A significant number of Saskatchewan veterinarians have been silent in the face of suspected animal abuse, according to a survey from the province’s regulator for vets.

About 77 per cent of vets and veterinary technicians have suspected animal cruelty, according to the Saskatchewan Veterinary Medical Association (SVMA) survey released in January. About 15 per cent said it’s possible they’ve encountered an abused animal.

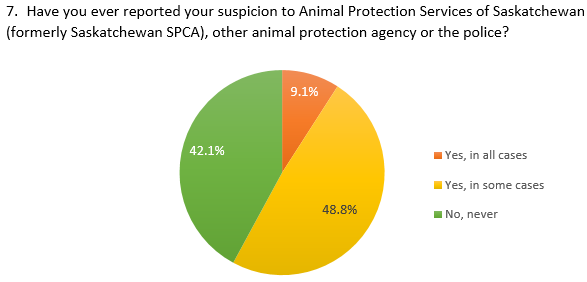

Despite the vast majority of animal health-care workers having suspected abuse, survey results show only 58 per cent have reported a suspicion to an animal protection agency.

Saskatchewan’s Animal Protection Act was updated in 2018 to make it mandatory for veterinarians to report suspected cruelty. About 12 per cent of survey respondents were not aware of the change in legislation.

The SVMA survey highlighted several reasons why vets and techs haven’t reported suspected cruelty, including fear of repercussions on their clinics, uncertainty about whether an animal was abused and discouragement from employers.

Get daily National news

Woodsworth said she regrets failing to report animal cruelty early in her 12-year career.

“It was our ethical obligation,” she said.

“I wish that I’d been in a situation where I felt more confident to stand behind what I felt my professional ethics were telling me to do, as opposed to … what might have been most comfortable for the folks who were managing and running the practices I worked for.”

Vets worry reporting a suspicion could garner negative attention from the community or take a toll on their practices’ bottom line, according to the survey.

Woodsworth said veterinarians can fall back on their professional ethics and the Animal Protection Act.

“If you’re reporting something in good faith, particularly when your professional bylaws and when the legislation in the province tells you you must as a professional… no judge is going to say you did something wrong,” she said.

For many animal health-care professionals, the investigation process is shrouded with uncertainty. Fifty-seven per cent of survey respondents said they don’t feel confident in their understanding of the process.

Many worry it will take a toll on their clients, Woodsworth said.

“Veterinarians are afraid of reporting. They’re afraid of what might happen to the people at the end of the day,” she said, highlighting the potential trauma associated with having a pet seized by animal protection services.

Dennis Will, the chair of the SVMA’s animal welfare committee, noted prosecution is rare. The SVMA says 98 per cent of investigations are dealt with through education and compliance checks.

The SVMA is working hard to clear up any questions animal health-care workers have about the reporting and investigation processes.

The association started hosting continuing education sessions across Saskatchewan prior to the 2018 amendment to the Animal Protection Act.

“If we can raise awareness, then there will be less animals that will be treated inhumanely and … there will be more cases coming forward,” Wills said.

“I’m very hopeful for the future.”

Woodsworth said during vet school, she didn’t receive any formal training on identifying or reporting animal cruelty. Now, the Western College of Veterinary Medicine is updating its curriculum to improve animal welfare education.

“That’s going to be a good way to kind of get people … more comfortable with the idea of reporting and more comfortable with what happens when a report is made,” she said, “and that … you’re not really kicking your clients in the butt and that it’s not going to ruin your bottom line.”

The survey results, as published by the SVMA, did not contain information about the methodology or margin of error or equivalent. The SVMA said roughly 150 veterinarians and technicians took part in the survey.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.