George Iny recalled a woman who wrote in saying she was paying around $550 a month for her new 2018 Toyota Corolla on a seven-year loan.

“She doesn’t appear as anybody’s statistic anywhere, but obviously her household suffers because she’s paying $250 a month too much for that car,” reckoned Iny, who heads the Automobile Protection Agency (APA), a consumer advocacy group.

Perhaps the most egregious example he’s ever seen of an inflated auto loan is that of a man who owed almost $100,000 on a Chevrolet Volt, an electric car.

“We see people like this, not every day, but every week for sure.”

Behind the gargantuan loans are ever longer auto loans, early trade-ins, and negative equity, an issue that’s been long known to insiders but remains poorly understood by many consumers, according to Iny.

Negative equity

What is “negative equity?” you may wonder.

It means the market value of whatever you bought has fallen below the outstanding balance on the loan you took out to purchase it.

In real estate, this is known as “being underwater” and is a relatively rare occurrence. Home prices generally rise year over year so it usually takes a housing downturn for homeowners to find themselves underwater (think of what happened in the U.S. after the 2007 housing bust). Negative equity on a house can be a headache because, in a recession, it may force you to stay put in an area where there are no jobs instead of moving to where there are more opportunities. You’re stuck because you’d lose money — potentially lots of it — if you sold the house.

READ MORE: How to buy a car without getting swindled

For cars, though, it’s different. Unlike houses, vehicles typically lose value over time, meaning that, unless you’ve made a large down payment, you’ll probably owe more on your new car than the vehicle is worth, at least initially.

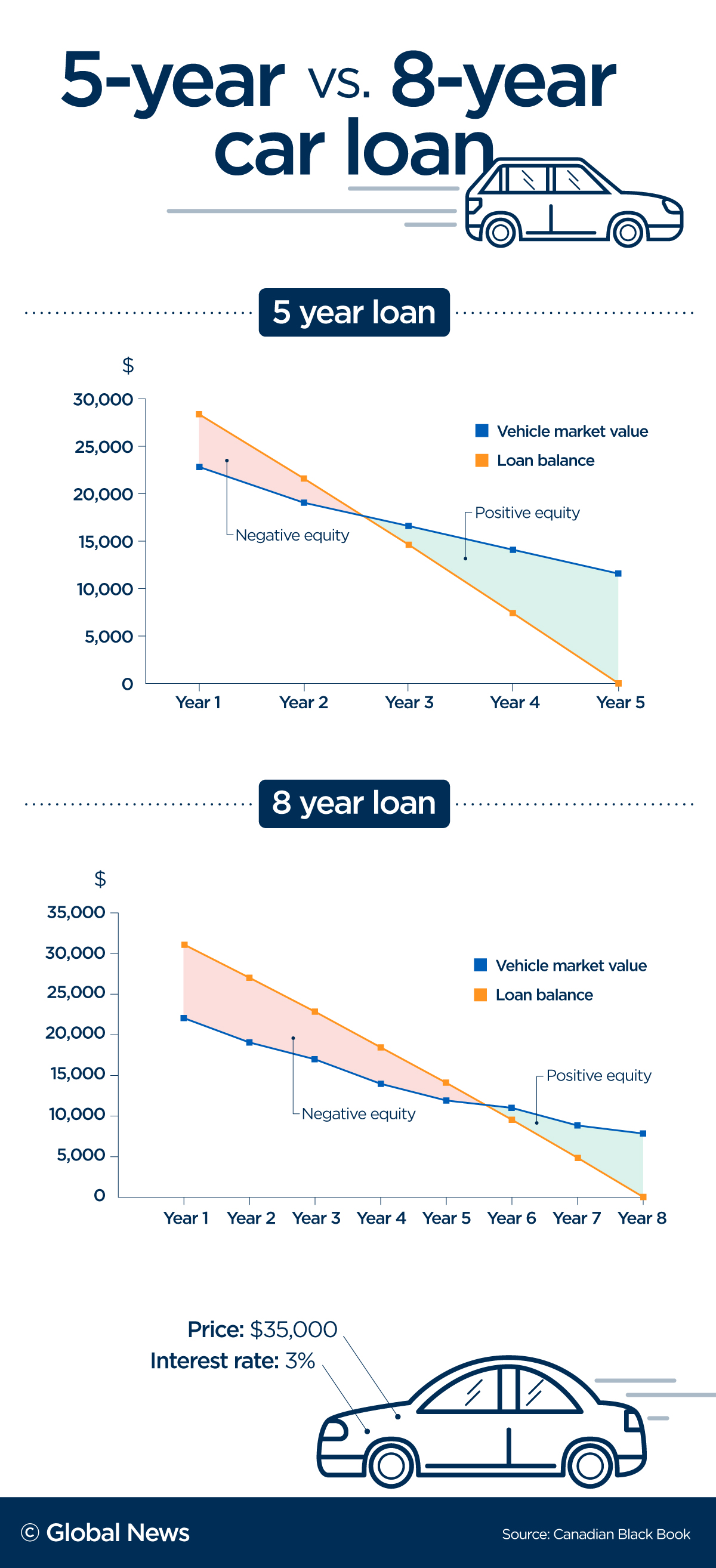

Vehicles generally lose about one-third of their value in the first year of ownership, said Brian Murphy, vice-president of data and analytics at Canadian Black Book. The good news is the pace at which vehicles lose value slows down considerably after the first year. Since the pace of your auto-loan repayments remains constant, that means you’ll eventually catch up and start to owe less than your four-wheeler is worth, something known as positive equity.

