Bots have represented about five per cent of social media activity during the election, according to a study by the Ipsos Canadian Political Atlas.

That’s far behind regular users (63 per cent) and influencers (25 per cent).

“It is a bit early to tell, but early indications are that they’re not playing a major role in the campaign,” says Gregory Jack, a vice-president at Ipsos. “I think we’ll know better after the campaign is over, unfortunately.”

Ipsos classifies an account as a bot if it seemed to be outside Canada and was claiming to be inside Canada, “makes strange spelling mistakes,” or is active at unlikely times of the day,

“Accounts with very few followers that just came online, accounts that rapidly tweet out new tweets much more quickly than an individual could, especially if that account is claiming to be an average voter in Canada,” Jack explains.

The largest single category of bot activity was negative comment about the Liberals, followed by negative comment about the Conservatives, Ipsos found.

It’s not clear how the five per cent figure compares to the 2016 U.S. election or the Brexit campaign in the U.K., Jack said.

Get breaking National news

It’s hard to tell where the accounts originate or who could be operating them.

A small number of inauthentic accounts still have the potential to distort debate, Jack says.

“Even though we only see five per cent activity, what can happen is that it can get out in the social media space, and a real user might see it, pick up and redistribute that information, and if it’s not true, you’re creating a cascading effect around some of these accusations or tactics that they might be using.”

Ipsos looked mostly at Facebook, but also at Twitter and Instagram.

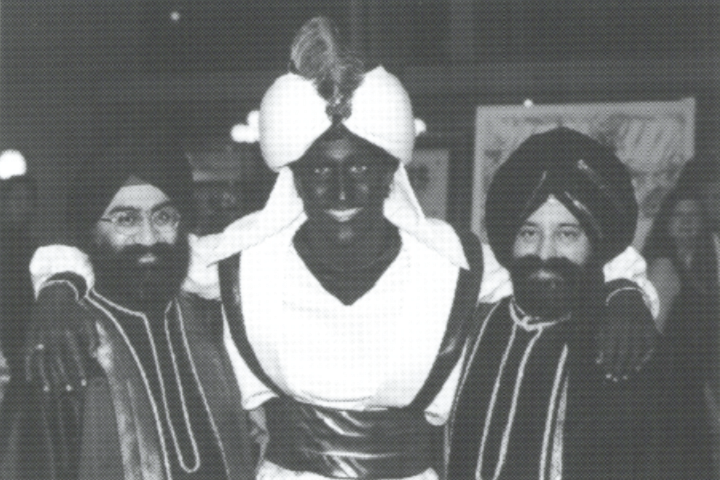

A blackface/brownface scandal involving Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau came and went last month without attracting online disinformation, a separate study released on Thursday found.

Hashtags related to the controversy had about a three-day cycle starting on Sept. 19, according to the research.

Twitter engagement with the hashtags was strong, especially among Conservative and People’s Party of Canada supporters. However, people using the hashtags largely linked to mainstream Canadian news outlets, plus Time magazine, which broke the original story.

The popularity of the hashtags also seemed to be driven by real users and not bots, according to the study.

“It does not appear that the immediate popularity of these hashtags was driven by what is increasingly called ‘co-ordinated inauthentic behaviour,'” the authors wrote.

The report was released by the Digital Democracy Project, which is led by the Ottawa-based Public Policy Forum and McGill University.

Its findings confirm research by Storyful, a Dublin-based online analysis company, which said in late September that it had not identified “a network of bot-like or suspicious accounts amplifying the Trudeau-brownface/blackface story.”

“We’ve run a number of searches across mainstream and fringe platforms and analyzed the accounts posting about the topic, but so far, what we’re seeing tallies with a widespread, organic-looking discussion of the story,” head of news intelligence Padraic Ryan wrote in an analysis for Global News.

Photos and videos of the Liberal leader in costumes including black or brown makeup came to light in mid-September. The images were taken as recently as 2001.

Trudeau apologized after the images were made public, but he has been noncommittal about how many more similar images may exist.

In early October, researchers from Harvard University said the blackface/brownface story “has created an information environment ripe for exploitation by partisans and other bad actors seeking to spread confusion, division and hate.”

“Trudeau, by failing to rule out other blackface instances, has created uncertainty about whether new photos will emerge,” the authors wrote. “For motivated political opponents, these moments of uncertainty provide great opportunity for the creation of hoaxes.”

Online disinformation campaigns targeted the U.S. 2016 election, the Brexit referendum debate in the U.K. and recent elections in several European countries. But so far, such campaigns don’t seem to be a significant factor in Canada’s federal election.

— With files from the Canadian Press

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.