A union certification vote is underway for Foodora couriers in Toronto to decide whether they’d like to join the Canadian Union of Postal Workers (CUPW), and with similar pushes in Canada and beyond, an employment lawyer calls this a potential watershed moment.

CUPW said if the union certification goes ahead for the food delivery workers, it would create Canada’s first certified bargaining unit for app-based workers.

Paul Willetts, a labour and employment lawyer, said the fight is very significant — and comes down to whether the workers are classified as employees under Ontario law, which affords them protections such as guaranteed minimum wage, paid vacations and leaves.

“All those protections provide you with certainty, with stability and with an ability to plan your life. So I think that’s one of the things that’s missing for people working in the gig economy, and why it’s more precarious,” Willetts said.

“The flip side of that coin is it places additional obligations on the companies now found to be employers, and the implications of that could mean significant costs.”

- Stock markets plummet as oil nears $90 amid Iran war, U.S. job losses

- ‘A foreign policy based on short memory’: Carney continues push to diversify from the U.S.

- Americans view each other as morally bad, poll says. Canada is the opposite

- Canada and Japan sign partnership deal on defence, energy, trade

Ivan Ostos has been a bike courier with Foodora for three years. He said his work involves a schedule that isn’t stable, working outdoors in what can often be harsh conditions, and being a target for thieves.

“Any delivery person has a fear of getting robbed when they’re in the city like this because people know we’re carrying food. Often times, we can fall victim to that as well as getting our bike stolen,” Ostos said.

READ MORE: ‘What other industry would allow that?’ — What it’s like to work for service apps

As for pay, Ostos said the company gets 30 per cent of the revenue that customers pay the restaurants, while couriers get only a $4.50 delivery fee paid by the customer plus potential tips, and $1 per kilometre travelled between restaurant and customer paid by Foodora.

“We have no say right now,” he said, explaining his desire to unionize.

“Wage is definitely a top issue, as well as respect. Because frankly, the way we’re treated on a daily basis by this company is really abhorrent. We’re not allowed to go into the office to answer our questions whenever we please. Meanwhile, they say they have an ‘open-door policy.’ They have a lock on the door,” Ostos said.

Get breaking National news

Foodora Canada declined an interview with Global News. Managing director David Albert mentioned in an emailed statement that it has an open-door policy, but said it’s not possible to address “every single complaint from thousands of couriers.”

“We’re a growing player in a highly competitive new service industry in Canada. We don’t believe that our couriers need a union to affect change,” Albert wrote.

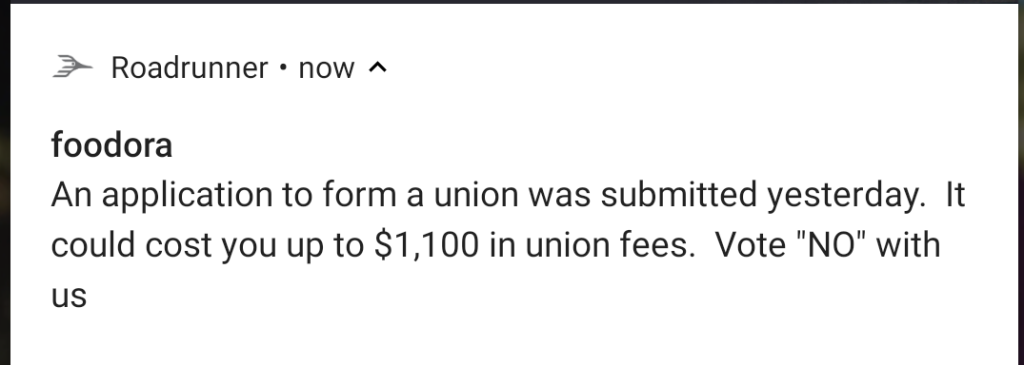

During this fight, CUPW has launched a complaint with the Ontario Labour Relations Board, accusing Foodora of spreading “lies and misinformation,” and scaring workers into voting against unionization by threatening their income.

The company has been sending emails and push notifications through its app for workers. One obtained by Global News reads, “It could cost you up to $1,100 in union fees. Vote “NO” with us.”

Willett said that when exploring unionization, both sides have a right to share information about what’s going on.

“But that doesn’t mean that they can get into things such as fear-mongering, scare tactics, placing undue pressure on individuals to try to influence the process,” Willett said.

Albert said the company has always acted legally and in good faith.

“We cannot and have not made promises about future changes or improvements to the workplace, nor have we threatened loss of job or income. The union, however, can make any promise it wants, regardless of its ability to deliver on such promises,” he wrote.

While Foodora workers could become the first of the gig economy to unionize in Canada, they’re not the only ones.

Hundreds of Uber drivers in Ontario and western Canada have signed up with the United Food and Commercial Workers union (UFCW Canada). The union is currently sorting through all the signed cards, figuring out exactly where to apply for bargaining unit certification.

WATCH: Hundreds of GTA Uber drivers join union

And the workforce is changing so much that last year UFCW created a new role to keep pace. Pablo Godoy is the national coordinator for gig and platform initiatives. He said working with Uber drivers is the first project.

“We’ve been seeing an onslaught of new forms of employment in these industries. Specifically, platform employers or app-based employers that are accessing or sourcing labour in a way that we haven’t seen before,” Godoy said.

“At a push of a button, employers are having access to workers, but by way of using these technologies, they’re able to circumvent traditional labour laws that have been set up for decades upon decades to protect workers so that they have the most basic minimum rules and regulations in the workplace.”

Godoy said technology and innovation is changing things fast — and food retail is a good example.

“Jobs aren’t necessarily disappearing. They’re just changing.”

READ MORE: The gig economy is making cash flow management a nearly impossible task

At the same time, Uber workers in Ontario have launched a class action lawsuit, alleging they should be treated as employees, which affects the tens of thousands of people who’ve been driving for the company since 2012.

This spring, the Supreme Court of Canada announced it would hear an appeal about part of the case regarding the arbitration clause in worker contracts.

WATCH: Protesting Uber and Lyft drivers take to the streets in NYC

“I think we’re going to see this play out over the next several years. … I don’t think the Foodora issue will be an easy fight,” Willetts said.

“It’s a struggle right now … and part of the problem is there’s a gap between technological advancement and type of work that’s being made available, and the law trying to catch up,” Willetts said.

It’s a struggle that he believes will take several years to play out — and that one those working in the gig economy should watch closely.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.