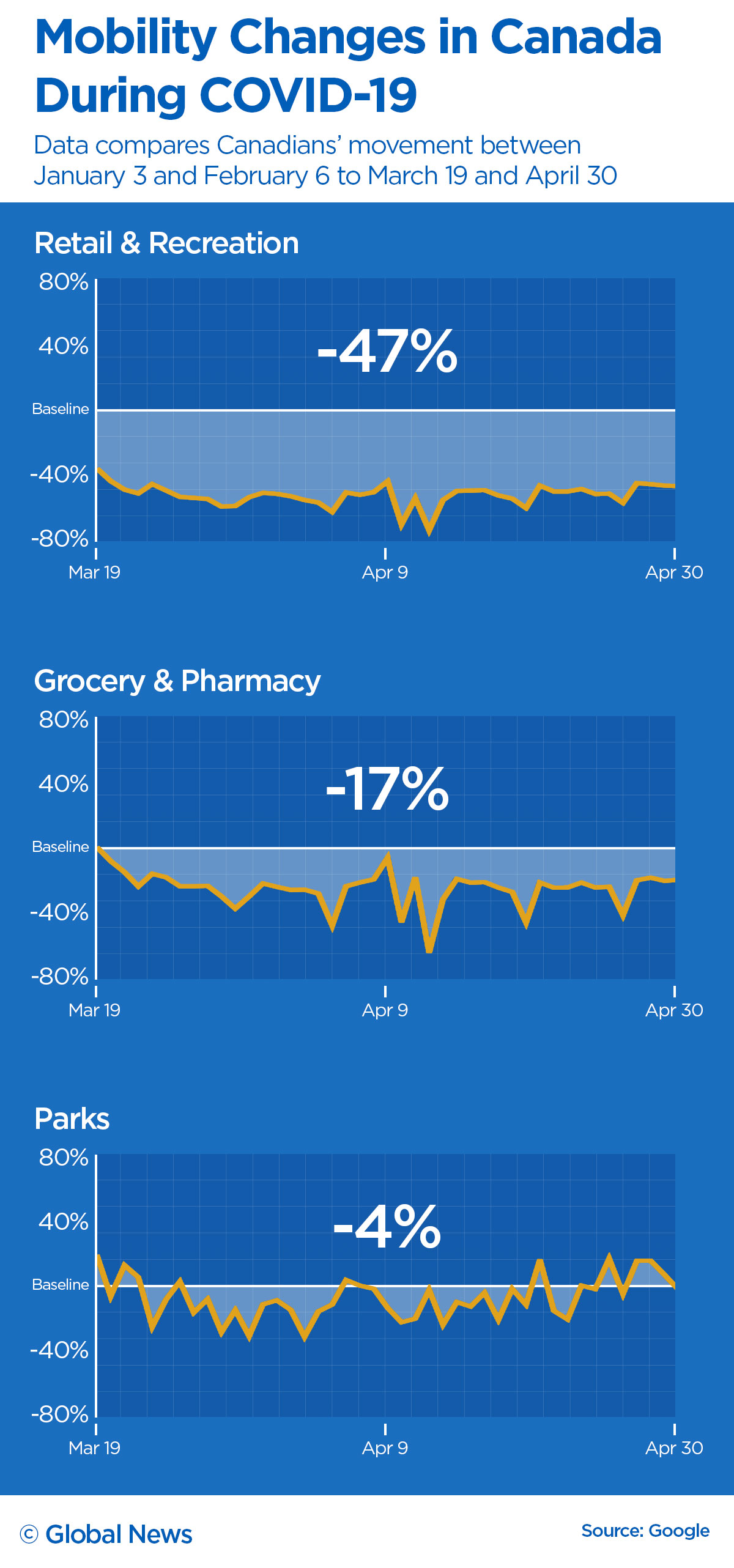

The aggregate data, posted online by Google’s Alphabet Inc. unit, shows daily traffic to retail and recreational venues, parks, transit stations, grocery stores and workplaces between March 19 and April 30 compared to a five-week period earlier this year.

Residential visits represent the only increase of the bunch — they went up by 23 per cent in Canada — perhaps signalling that the messaging is sticking as the virus lingers.