However, the smaller your down payment — if any — and the longer your loan term, the more it’s going to take you to get there.

The problem with negative equity arises when you trade in your vehicle before it’s fully paid off, something that’s become increasingly common among car buyers in Canada.

Let’s say you bought a $35,000 compact SUV with an eight-year loan and zero down. It might take you a whopping six years to reach the point at which your vehicle is worth more than the balance you owe on it. If you decided to trade it in after three years, for example, you’d still be $5,800 in the red, according to an example provided by Canadian Black Book.

Now let’s pretend you’ve set your eyes on a new $40,000 vehicle. In order to finance that, the lender would fold your old $5,800 balance into the new loan, for a total debt of $45,800.

If you started out with a shorter loan but still traded in with negative equity, your lender may be able to keep your debt payments roughly steady by offering a longer loan, Iny said. While the impact on your cash-flow may be minimal, your debt load is mounting.

READ MORE: Three numbers you should check before deciding whether to lease or buy a car

That’s how cars are getting Canadians into a spiralling cycle of debt, according to Iny.

“Eventually, you’ll be asking for a loan that is too big compared to the asset that you’re buying,” Murphy said.

And that, he added, is when the bank will say “no.”

The financial crisis, low-interest rates and aggressive marketing

Borrowing to buy a car wasn’t this treacherous when the longest auto loan you could get was five years, Iny said. The trouble started after the financial crisis of 2008, when many vehicle manufacturers started offering terms of up to eight years.

Amid a weak economy and stalling sales, “the feeling was if they could keep the payment low enough in a low-interest-rate environment, they would be able to bring people in the door,” Iny said.

The strategy worked, and the sector bounced back after a couple of years, Iny recalled.

READ MORE: Electric car incentives in Canada — what to know about the rebate that includes Tesla 3

But the industry quickly realized seven or eight years was too long to see customers again. The solution, according to Iny, was to get car owners to trade in their vehicles before the loan term was up — with the outstanding loan balance folded into the new loan.

To lure customers back in, the industry often resorts to aggressive marketing campaigns, according to Iny. Often, this involves a mailed invitation to come check out the new models.

“It’s like wine and cheese — something like a fancy museum opening atmosphere,” Iny said. “But (they’ll) tell you, ‘Listen, for the same payment, we could get you into a new car. Why would you want to keep this old one? You get the Bluetooth, you’ll get the backup camera’.”

For many, he said, the offer is “pretty irresistible.”

But are longer auto loans necessarily bad?

If you don’t trade in your vehicle with negative equity, a longer-term loan can be a good deal.

With a zero per cent interest rate, a longer loan simply means lower monthly payments, theoretically freeing up money you could invest and earn a return on.

For anything above a zero per cent rate, you’ll want to look at how much more you’d be paying in interest overall with a longer loan. But if the interest rate is low, it might still make sense to opt for lower payments.

Those are the “thoughtful” arguments Iny said he’s heard from financial planners.

In practice, though, he said, many people aren’t going to invest a small amount of money they may save through a smaller auto-loan installment. They’ll just use longer loan terms to keep their payments steady and buy more expensive cars.

READ MORE: Own a car? You won’t believe how much that’s costing you every year

Still, one way to avoid negative equity, even with a longer loan, is to choose a vehicle that will better retain its value, Murphy said.

With a Toyota 4Runner, for example, someone with a $54,000, seven-year loan would reach positive equity after just four years, because the mid-size SUV depreciates remarkably slowly, he added.

In notes provided to Global News, Murphy compared the 4Runner to an unidentified similar vehicle that had a slightly lower price tag but a worse record of retaining its value. Someone with a $52,000, seven-year loan for this SUV would have to wait almost six years to be able to trade it in without negative equity.

To help consumers evaluate their negative-equity risk, Black Book provides yearly rankings of four-year-old models with the best-retained values. It also has an online loan-equity calculator.

Still, longer loans come with greater risks even if you chose a vehicle that will depreciate slowly or you don’t plan to trade in early, Murphy warned.

Take car accidents, for example.

“If your car gets written off and your insurance company says your car is worth $20,000, but you still owe $30,000 on (it), you can guess whose responsibility the difference might be.”

The longer it takes you to reach positive equity, the greater the risk you might find yourself on the hook for the balance owing on a vehicle that’s declared a total loss due to either an accident or theft.

Some insurance policies offer the option to buy extra coverage to avoid this, said Anne Marie Thomas of InsuranceHotline.com. However, that usually only extends to the first two years after the purchase.

Beyond that, there’s so-called gap insurance, which will cover all or part of your negative equity for a few more years, Thomas said.

Gap insurance may be worth it, Thomas said. But it’s still an additional cost tied to your decision to buy a vehicle with little or nothing down and a longer loan term.

The crux of the problem, according to Iny, is that lenders are now making auto loans worth far more than the market value of the vehicle they’re meant to finance.

While car loans are often slightly more than the vehicle’s price because they may also cover things like taxes and an extended warranty, until about 20 years ago, the maximum anyone would lend was 110 per cent of market value, according to Iny. On a $20,000 car, that would work out to $22,000.

Today, Iny said, “some … will allow you to finance up to $30,000 or $31,000.”

Comments