Across the country, retail visits fell about 47 per cent compared to the baseline period between Jan. 3 and Feb. 6. Workplace visits sank nearly 57 per cent in the latest period. Nationwide travel to transit hubs, including subway, bus and train stations, was down 65 per cent.

Taking a closer look at each province, the trends were mixed.

In Alberta, grocery store and pharmacy visits were down by only six per cent compared to earlier this year, while trips to retail stores dropped 40 per cent. In Ontario, trips to the grocery store were down 18 per cent, and travel to retail — i.e. shopping, cafes, libraries — was down 51 per cent.

As the weather has started to improve, many Canadians seem to be returning to parks and public spaces. British Columbia, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, New Brunswick and Newfoundland and Labrador all saw significant increases in park visits in the last five weeks. B.C. and Saskatchewan saw the biggest jumps with 65 per cent and 89 per cent increases, respectively.

Trips to transit stations were significantly down across the provinces — 67 per cent in Ontario, 56 per cent in B.C. and 73 per cent in Quebec.

Get weekly health news

For all, there was an increase in at-home life, with positive figures ranging between 15 and 26 per cent.

The data runs in lockstep with the breadth of orders imposed by governments over the past few months.

Canadians first heard the “stay-at-home” message in mid-March, and it only intensified as the month went on. Every province and territory declared a state of emergency, ordering closures of non-essential businesses and urging citizens to distance from others. While some provinces have begun relaxing restrictions, the orders lifted so far have been relatively small and began slightly after the five-week period Google’s recent data reflects.

Google says it started providing these reports in an effort to assist governments and researchers with ensuring residents are remaining in their homes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

While the technology is nothing new, privacy experts have been wary about its use on such a large scale — especially if it’s being used by governments.

“History shows us governments, when they take on emergency powers during a crisis, don’t generally give those powers back,” said David Shipley, CEO of Beauceron Security, a New Brunswick-based firm that specializes in helping businesses become and remain secure online.

Google’s data is derived from users who have enabled the “Location History” feature on their phones. The company claims it has weaved in technical measures so no individual can be identified through the reports.

But there are still risks — aggregate data or not — according to Kerry Bowman, a professor of bioethics and global health at the University of Toronto.

“A lot of people think that if it can’t be traced to an individual, as long as it’s aggregate data, it’s not worth discussing. I’m not convinced that’s true,” he said.

Unless these technologies prove “profoundly necessary” to the epidemiology of the pandemic, it’s otherwise “hard to justify,” he said.

He believes it may be building habits with Canadians now that will be difficult to roll back later.

“The risk with this is that these inroads into privacy will have been made, and they may not be rolled back. The public tolerance of this will be shifted,” he said.

“As an ethicist, I’d say the time to really hang onto core beliefs and core values is during an emergency… In Canada, privacy is a democratic principle, so I worry we may become desensitized to this.”

Shipley said that while these tools can certainly help local governments get a better idea of whether public health measures are being observed, the technology isn’t foolproof and it runs the risk of being inaccurate.

“The data accuracy of location data depends on the qualify of the measurement,” he told Global News in a previous interview. “If you’re a person living in an urban area in Atlantic Canada like Halifax and you’re close to your WiFi and other data points, the more accurate it is.

“But if you’re living in rural Atlantic Canada and you only have the cellphone signal, for example, maybe not the GPS data, it can be as inaccurate as a couple of kilometres.”

Contact tracing, which involves retracing the steps of a COVID-19 patient and tracking down their recent contacts, has similarly drawn privacy concerns.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has said that Ottawa is looking into the potential of using smartphone apps to digitally trace contacts of identified coronavirus cases but that such an app should be voluntary to earn public support. The country’s chief public health officer said that while contact tracing could be beneficial to stop the spread, the technology itself remains unproven.

Canada’s top privacy commissioner told Global News that the app — should it come into play — needs to be designed properly and meet a series of criteria to balance privacy concerns with public health needs. A recent statement from federal and provincial privacy commissioners warns against going ahead with said apps until certain criteria are met.

Bowman said contact tracing is even more worrisome.

“There’s an erosion of some basic principles in society in term of personal liberty,” he said. “If all these things come into play, how are we going to get that privacy back?

— With files from the Canadian Press, Reuters and Global News’ Jeremy Keefe

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.